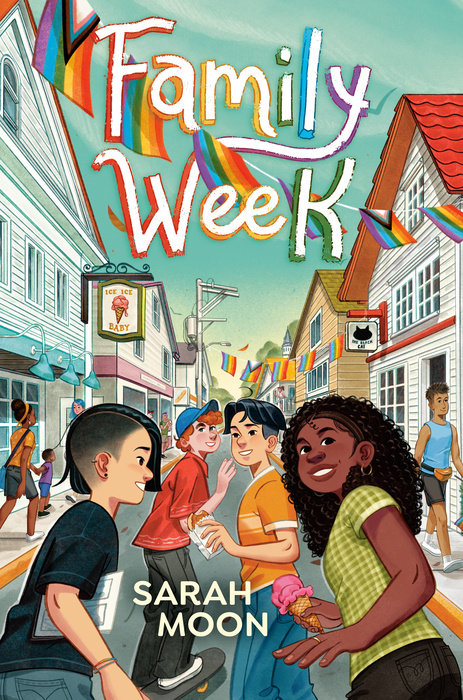

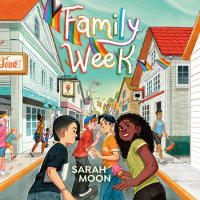

Family Week

Author Sarah Moon

Family Week

Four best friends spend Family Week together at an annual gathering of LGBTQ+ families in Provincetown, MA—the largest of its kind across the world—in this middle grade coming-of-age story that celebrates identity, acceptance, and found family.

For as long as they can remember, Mac, Lina, Milo and Avery have celebrated Family Week together in "the smallest, gayest town in the world"—Provincetown, Massachusetts.

But this summer, their big rented beach house feels different. Avery’s dads are splitting up, and her life…

Four best friends spend Family Week together at an annual gathering of LGBTQ+ families in Provincetown, MA—the largest of its kind across the world—in this middle grade coming-of-age story that celebrates identity, acceptance, and found family.

For as long as they can remember, Mac, Lina, Milo and Avery have celebrated Family Week together in "the smallest, gayest town in the world"—Provincetown, Massachusetts.

But this summer, their big rented beach house feels different. Avery’s dads are splitting up, and her life feels like it’s falling apart. Milo’s flunked seventh grade, which means everyone is moving on to bigger and better things except for him. Mac’s on his way to a progressive boarding school that lets transgender kids like him play soccer, but it means leaving his twin sister, Lina, and his moms—and the safety of home—behind.

Everything is changing, and for Lina, it feels like it's happening with or without her. Avery, Milo, and Mac know this is going to be their last summer together. But Lina can't accept that—and if she can make this the best summer ever, maybe she'll convince them that there will be a Family Week next year. Good things might not last in the real world, but they do in P-town.... Right?

An Excerpt fromFamily Week

Saturday

Milo and Lina woke up at the same moment, the same way they had the third Saturday in July ever since they could remember: their moms blaring “We Are Family” through every speaker in the house and laughing hysterically at their own joke.

Milo heard Mom singing at the top of her lungs in Lina’s room and knew that it would be only seconds until Ma opened his door, practically screaming “Good morning! Let’s gooooooo!” as she threw rainbow bead necklaces into his room. They would scatter onto the dictionaries he’d left open on his desk the night before.

Last month, Mom had insisted on going to clean out Gong Gong’s house by herself, after his last stay at the last hospital, his sixth in the last year. “I might be the one with the tattoos,” Ma said, “but Mom is the tough one. She needs to go clean out your Gong Gong’s house by herself. When she gets back, that’s when she’ll fall apart.” Ma was right, of course. The night Mom got back, they ordered…

Saturday

Milo and Lina woke up at the same moment, the same way they had the third Saturday in July ever since they could remember: their moms blaring “We Are Family” through every speaker in the house and laughing hysterically at their own joke.

