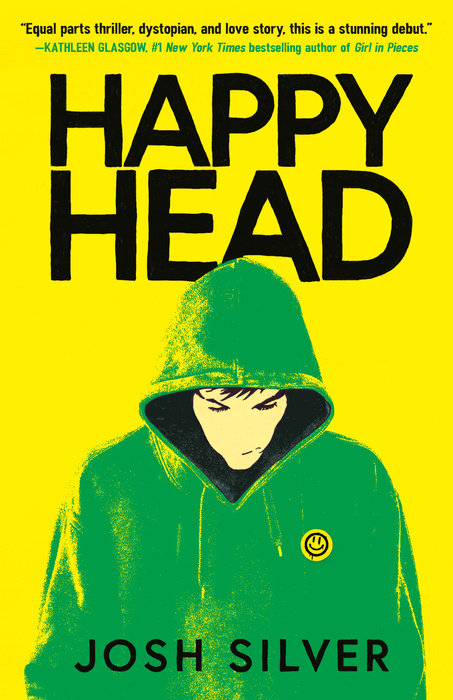

HappyHead

Author Josh Silver

HappyHead

HappyHead is a part of the HappyHead collection.

A bold new dystopian thriller about an experimental mental health retreat center for young adults where everything is not what it seems—and one boy who will risk everything to escape.

Seb has been selected for a new experimental mental health center called HappyHead, designed to solve the national crisis of teenage unhappiness. There he and fellow participants will complete in a series of assessments meant to test them, so they can better face the challenges of…

A bold new dystopian thriller about an experimental mental health retreat center for young adults where everything is not what it seems—and one boy who will risk everything to escape.

Seb has been selected for a new experimental mental health center called HappyHead, designed to solve the national crisis of teenage unhappiness. There he and fellow participants will complete in a series of assessments meant to test them, so they can better face the challenges of the real world. Seb is determined to win so he can change how people see him and make his parents proud.

But then Seb meets a mysterious participant named Finn who has drawn unwanted attention to himself by resisting the program’s rules. The leaders want everyone to believe Finn is mentally unstable but as Finn exposes cracks in the system around them, Seb is left questioning the true nature of the challenges--and wondering if Finn is actually the only one he can really trust.

Something sinister is at play…and as the assessments take a dark turn, it becomes impossible to ignore the voice in his head telling him that even if he wins, there might be no way out.

An Excerpt fromHappyHead

One

Bowie Sky

“I think it’s down there,” Mum says.

“We’ve already been down there,” Dad says, more rudely than I expected.

“No, it’s a different road—look.”

“They all look the same.”

“No, that one’s narrower than the others.”

“What does the GPS say?”

“It’s not working. It thinks we’re in the middle of a field.”

“We kind of are in the middle of a field,” Lily chips in.

It’s unfortunate that I’m spending my seventeenth birthday with my face pressed against the car window for eight hours as my parents and sister talk without coming up for air. But they wanted to see me off. I said they could have done that from the front porch, but they didn’t think that would have been meaningful.

I think it would have been meaningful. The meaning being that I could have gotten the train and avoided this. I could have seen Shelly last night and said goodbye, and not got up at four-thirty to the sound of Dad waving a box of chocolate Cheerios…

One

Bowie Sky

“I think it’s down there,” Mum says.

“We’ve already been down there,” Dad says, more rudely than I expected.

“No, it’s a different road—look.”

“They all look the same.”

“No, that one’s narrower than the others.”

“What does the GPS say?”

“It’s not working. It thinks we’re in the middle of a field.”

“We kind of are in the middle of a field,” Lily chips in.

It’s unfortunate that I’m spending my seventeenth birthday with my face pressed against the car window for eight hours as my parents and sister talk without coming up for air. But they wanted to see me off. I said they could have done that from the front porch, but they didn’t think that would have been meaningful.

