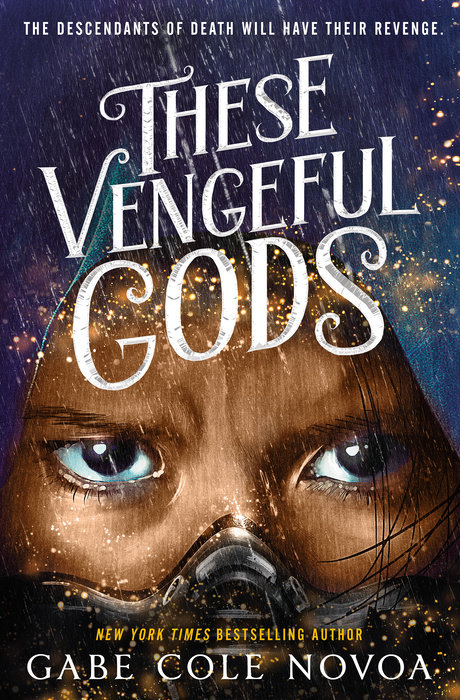

These Vengeful Gods

ALL GODS MUST DIE in this searingly relevant YA from award-winning and New York Times bestselling author of The Wicked Bargain and Most Ardently. In a world bound by violence, a teen descended from the god of Death must keep their true identity a secret as they fight their way through a gladiator-style competition towards victory and rebellion against the gods who murdered their family.

Years ago, the descendants of the god of Death were murdered. The few that remain are in hiding, including Crow, a teen who survived the genocide and hides their magic to stay alive. After fleeing their village, Crow now lives with their uncles in the lowest part of the city: the Shallows.

Life in the Shallows is tough, but Crow’s even tougher. Hiding their magic has made Crow resourceful, cunning, and unbeatable -- which comes in handy as a fighter in the city's lucrative underground fighting ring.

Then, Crow's uncles are arrested for harboring Deathchildren.

With fists tightly clenched, Crow vows to set their uncles free. But to do that, they’re going to need to enter a world that threatens Crow’s very existence. Carefully navigating the politics of the wealthy and powerful, they enter the Tournament of the Gods -- a gladiator-style competition where the winner is granted a favor. As they battle their way towards the winner’s circle, Crow plans to ask the gods for their uncles’ freedom as their reward.

But in a city of gods and magic, you don’t ask for what you want.

You take it.

Action. Adventure. Romance. Find it all in Gabe Cole Novoa's novels:

- The Wicked Bargain

- The Diablo's Curse

An Excerpt fromThese Vengeful Gods

Chapter 1

You call it the worst night of your life, and child, it is also mine.

You’re six years old when you wake to the sound of arguing just outside your bedroom window. Perhaps, on another night, you might have rolled over and gone back to sleep, but tonight your dreams are plagued with smoke and flame and blood.

(It is the first time, but it will not be the last.)

So instead you sit up and roll out of bed. Your bare feet pad on the cool slate floor. You stand on the tips of your toes to peer out the window. The darkness is complete, and the arguing figures are illuminated by the light of your neighbor’s open door.

Who is arguing outside Lark’s house? you think, and even though you don’t get along with Lark, that recognition of her home is enough to spark your interest.

No one notices as you step outside and slip soundlessly into the shadow of the near-full moon. The arid earth is hard and dusty beneath your toes as you move toward the arguing adults. The cool air of the desert night makes you shiver, but you don’t turn back. With a start, you recognize the voices: Your mother and Lark’s mother are arguing in a poor attempt at hushed voices.

“Have you lost your godsdamned mind?” Lark’s mother hisses. “If you think I’ll let you leave Homestead with my daughter—”

“Then come with me,” Cara says urgently. “Bring the family. If we hurry—”

“If it’s such an emergency, why aren’t you leaving with your child and Falcon?” Lark’s mother responds. “Shouldn’t you be prioritizing your family over mine?”

Cara shakes her head. “Those with Deathmagic don’t have a chance—”

“Mom?” The word bursts out of you before you can stop it. Your mere curiosity has twisted into something sharper, something more urgent. It twists in the center of your chest, ratcheting your pulse to discomfiting levels.

Lark’s mother and yours both jump. Lark’s mother covers her mouth with her hand while Cara spins around to face you, wide-eyed. But the shock on her face disappears in a blink, so quickly you question whether you imagined it altogether. Her expression smooths into something placid and placating. She smiles at you, and it’s a balm to the buzzing energy gathering in your stomach.

