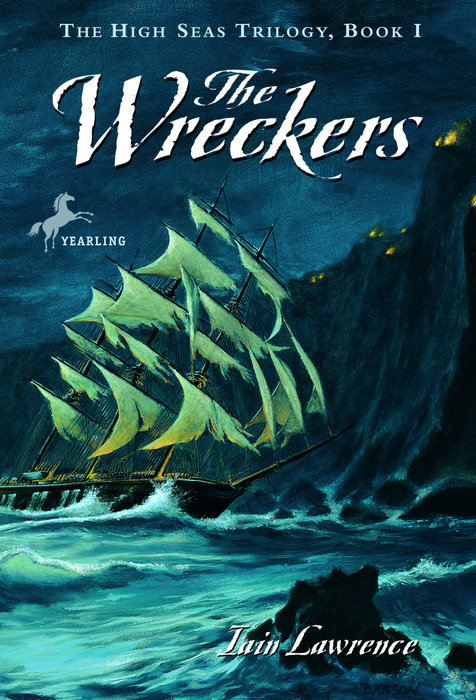

The Wreckers

The Wreckers is a part of the The High Seas Trilogy collection.

There was once a village bred by evil. On the barren coast of Cornwall, England, lived a community who prayed for shipwrecks, a community who lured storm-tossed ships to crash upon the sharp rocks of their shore. They fed and clothed themselves with the loot salvaged from the wreckage; dead sailors' tools and trinkets became decorations for their homes. Most never questioned their murderous way of life.

Then, upon that pirates' shore crashed the ship The Isle of Skye. And the youngest of its crew members, 14-year-old John Spencer, survived the wreck. But would he escape the wreckers? This is his harrowing tale.

An Excerpt fromThe Wreckers

With a great clamor of pounding hooves and groaning wood, the wagon swayed toward us in a boil of dust. The horses were bigger than any I'd ever seen, and they snorted in the harness. The driver cried out to them and shook his reins, and the wagon shimmied across the road. He was a small man, hunched in the seat, wearing a bully-cocked hat white with dust, a neckerchief across his nose and mouth. And over his shoulder rose a woman's face and a flowing mass of pure white hair.

"They say the Widow commands the winds," said Mary. "She raises tempests."

The Widow stood up and held on to the driver's shoulders as the wagon lurched between the ruts. Her face was brown as old parchment, wrinkled like a much-folded map. She looked right at me, with eyes that glowed pink as embers of coal. When the wagon was a dozen yards off, she cried out; not to the driver, but to the horses themselves. The animals bared their teeth and tossed their heads, huffing clouds of fog as though it was smoke they breathed. They slowed to a walk, and their hooves beat a steady march on the roadbed.

The Widow kept her hands on the driver, her feet spaced wide apart. She turned only her head, and stared at me as the wagon rolled past. It was a deep, probing look, and her eyes burned with an awful hatred. I stared back, because I couldn't take my eyes away. I could feel her reaching into my mind, as though fingers crawled in my skull. And still her head swung round as the horses marched on, until it seemed she was looking right back between her shoulders. Then she reached a hand toward me and curled her two middle fingers toward her palm. "Get back!" she said. "Get back where you were!" And she stood like that, staring and pointing, until the wagon rose on the next crest, and dropped out of sight. It looked as though she was sinking into the ground.

"She's put the evil eye on you," said Mary. "You'll have to watch for her."

Our poor ponies had gone half mad. They stood trembling, their ears pressed catlike against their skulls, their eyes rolled up to the whites like hard-boiled eggs. "Hush," said Mary to hers. "Hush now." It flinched when she touched it, then calmed slowly under her hand.

"The Widow's tetched," she said, tapping her head "People say she's a witch, but I think she's just crazy. Years ago she saw her brother drownded. Before that, her husband; his body was never found."

"But the way she looked at me. It was--"

"She thinks you're him come back from the dead." Mary grabbed the pony's mane and sprang up on its back. "It's not just you," she said, looking down. "She thinks the same of any man or boy who gets ashore from a wreck."

"How does she know I came from a wreck?"

"News travels fast." Mary watched as I hauled myself onto the pony. "They probably know of you in Polruan by now, and that's better than twenty mile from here."

We started off down the road, side by side in the Widow's wake. The dust from her wagon flurried ahead of us like a little tornado.

"So there have been others," I said.

"Others what?" asked Mary.

"Saved from a wreck."

"A few," she said, "have reached the shore."

It was all she would say. And then she shouted at me to race her, and set her pony into a gallop for home.

Though we ran at a breakneck speed, we never caught up with the Widow. The cloud of dust moved along at the same pace as ourselves until we turned inland on the path to Galilee. We hurtled round that bend. Mary was a length ahead--the hind hooves of her pony kicked divots of sod as we swung out onto the edge of the moor. She glanced back, and I saw her face through a veil of hair. I leaned forward like a jockey, stretched so flat along the mane that I peered between the pony's ears. I could feel it writhing under me, pounding along like a boat in a seaway. I edged ahead, fell back a bit, surged forward again. Neck and neck we flew over the rise where Simon Mawgan had stopped to look at the view. Mary was laughing. "The loser," she cried, "has to stable the ponies."