I think it would have been meaningful. The meaning being that I could have gotten the train and avoided this. I could have seen Shelly last night and said goodbye, and not got up at four-thirty to the sound of Dad waving a box of chocolate Cheerios in my face, claiming they were a fun treat, before I left.

Going to HappyHead will do me a world of good, Mum is now saying. I should be thankful that I was selected. Grateful.

“It’s a blessing.” She loves that word. “Truly,” she says as she catches my eye in the rearview mirror. “You’ve always had a bit of a sensitive nature, haven’t you?”

I think she might actually want an answer.

Lily snorts.

“I—”

“And we love that about you, Seb. We do. You’ve always felt things very deeply.” Christ. “Not that it’s a bad thing. It’s . . . part of who you are. What makes you special.” I want to open the door and jump into the bushes flying past us. “I just worry sometimes about how you’ll cope. Life isn’t easy.”

For a while now, there has been a general feeling among my parents and my teachers that something has to come along to really shake things up for me if I am to equip myself for the Next Phase of Life.

When the letter came, they were all very excited.

HappyHead would be the answer.

It had to be.

They all agreed.

The car is packed with my things, so me and Lily are parted by a bulging suitcase, which is definitely for the best. But it keeps digging into my chest when Dad brakes too hard, which he does all the time. I didn’t want to bring everything from my wardrobe, but Mum insisted. When I said it wasn’t necessary because of the required packing list, she said I could never be too prepared.

“Where even are we?” Lily groans.

“Nearly there,” Mum says, unconvinced. “Just a little tricky on these Scottish roads. Let’s try and enjoy it.”

Enjoy it.

Shelly said she was going to get a bottle of vodka and some weed, and her uncle was going to let us sit at the back of his pub and bring us free drinks.

4:30 alarm, tho, I texted her yesterday. I’ll have to pass if I want to survive the journey. Sry.

I wanted to go to the party.

I did.

Come on, Shelly replied. It’s your birthday buddy and you’re going away for nearly two weeks. You say you’re independent, but they have a hold on you, Seb. You’re scared of them. Always have been. Goodbye. I really hope you make some friends there so it’s not just me putting up with this shit.

I didn’t reply to that. Shelly loves to use full sentences and first-name me when she thinks I’m bailing. And anyway, I don’t always do what my parents say. And if I do, it’s only to make things easier because I can’t cope with the disappointment and the “That’s not like you, Seb.” Also I’ve had weed before and it wasn’t up to much. I became very dizzy, couldn’t feel my body, and threw up in the shower.

Shelly didn’t get a letter from HappyHead.

No one else at my school did.

Just me.

Maybe she’s jealous.

I can see Mum has opened the parent/guardian pamphlet—now covered in coffee rings and with worn edges—yet again. “Oh, Seb. Selected.”

“I’m pretty sure it’s just random, Mum.”

I don’t think she has parted with the pamphlet since it arrived. She’s read it so many times that she practically knows it by heart and sometimes just quotes bits of it at me, like “nurturing strengths” and “athletics track.”

The car is very hot now.

“They must see something in you, Seb. They must. They have to be using some sort of . . . set of standards for the selection process, right? Richard?”

Dad doesn’t answer.

“They’ve never even met me, Mum.”

“And,” she plows on, “you needed a little boost, didn’t you? What with your grades dropping so—”

“Yeah, it’s great, Mum.”

She turns and looks at me, beaming with hope. “I’ve signed all the consent forms. And you filled out the questionnaire thoroughly, didn’t you?”

I nod.

“Good. Mandatory. Gosh. Like the army used to be . . .”

I try to avoid the tone in her voice that can only be interpreted as please, please, please don’t mess this up, son.

I suddenly feel the familiar twist of dread in my stomach. I pull a Jolly Rancher from the wrapper inside my coat pocket. When I press it to my lips, I realize I can’t stop my hand from shaking.

“Can we put Hunky Dory on?” I say.