“Dear,” she says softly, “what are you doing out of bed? It’s late, my sweet.”

The pet names are . . . odd. It’s been well over a year since your mother has called you dear or her sweet. But if she doesn’t seem concerned, then maybe you have nothing to worry about. If she’s smiling at you and being kind, then maybe that’s all you need to breathe in the cool night air.

“I had a bad dream,” you say. “And then I heard you arguing.”

“Oh, sweetie.” Cara laughs lightly and crosses the space between you, placing her hands on your shoulders and turning you gently back toward the house. “We aren’t arguing, we’re just having a discussion. Come, let’s get you back to bed.”

As your mother steers you toward the house, you glance over your shoulder at Lark’s mother, who is standing stricken and pale in the doorway of her own home. When she meets your gaze, she frowns, then retreats inside, closing the door.

In your room, as your mother tucks you into bed (which is odd, isn’t it? She never tucks you in, not anymore), you bite your lip and ask, “Are you leaving Homestead with Lark?”

Cara arches an eyebrow. “Leaving Homestead with Lark? Why would I do that?”

You don’t know. It’s no secret to you, even at six, that your mother likes Lark more than she likes you, that Lark is the daughter your mother expected you to be, but that doesn’t explain why Cara would leave with Lark.

Cara runs her fingers through your hair, pushing your fringe out of your face. “You must have dreamed that. I’m sure you’re very tired, it’s late and you should be asleep. Go to sleep, dear one. I’ll see you in the morning.”

You’re quite sure you didn’t dream it, but this—your mother being sweet and gentle and lulling you to sleep—this must be a dream. It’s a warmth you crave, a kindness you need. So when your eyes drift closed, you don’t fight it. And when your mother presses her soft lips to your forehead, you smile.

It’s a beautiful dream you don’t want to wake from.

But you do. And when you wake, it is to smoke, and flame, and blood.

Chapter 2

The bell rings and the hulking fortress of a man who is my opponent does exactly what you’d expect from someone who calls himself the Great Rhinoceros: He charges. I slip out of the way, letting his arm graze mine as his momentum carries him past me. The contact isn’t strictly necessary for what I do, but it makes it a hell of a lot easier.

Because the moment his skin touches mine, magic sparks invisibly between us, scanning his body from head to toe. A picture of energy flashes in my mind, outlining his every tendon, every nerve, in a perfect representation of his body. In the space of a blink, red bursts through the represented nerves in my mind, like drops of neon dye bleeding into a glass of water. The red highlights a bad left ankle and some bruising around his right rib cage. His fingers are weak from breaking too many times, and his footwork is sloppy.

So this won’t take long.

Rhino man’s sheer mass has carried him to the other side of the ring. He turns around, glowering at me. “This isn’t a dance. Fight me!” he screeches.

I keep my stance wide and beckon him forward. His eyes narrow. The Rhino charges again, roaring as he rages toward me.

One, two, three steps toward me and he’s closed the distance between us in half. I don’t move, not until he’s within arm’s reach. He swings. I duck out of the way, pivot, and slam the side of my foot into his weak left ankle.

He screams. The combination of the momentum of his missed punch and the crumpling of his ankle sends him sprawling onto the floor. I take three large steps back, out of reach, and wait. I need him on his feet, where his bulk—and now his screaming ankle—will make him clumsy. Engaging him while he’s still on the ground, where his weight could crush me, would only give him the advantage.

Rhino man scrambles back to his feet, chest heaving, his face contorted into an ugly grimace, which I can see because, unlike most of us down here, he isn’t wearing a filtration mask. His ankle is pulsing a deeper red in my mind’s eye, so the pain must be pretty bad, even if he tries not to show it. His eyes glint with malice. He growls—literally growls like some animal—before charging forward again.

This time he leads with his right side, presumably to make it harder for me to target his ankle again. His bruised ribs would be more easily accessible, except he has his arm and elbow covering them, ready to ram me, so that’s not going to work—at least, not from the front.

I slip out of the way when he gets close again, but this time he’s ready for my dodge. He pivots on his right foot, spins back, and swings his left elbow out for a jab. I duck beneath his arm and twist to face his rib cage. I make a quick set of punches, my wrapped knuckles connecting with his now-unprotected ribs. I land three jabs, then twist out of the way.