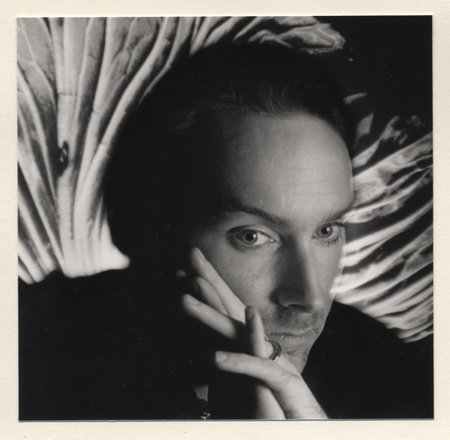

Dale E. Basye

The idea for Heck: Where the Bad Kids Go came to me where most of my ideas come from: that area just behind the eyes and somewhere, approximately, between the ears. A friend of mine, whom I’ll refer to as “Paul Harrod,” wanted to make a short “mockumentary” film on the devil, sort of a VH1 “Behind the Brimstone”-type of thing (sorry for all the quotes and the parenthetical asides). While helping him to mine the topic for potential nuggets of humor, I unearthed the idea of an H-E-double-hockey-sticks Lite, just for children, which–of course–simply had to be called Heck. I researched such classic works as Dante’s Inferno and the phonebook (I wanted a pizza) and came up with a kid-ified underworld specifically designed to ignore the needs and enflame the misery of once-living children everywhere–in particular, the bad ones.

Of course, every story needs what is commonly referred to as a protagonist. That is, a hero, or–at the very least–someone whom the reader can relate to in some way while serving as a guide through a host of unpleasant, fantastical circumstances. Often, the protagonist mirrors the author, not for any significant reason other than it’s much easier for the author (fewer things to make up) while giving him/her the perfect excuse to write about himself/herself. Ever the overachiever, I decided to have two protagonists–hardly a “novel” idea–but it allowed me to write through my dual selves–the ever cautious, perpetually in-his-head Milton, and the tart, impulse-control-challenged Marlo.

Now it was just a matter of writing it all down. Oh, yes…writing…

Writing is really, really, really hard. It’s easier if you have fingers and not, say, great unwieldy crab claws, but still. There are only two enjoyable aspects of the writing experience, as I see it. The first is when you are on the bus, clipping your toenails, or grooming the pet monkey you “found” at the circus: those little in-between moments where inspiration often bubbles to the top of your consciousness like a cork bobbing up to the surface of the sea. It’s when you come up with that big idea…the one that seems so inevitable, as if it had always been there, only you were the one to stumble on to it. You’re elated. You’re filled with excitement. You miss your stop, cut your pinky toenail too deep, or accidentally tug too hard on your monkey’s fur with its brush (which Dr. Zaius hates…I have the bite marks to prove it). It’s a great moment (not the monkey bites, but the “zapped with creative fire” part). Unfortunately, when a writer is blessed with a good idea, he/she is then immediately cursed with having to actually do something about it. This is called work. Some writers also consider this play, but–to the best of my knowledge–Roget’s Thesaurus doesn’t happen to include “play” as a synonym for “work.”

The second great part of writing is right after you are through and are fairly convinced that what you wrote isn't completely awful. Not that you ever really think that (or that you are ever really “through”) but there’s a point where most of the heavy lifting is done and the voices in your head at least dull to a manageable murmur. This is also the point where it is safe for your family to come out from underneath the kitchen table, bearing soap, a towel, and a change of clothes.

So why write? There are some who write solely to pay the utility bill, to which I say: good luck. Then, there are others, who simply have to write. This is the column I find myself squarely in. I’ve tried to express myself eloquently with guitar solos, touchdowns, and even ballroom dancing once, and the only thing I managed to achieve was a state of humiliation (and occasionally sore feet). Writing is the closest I’ve come to putting something out in the world that bears a faint resemblance to the notion that was originally in my head (this essay notwithstanding).

And, somehow, it’s all worth it. The staring at the screen until it stares back. The slow dwindling of friends, hairs, and social niceties. The less-than-healthful food choices. The getting up in the middle of the night and splashing in your neighbor's koi pond (this may not have anything to do with writing but may instead be a symptom of a deeper problem). But when you go to a bookstore and see your book, or even simply the space where your book will soon be, you feel as if you have joined an illustrious fraternity of literature, a centuries-old club boasting everyone from Aesop to Zola (a French writer whom one should only read if one finds oneself unbearably happy and wishes to remedy this condition immediately).

Speaking of tedium, I couldn’t stand school. And the feeling was mutual.

But, thanks to some phenomenal teachers, I realized the freeing power of the imagination. It was as if every story I wrote or doodle I scrawled was a spadeful of dirt, unearthing a secret tunnel, getting me closer and closer to escape. Laughter was also a lifesaver for me, often literally. Not only is it rightfully considered the best medicine (if used liberally, only as directed), it can also save you from getting your butt kicked in PE.

The point is (yes, there's a point here somewhere), that preadolescence can feel like an eternity when you’re in it, but you actually get through it fairly unscathed, though your body and voice may soon be rendered unrecognizable. This complete freakishness is normal. So let laughter and perseverance be your best and most trusted bodyguards, providing loyal service without even demanding your lunch money in return.