Milo heard Mom singing at the top of her lungs in Lina’s room and knew that it would be only seconds until Ma opened his door, practically screaming “Good morning! Let’s gooooooo!” as she threw rainbow bead necklaces into his room. They would scatter onto the dictionaries he’d left open on his desk the night before.

Last month, Mom had insisted on going to clean out Gong Gong’s house by herself, after his last stay at the last hospital, his sixth in the last year. “I might be the one with the tattoos,” Ma said, “but Mom is the tough one. She needs to go clean out your Gong Gong’s house by herself. When she gets back, that’s when she’ll fall apart.” Ma was right, of course. The night Mom got back, they ordered food from Mr. Wonton, the place they always ordered from when Gong Gong came to visit, and Mom cried into her broccoli and bean curd. That night, she gave Gong Gong’s dictionaries to Milo. One Hunanese-Vietnamese dictionary from 1945, when Gong Gong’s family moved to Vietnam, and a 1975 Vietnamese-English dictionary from when Gong Gong and Bà moved to New Hampshire.

Milo was supposed to be working on the translation of The Phantom Tollbooth, the book he and Lina had loved as little kids. They were going to make a graphic novel version, Lina doing the pictures and Milo translating each chapter into a different language, but lately he’d just been staying up late with Gong Gong’s old dictionaries and avoiding the illustrations Lina dutifully left him. Last night’s installment, chapter seven, was buried under the dictionaries. He hadn’t even made it past chapter two, and he was leaving for Truegrove in just a few weeks. He pushed it from his mind as he headed into the hall to wait for the bathroom.

“Lina! Hurry up!” Despite the fact that his twin sister always got up later than him, she always managed to sneak into the bathroom seconds before him. It would have been infuriating if it hadn’t been somehow kind of impressive. “Grmpphhhh” came Lina’s still-asleep answer through the door.

“Lina, I swear to god, you know we have like half a second until Ma’s mood goes from ‘We Are Family’ to ‘The Traffic on the Bridge of Doom,’ and if I have to endure two hours waiting to get on the Bourne Bridge while Ma fumes and demands silence so that she can ‘concentrate’ on sitting in traffic, you are dead to me.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, Milo. I am a delight behind the wheel,” called Ma from her bedroom, coming to the door and raising a single eyebrow at him.

“Totally, ha ha,” said Milo as he banged on the door again. “Lina!” he pleaded. The door opened and Lina pushed past him, looking somewhere between zombie and sloth. This was beyond sleepy, even for Lina.

“Whoa. You okay?”

“Yeah. Tired. All yours.” She went into her room and closed the door. She wasn’t okay, of course. And “tired” didn’t cover it. She hadn’t slept all night. She sat down on her bed like she was trying to cause it harm--punish it for not doing its job last night. But she knew that it wasn’t the fault of twisted sheets or hot pillows. She hadn’t slept that night for the same reason she hadn’t slept so many nights since New Year’s Eve: because she couldn’t stop thinking about Avery. But now the day had finally come. For the first time in a year, she would see Avery, and she had no idea what to do. For the moment, the answer was the same as always: do nothing. She sat and stared at the yellow dots on her blue rug until they blurred, then she closed her eyes. Her door flung open. The knob always hit the same spot on her wall, and the gray paint had started to chip.

Mom walked over the tornado of clothes on the floor and sat next to Lina. “Lina, my love, my cherub, heart of my heart, if you don’t get your butt out of this bed, I will have to join forces with your brother and kill you right there on the Bourne Bridge while Ma takes her cleansing breaths because there’s an iota of traffic--” As if on cue, Ma called up from downstairs.

“Julia! Where are you? Where’s Lina?”

“We’re coming, Em, promise,” Mom said sweetly. She grinned at Lina and nudged her in the ribs. Mom could make Lina smile even when she didn’t want to. She couldn’t quite muster the strength for an actual smile on this little sleep, but she felt her face warm up a little, and she stood up. “Ma knows that there’s never not traffic on the bridge, right? If we leave now or in forty-seven minutes, still, there will be traffic.”

