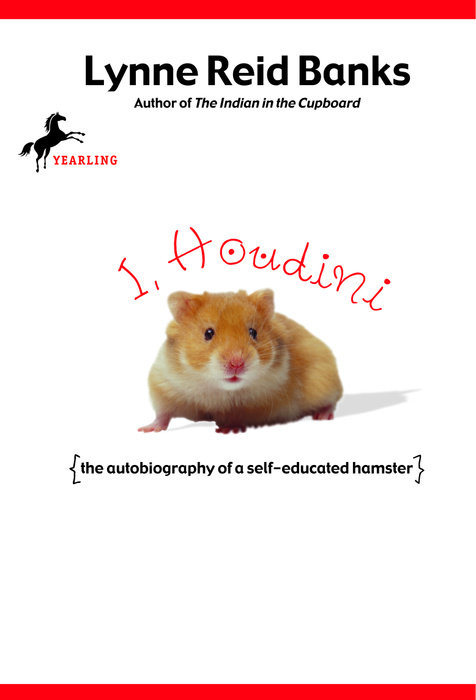

I, Houdini

One family’s household has been in a state of disarray because of one small furry problem. Meet Houdini, an extraordinarily brilliant escapologist. No, not that Houdini. This one is a hamster. Once you meet him, you will understand that his owners just couldn’t name him anything else, for his name is quite fitting. He can escape from anything—a cage or the clutches of a mean cat. While on his escapades, he causes all kinds of trouble from chewing through wires to causing a flood. But Houdini thinks it’s all worth it, because he is desperate to explore the great Outdoors. But once he gets out, will he ever come back? Or will this be his final escape?

An Excerpt fromI, Houdini

Chapter 1

I am Houdini.

No, no, no. Not that one—of course not. He’s dead long ago. Besides, he was a human being and I am a hamster. But let me assure you that, as my namesake was no ordinary man, I am no ordinary animal.

Well, that much is fairly obvious, isn’t it? I mean, what ordinary hamster even knows he’s a hamster? What ordinary hamster can think, reason, observe—in a word, educate himself? Show me the hamster, anywhere, with an intellect, a vocabulary like mine! You can’t. Nor can you show me one that can live with humans on a footing of absolute equality because he can understand their language, and because, quite frankly, he has more brains in his head than most of them have.

I fear you will think me conceited. I assure you I’m not. It’s merely that I have a just and objective appreciation of my own exceptional qualities. It would be as futile to deny that I am exceptional as it would be for an ordinary hamster to boast that he was my equal.

Besides, if I were conceited, I would claim to be perfect. I don’t. Certainly not! I have my faults and weaknesses, my moments of frailty. I, too, have made mistakes, succumbed to temptations. But I think I may fairly claim to have built up my character, over the months of my long life, until not many fingers could be pointed at me in accusation. Indisputably I conduct myself with more wisdom, ingenuity, and restraint than many of the humans I see about me—not that that’s saying much.

Here, then, is the story of my life so far. From it you may judge if I am not, in truth, as extraordinary in my ways as the Great Houdini was in his.

My birth and infancy are almost lost in the mists of memory. I think I may have begun life in a pet shop. It was certainly a large, cold, airy place, exceedingly smelly. Every now and then I catch a whiff that carries me back to those dimly remembered early days—when a friend of my family brings a dog to the house, for instance, and once when I met a mouse, which I shall tell about in its turn.

At all events it was not a bad place, and I remember I had companions of my own kind there, who gave me warmth by day when we all cuddled up together to sleep.

It’s strange that, when I think now about living with other hamsters, I shudder with horror at the idea. With one exception I have never seen another hamster since I became mature. And believe me, I never want to. If I ever did see one, I believe I would be overcome with rage, and fly to attack it. Why this should be, I don’t know, for I have a very calm temper as a rule, and despise those who lose their self-control (something I see all too often in this house, I regret to say). So, whatever I have to complain of in my life, it is not loneliness. I am never lonely.

My worst trial here was imprisonment. I say “was” because luckily it happens less and less now. The Father is my worst enemy in this respect. He has very fixed ideas about “pets” (as I suppose I must laughingly call myself, taking the human point of view). “Pets are all right in their place,” he keeps on saying. (He does tend to repeat things, a sign of a small mind.) His notion of my place is, of course, my cage, and wherever and whenever he catches me, he grabs me up and stuffs me back through that dreaded little entrance tunnel and claps in the round stopper. He never seems to believe it when the boys tell him I’ve even found a way round that.

Anyway, it doesn’t worry me too much anymore. The Mother, or one of the children, will soon take pity on me if I just go about it the right way, if I can’t get out by myself. So I just whip up the tubes into my loft, unearth something tasty from my store, and then curl up and go to sleep. I must say it’s quite cozy up there since they put the bits of flannel shirt in, though I much prefer my nest under the kitchen floor. One does tend to prefer a home of one’s own choice, arranged and decorated to suit oneself.

Here I go, rambling on about the present when I really meant to tell the story of my life. I just wanted to make it crystal clear that I am—well, shall we say, rather unusual? Rambling has always been one of my weaknesses. I just have to follow my nose wherever it takes me—and some fine scrapes it’s led me into, I must say!

Well, so I am, as I say, a rather extraordinary and quite exceptional “little furry animal,” as some people call anything smaller than a pony that runs around on four legs and can’t actually talk. I call them large hairless animals, and I try to use, in my thought, the same degree of superiority that humans do about us. I must admit that nothing infuriates me more than being treated as a pet, picked up, stroked (usually the wrong way), made to climb or jump or run or whatever it is my supposed owners want—and as for eating from their hands and all that sort of degrading nonsense, I’ve not time for it.

Mind you, my protest against this sort of thing is, nowadays, limited to trying to avoid it by escaping, which is my specialty (hence my name). I wouldn’t dream of biting, which I regard as very uncivilized behavior. “Brain, not brawn” is my motto. Besides, they’re so vulnerable with their bare skins, it’s not really sporting when you’ve got jaws and teeth like mine. I won’t say I’ve never bitten anyone, but the feeling of shame I had after letting myself go was awful, not to mention the disgusting taste. . . .