I hope that you enjoy, appreciate, and–above all–buy my book Heck: Where the Bad Kids Go–at least three copies (one for locking away in your safe for future generations, one for reading, and one for travel). I think you’ll find that it’s a story full of laughter and hope (OK, and a fair amount of demons, poop, and dead historical figures). And if you don’t buy it for the story, then buy it for the amazing illustrations by Bob Dob. So, thank you for reading this long-winded essay (assuming you still are) and I caution you to be wary of words such as flummox, maelstrom, and irony. If you find yourself using them, you may already be a–egads–writer.

Cordially,

Dale E. Basye

Of course, every story needs what is commonly referred to as a protagonist. That is, a hero, or–at the very least–someone whom the reader can relate to in some way while serving as a guide through a host of unpleasant, fantastical circumstances. Often, the protagonist mirrors the author, not for any significant reason other than it’s much easier for the author (fewer things to make up) while giving him/her the perfect excuse to write about himself/herself. Ever the overachiever, I decided to have two protagonists–hardly a “novel” idea–but it allowed me to write through my dual selves–the ever cautious, perpetually in-his-head Milton, and the tart, impulse-control-challenged Marlo.

Now it was just a matter of writing it all down. Oh, yes…writing…

Writing is really, really, really hard. It’s easier if you have fingers and not, say, great unwieldy crab claws, but still. There are only two enjoyable aspects of the writing experience, as I see it. The first is when you are on the bus, clipping your toenails, or grooming the pet monkey you “found” at the circus: those little in-between moments where inspiration often bubbles to the top of your consciousness like a cork bobbing up to the surface of the sea. It’s when you come up with that big idea…the one that seems so inevitable, as if it had always been there, only you were the one to stumble on to it. You’re elated. You’re filled with excitement. You miss your stop, cut your pinky toenail too deep, or accidentally tug too hard on your monkey’s fur with its brush (which Dr. Zaius hates…I have the bite marks to prove it). It’s a great moment (not the monkey bites, but the “zapped with creative fire” part). Unfortunately, when a writer is blessed with a good idea, he/she is then immediately cursed with having to actually do something about it. This is called work. Some writers also consider this play, but–to the best of my knowledge–Roget’s Thesaurus doesn’t happen to include “play” as a synonym for “work.”

The second great part of writing is right after you are through and are fairly convinced that what you wrote isn't completely awful. Not that you ever really think that (or that you are ever really “through”) but there’s a point where most of the heavy lifting is done and the voices in your head at least dull to a manageable murmur. This is also the point where it is safe for your family to come out from underneath the kitchen table, bearing soap, a towel, and a change of clothes.

So why write? There are some who write solely to pay the utility bill, to which I say: good luck. Then, there are others, who simply have to write. This is the column I find myself squarely in. I’ve tried to express myself eloquently with guitar solos, touchdowns, and even ballroom dancing once, and the only thing I managed to achieve was a state of humiliation (and occasionally sore feet). Writing is the closest I’ve come to putting something out in the world that bears a faint resemblance to the notion that was originally in my head (this essay notwithstanding).

And, somehow, it’s all worth it. The staring at the screen until it stares back. The slow dwindling of friends, hairs, and social niceties. The less-than-healthful food choices. The getting up in the middle of the night and splashing in your neighbor's koi pond (this may not have anything to do with writing but may instead be a symptom of a deeper problem). But when you go to a bookstore and see your book, or even simply the space where your book will soon be, you feel as if you have joined an illustrious fraternity of literature, a centuries-old club boasting everyone from Aesop to Zola (a French writer whom one should only read if one finds oneself unbearably happy and wishes to remedy this condition immediately).

Speaking of tedium, I couldn’t stand school. And the feeling was mutual.

But, thanks to some phenomenal teachers, I realized the freeing power of the imagination. It was as if every story I wrote or doodle I scrawled was a spadeful of dirt, unearthing a secret tunnel, getting me closer and closer to escape. Laughter was also a lifesaver for me, often literally. Not only is it rightfully considered the best medicine (if used liberally, only as directed), it can also save you from getting your butt kicked in PE.

The point is (yes, there's a point here somewhere), that preadolescence can feel like an eternity when you’re in it, but you actually get through it fairly unscathed, though your body and voice may soon be rendered unrecognizable. This complete freakishness is normal. So let laughter and perseverance be your best and most trusted bodyguards, providing loyal service without even demanding your lunch money in return.

I hope that you enjoy, appreciate, and–above all–buy my book Heck: Where the Bad Kids Go–at least three copies (one for locking away in your safe for future generations, one for reading, and one for travel). I think you’ll find that it’s a story full of laughter and hope (OK, and a fair amount of demons, poop, and dead historical figures). And if you don’t buy it for the story, then buy it for the amazing illustrations by Bob Dob. So, thank you for reading this long-winded essay (assuming you still are) and I caution you to be wary of words such as flummox, maelstrom, and irony. If you find yourself using them, you may already be a–egads–writer.

Cordially,

Dale E. Basye