Into the glen the ponies ran shoulder to shoulder, paced so closely that their hooves sounded like a single animal. I was on the side closest to the manor; Mary would have to pass ahead or behind.

The path turned to the left. Mary, on the inside, inched ahead. She too was lying flat, her hands right up at the bits. The dust rose around us.

The path straightened, then curved the other way. I could see the opening in the hedgerows. Mary was beside me, her lips dusted gray. And then she was gone.

I could spare only a glance. She'd reined in the pony and passed so close behind that I'd felt a jolt as its head brushed the flanks of mine. And now she was running across the open moor.

As I slowed for the opening, Mary braced her knees on her pony's ribs. She hugged its neck. She aimed it straight for the hedgerow.

I passed through the gateway. And ahead, to the right, Mary's pony came soaring over the hedge. It flew as though winged, carrying her up in an arch, its forelegs clear by a foot, its belly just touching the leaves. And atop it sat Mary, graceful as an angel. She seemed to hang there for a moment, absolutely still. Then she came rushing down, and the pony's hind legs crashed through the hedgerow in a litter of twigs and old leaves. The pony stumbled forward, almost touching its knees to the ground, then straightened and stopped. Mary had beaten me by a dozen yards.

She laughed when I pulled up beside her. "You know where the stable is," she said. "And if you see Uncle Simon, tell him there's a special treat for supper. I made it this morning."

The ponies seemed hardly troubled by their run. They trotted ahead to the stable door, anxious as dogs to be back at their home. And as I came up behind them, I heard Simon Mawgan's voice from inside the building, so loud with anger that he could have been standing beside me.

"Damn your eyes!" he said. "I told you to watch that boy, didn't I? Well, where did they go, then?"

I heard no answer. He might as well have been speaking to himself.

"Just show me!" he shouted.

One of the ponies thumped against the door. Something clattered inside, and Mawgan roared, "Who's there?"

I opened the door. The stable smelled of hay. A dust of corn and oats floated in the light, and through this golden haze I saw Mawgan deep in the shadows with a crop in his raised hand. The other man was lying in a stall; I could see only his boots, and they pushed at the floor as he scrambled back.

The ponies crowded at me, pushing me in.

Mawgan lowered the riding crop and tapped it on his knee. "Where have you been?" he said.

"We went riding," I told him.

"Where?" he barked.

"Across the moor," said I.

"I'll ask once more." He took a step toward me. The ponies clomped through the stable and went each to its stall. "Where have you been?"

"The Tombstones," I said.

"The Tombstones." The crop tap-tapped against his leg. "I didn't say you could go gallivanting across the countryside."

I said, "I didn't know I was a prisoner."

Maybe my boldness surprised him. More likely, he saw through it to the fear inside. He laughed heartily. "A prisoner, you say? No, no, my lad. I was worried about you, is all. I suppose it was Mary's idea, was it? 'Course it was. Headstrong girl, that one."

Then, without turning, he spoke to the man in the stall. "Get up from there. Give the boy a hand with the ponies."

It was Eli, the shriveled old man with no tongue. He came out cautiously, like a weasel from its den. But from the way he held his arms, I could see that the riding crop had done him no harm.

"You've run those ponies hard," said Mawgan. "Put blankets on them, John, then come to the house." He left without another word.

Eli fetched blankets and a comb, all the time watching the door. I held my hand out for a blanket, looking not at him but at the ponies. Mawgan was right; they were starting to tremble with cold sweats. And suddenly Eli clutched my arm.

There were bits of straw stuck in his hair, another piece lying aslant across his shoulder. His face was shrunken and cracked like old mud. And the sounds he made, from deep in his throat, were the croakings of a frog.

I pulled away from him; I couldn't bear his touch. But he came at me again, bent and shuffling, and grabbed my sleeve with a hand that was more like a claw, the skin stretched over talon fingers. He made the sounds again, the awful groans and warbles, and cast another frightened glance at the door.

I dropped to my knees and hauled him down beside me. I swept a bit of dirt clear of old straw and scratched words with my finger: "Show me."

He yanked on my arm, and yanked again, until I looked up at his face. He shook his head so violently that bits of straw flew like arrows from his hair.

"You can't read?" I said. "You can't write?"

Again he shook his head. And then, as slowly and as carefully as he could, he spoke three words. But they were mere sounds, with no more sense than the grunting of a pig.

I said, "I don't know what you're telling me."

He nearly howled with frustration. Then he swept the dirt clear of my writing, and with a finger long and bony he drew a stick figure.

It was bent forward, running furiously. Eli added a round head, a gaping mouth and startled, widened eyes. He jabbed his finger at the running man, then poked me in the ribs. And he spoke again, those horrible groans. Three words.

"Run for it?" I asked. "Run for it?"