“She knows. Pack quick--we both know you haven’t started yet,” Mom said, tossing Lina’s duffel onto her bed. Lately, Lina hated all her clothes. Nothing felt quite right. Everything was either too tight or too big or too kiddie. She put on her jean shorts and an oversize black T-shirt and flipped her hair to the side to show off her undercut and the cartilage piercing that her moms had let her get for surviving seventh grade (though she knew it was really a pity present for Milo’s imminent departure). She hoped she looked cool and kind of vintage, but her stomach twisted with the fear that she probably just looked like she was trying to look cool and kind of vintage. She started shoving her least horrendous clothes into her bag (mostly from off the floor) and threw a pair of flip-flops on top, along with the new bikini she had begged her parents for (though now, thinking about wearing it in front of Avery made her want to vomit). She added a pair of black shorts and another enormous black T-shirt. Maybe that would be her bathing suit this year.

“Lina!” Ma called from downstairs. Lina could see her standing by the front door, tapping the floor with her foot, tapping her watch with her car key.

“Coming!”

Milo was probably already down there with his perfectly packed matching luggage. (What thirteen-year-old asks for luggage for his birthday? Milo, of course. Or maybe any thirteen-year-old about to abandon their entire family for boarding school--matching luggage was probably a requirement for the snobs at Truegrove Academy.) She tried not to look at his room as she dragged herself down the hallway, tried not to imagine how empty it would look in just a few weeks.

The call had come out of nowhere on the last day of school. Milo and Lina had burst through the door with the kind of joy that only a Tuesday in late June can bring, summer stretching out its arms, every drama, injustice, and boring class behind them. It was Lina’s last day of seventh grade, Milo’s last day of eighth. Yes, they were twins, but Milo had skipped first grade once his kindergarten teacher realized that he was reading full chapter books during naptime and writing them during finger painting. It was weird at first, but they were both used to it now. Lina figured that if they were in the same class, people would still think of her as the less smart twin; this way, most of the time, people just didn’t believe they were twins, which stung in a different way. But that was other people. When Lina and Milo were together, there was no doubt about their shared--well, everything. They communicated silently; even their moms would refuse to play board games with them because they could cheat without saying a word. They had endless inside jokes that only required a word, phrase, or head nod to crack the other one up. September would mark the first time that they wouldn’t be in the same school anymore, but Milo had assured Lina that he’d just be warming Beechwood High School up for her.

They walked in, sweaty and jubilant, throwing their backpacks down with extra force. Ma and Mom were sitting on the couch so they could catch Milo as soon as he arrived. “We need to talk, honey,” they said to him. “Alone.” They took Milo through the swinging door into the kitchen. Lina tried hard to listen, but they went out to the backyard. Lina wondered, with that kind of little-kid glee that still showed up sometimes, if he was in trouble. It seemed unlikely, but a twin could dream.

Milo was not in trouble. Ma and Mom sat across from him at the picnic table. The same one that Milo and Lina had dripped countless ice pops on between runs through the summer sprinkler. The one where they would cut their birthday cakes in just a few days.

“Milo, this afternoon we got a phone call from Edward Sanchez. Do you know who that is?” Mom started.

Milo shook his head, nervous, and tried to glower at Lina, who was listening from the kitchen window now.

“He’s the head of Truegrove Academy,” Ma explained.

“Whoa,” said Milo. Everyone knew Truegrove, the school on the other side of the state for rich kids and brainiacs (and most definitely rich brainiacs). There were many rumors about Truegrove at Beechwood Middle--everything from the obviously false “sidewalks paved with gold flecks” to the more believable, and enviable: state-of-the-art labs, nationally ranked soccer team, and classes in everything from astrology to zoology. “Why?”

“Well,” said Mom, holding Ma’s hand, “Mr. Adams called him about you. He told him about your language skills, your grades, your goalie stats from this year, and--”

“They’re offering you a spot for the fall,” Ma interrupted.