Lily rolls her eyes so much they go completely white. She loves to act as if I don’t really like David Bowie, as if I just say I do to try to be interesting. But that’s not true.

“Fake obsessed,” she mutters.

“Just wait, Seb. We need a break from music so we can think.” Mum sharply presses the off button on the dashboard so the Lighthouse Family abruptly stops singing.

I’ve never felt the need to explain my appreciation of Mr. Bowie, especially to my schmucky little sister. She thinks I went seeking something out to make me look a certain way because of how painfully bland I am, but I didn’t.

Bowie found me.

She wouldn’t understand the importance of the first time I saw the lightning bolt shuddering down his face on Shelly’s mum’s CD case when I was thirteen.

Or that I stole it.

Or that, when I listened to it, I danced around my bedroom in Mum’s heeled boots, sometimes crying.

I do not need to tell her that.

And I do not need to tell her that he was the first man I ever liked.

And by “liked” I mean liked.

Hot buzzing in my head, can’t focus, can’t think of anything else, talking to his picture under the sheets, want to tear my chest open and cool the pain of not being together on the cold hearts of everyone who has never felt this way type of liked.

I can smell the cheese-and-onion chips Dad is trying to eat while also holding on to the steering wheel. He lifts the bag and pours them onto his face.

“Oh, darn.”

“Eyes on the road, love.”

“Sorry.”

Lily’s headphones start blaring that shitty music she loves. She often says I don’t get her music and that it’s actually really relevant. It’s Christian pop. She loves the churchy pop groups, and for that my parents give her things and drive her to and from freestyle dance class four nights a week and she always has twenty-pound notes rolled up in her purse. She’s fifteen and richer than most people I know. I will never understand it, but apparently that’s what God will do for you.

“Lily, turn that down. Did we put Seb’s regular pills on the form, Richard? I think we missed them. Did we miss them? That’s the kind of stuff they’ll want to know about. And the course of diazepam last year? Richard?”

“We put it all on the form.” I find myself looking for an ejector seat button.

Lily is shrugging her shoulders up and down in some kind of street dance that she must have picked up from all those hours of practice.

“What about the lavender pillow mist?” my sister says. “Do they want to see that on there?”

Mum looks at Dad, worried. “Do they?”

“Funny, Lily,” I say. “How’s the hip-hop coming along? The classes are worth it, I see.”

“Dick,” she says.

“Sorry? Didn’t hear you.” She rolls her eyes. “Louder, Lily.”

D-I-C-K, she mouths. “Come on, Seb. You of all people should understand what that is.” Her eyes flick from her phone to Mum, and she gives a wicked little smile. She’s always threatening to tell them. Blackmailed by a fifteen-year-old. She loves it. Little sadist. She shrugs, casual, in a way that says Try me.

She wants to see me squirm.

I don’t care. They know. They must.

I turn to press my forehead against the cool window, and it fogs with the hot air from my nose.

I focus on the bright yellow fields.

The sky is electric blue today.

A Bowie sky.

Lily pokes her tongue into her cheek so it bulges. “HappyHead. Sounds like you’ll be right at home there, Seb.” She leans back, smug, like she’s won something.

Not long now. And then some peace.

From this.

Nearly two whole weeks.

I stare out the window and watch as the sky darkens, streaking with purple and pink like a new bruise.

Mum sharply inhales. “Did we put about the childhood bedwetting?”

“Yes, Mum,” I say. “Everything was on the form. Just leave it now. Jesus.”

The car bumps along the road, and my head bangs against the glass.

“Watch your language,” Mum says, sounding hurt.

Lily smiles.

Suddenly Dad slams on the brakes. The inertia pushes me into my seat belt.

“Dad!” Lily snaps. “I really, really would prefer not to die before Lola’s birthday party next week.”

“Sorry, everyone.”

I look up at the thick wall of tall reeds that we have nearly just plowed into. The same reeds that have been on either side of us for over an hour now.