“Me?”

“Yes, you,” Mom said, smiling. “It’s not so hard to believe, Milo.” Milo looked down. He hated compliments. Compliments about his academics were the worst. Everyone praised him for working hard, but the truth was, it wasn’t that hard. He just liked learning, and learning liked him back. His brain built bridges between the imperfect subjunctive in seven different languages all by itself. He couldn’t forget the difference between más and mas if he wanted to. He hated being treated like the prized trick seal at the zoo because of it. But he also hated being bored at school. When his parents told him many years ago, in a conversation not so different from this one, that he would be going straight into second grade, he held tight to their promise: “So you won’t be bored.” But he was bored, and had been for years. He knew he couldn’t just keep skipping grades, and so he kept busy, reading his English book in the original French when he was ahead of the assignment. This year, he was finishing the two-year physics sequence at the local community college. On the first day of class, the professor kept calling him Doogie. When he asked Mom and Ma about it, they explained that it was a reference to a TV show about a boy genius who became a doctor at age fourteen, a show that finished airing twenty years before Milo was born. It didn’t feel great to have it pointed out that the closest thing to a kid like him was a fictional one from 1989.

“You could play soccer,” Mom said gently.

Milo looked up. “Really? They know?” There had been rumbling that the state legislature would take up a bill preventing trans athletes from competing in public school athletics in the next few months. Milo tried not to think about it much; in this purple state, these bills usually didn’t make it out of committee. But it would be nice not to worry about it.

“It’s private--they make their own rules. And their rule is that you get to be you.”

“Isn’t it crazy expensive?”

“Not for the kid who would be blocking goals and winning prizes in seven different languages,” Mom said, so proud.

“They’re offering you a full scholarship,” Ma said. Milo looked at their faces. Joy wasn’t enough. Ebullience mixed with pride and love. Not much room for doubt. Not even for his own.

Ma talked a lot about her grandparents, who had arrived at Ellis Island with not a cent to their name, no English, and a rising tide of antisemitism all around them, not left behind in the old country as they’d hoped. The first thing they’d done after they’d moved off the various couches and floors of the family already in New York was get jobs in a sweatshop and send their kids, Nana and Great-Uncle Max, to school. “Education is everything,” Ma said, all the time.

The only person more intense about school than Ma was Mom, though she tried to be low-key about it. But she, in fact, had the smallest amount of chill. Growing up as the only child of the only immigrants, and only Asians, for miles around in rural New Hampshire had been far from easy, but Mom said it was worth it for the education she’d been able to get. Her parents had sacrificed everything they knew, everything they owned, everyone they loved, to give her the best possible chance at life. Mom tried to use every therapisty muscle in her body to keep Milo and Lina from feeling as indebted to Gong Gong and Bà as she did, but it was impossible not to feel like doing anything short of everything would be disrespecting them.

He took a deep breath in.

“You have to let them know by the end of the week, so think about it,” Mom said.

“Though clearly there’s not a lot to think about,” Ma said, offhand. “I mean, this is the chance of a lifetime. They don’t have Urdu, Portuguese, pottery, and more college acceptances than you can count at Beechwood High. It’s a pretty obvious--”

Mom put her hand on Ma’s leg under the table, her slow down gesture that she used when Ma started to get going.

“It’s your decision, Milo.” But Milo knew that the decision had already been made. Who could say no to this? He tried not to look at Lina’s face, ear pressed against the window screen.

She beat the story out of him the second he walked through the door, literally attacking him with a couch pillow. “Wow, Milo,” she said, her voice higher than he’d ever heard it. “You have to go.” She had sounded excited. And so when she told him he had to go, he decided he would. It was unfortunate, Lina thought, that she could do such a good impression of excitement when what she meant was Dontgodontgodontgo. But that was a problem for a different day. The problem right now was that Ma’s head was about to explode if Lina didn’t hurry it up.