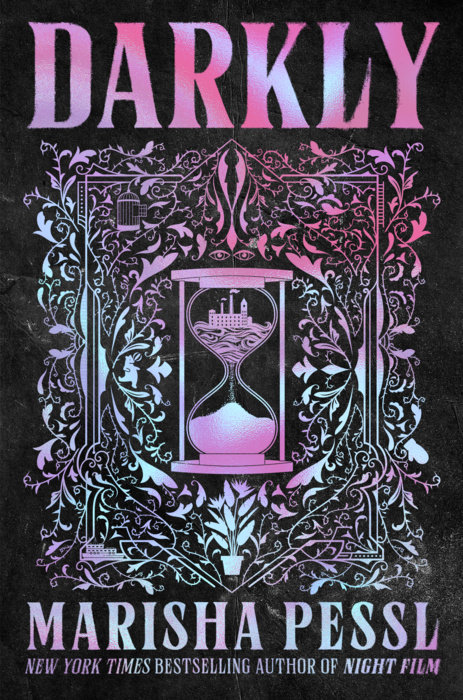

Darkly

#1 NATIONAL BESTSELLER • A must-read thriller that will keep you guessing until the very last page from the New York Times bestselling author of Night Film.

There’s nothing special about Dia Gannon. So why was she chosen for an opportunity everyone would kill for?

“Pessl is gargantuan: wildly smart, extremely surprising, a wordsmith, a queen. Read her.” —E. Lockhart, #1 New York Times bestselling author of We Were Liars

A KIRKUS REVIEWS BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR

Arcadia “Dia” Gannon has been obsessed with Louisiana Veda, the game designer whose obsessive creations and company, Darkly, have gained a cultlike following. Dia is shocked when she’s chosen for a highly-coveted internship, along with six other teenagers from around the world. Why her? Dia has never won anything in her life.

Darkly, once a game-making empire renowned for its ingenious and utterly terrifying toys and games, now lies dormant after Veda’s mysterious death. The remaining games are priced like rare works of art, with some fetching millions of dollars at auction.

As Dia and her fellow interns delve into the heart of Darkly, they discover hidden symbols, buried clues, and a web of intrigue. Who are these other teens, and what secrets do they keep? Why were any of them really chosen? The answers lie within the twisted labyrinth of Darkly—a chilling and addictive read by Marisha Pessl.

This summer will be the most twisted Darkly game of all.

“Complex and captivating.” —Erin A. Craig, #1 New York Times bestselling author of House of Salt and Sorrows

An Excerpt fromDarkly

“What may I bring you for dinner this evening?”

I turn from the airplane window to see the first-class attendant smiling down at me. I study the elegant menu clutched in my hand.

Normandy lamb chops with mint yogurt sauce

Side of roast boeuf with Campagna potatoes and hens of the woods

Poulet anglaise with celeriac compote

“I’ll take the chicken, please.”

“And to drink?”

“Water. Thank you.”

She jots this down and moves to the passenger behind me. I return my attention to the billowing pink clouds out the window, twisting my shoulders into an uncomfortable angle to make sure my face is hidden from the other passengers in row 1.

I am a ball of nerves. I feel more fragile and awkward with every mile I am whisked from home.

I never should have left my mom. I never should have left Prologue or the Barnabys, Basil and Agatha, or Missouri.

Because, with the exception of Missouri, they won’t be able to survive without me. It was clear when I said goodbye this morning. Agatha was whispering to herself, unable to find her glasses, even though they were hanging around her neck on the beaded chain. My mom was tying a price tag of $19.99 on a French garniture set worth $5,000. Basil was stuttering when he asked if I might have time to pick up a Venti coconut latte at Starbucks for him before I left, even though I had just handed him that very beverage. The Barnabys were jumping around like mad, scratching the furniture and leaping onto chandeliers. My mom noted this was a sign all five were about to have kittens, which caused her to wonder how the tomcat got in—the disturbing fact that Prologue Antiques is about to be taken over by a fiefdom of jumpy, black shadow-cats utterly lost on her.

Making matters worse, something else on this plane makes it clear I have no business being here, and upon landing, I should book a flight home and join witness protection.

Because there is another one of us on the airplane.

The boy in 1F.

I first noticed him standing in a bookstore in Terminal 8, when I was trying to find the gate for my connecting flight. He was flipping through an aggressively thick paperback and was so gorgeous that I actually backtracked to make sure he was real, and also to see the title.

Anna Karenina.

An hour later, he was boarding my plane.

He saunters in, tall with moody black hair in his eyes, gray sweats, a cigarette-alley slouch. He sets down two massive leather duffels, one in the aisle so no one can pass, one in the seat beside him that belongs to a bald businessman, who for some reason is intimidated and waits in silent irritation. I notice the side of both bags is emblazoned with a gold Victorian royal pv3, which instantly sets off an alarm bell due to the fact that I have committed the names of the other interns so intrinsically into my brain it’s hardwired to pick up on anything, however minute, that could evoke one of them.

It must be Poe Valois III of Paris, France, age seventeen.

But that’s not even the crazy thing—the boy is carrying a black leather briefcase, and it is handcuffed to his left wrist.

Like some kind of gangster.

Whatever priceless thing is inside, it’s been orchestrated with the airline ahead of time. Because as soon as the flight crew see this boy, they’re on high alert, crowding around him and nodding like he’s a sultan. The boy pulls a necklace from his shirt, revealing a collection of tiny strangely shaped black keys. Using one in the form of a circle to unlock the cuff, which falls open in an accordion way I’ve never seen before, he hands the briefcase to the pilot. With a grave nod, as if it contains the boy’s own beating heart, the man whispers, “Thank you for your trust, sir,” before vanishing with it into the cockpit.

And then—as if nothing at all extraordinary just happened—the boy sits with a yawn, pulls out a laptop covered with cool stickers, and starts to compose a classical symphony using some kind of elaborate composition program.

He writes musical notes across nineteen bars, wearing the same absorbed scowl I once saw on a silver-print portrait of Beethoven—not looking up for an hour. The reason I know it’s a symphony is, at one point, he fusses with the buttons on his headphones and they lose the Bluetooth connection, and the most beautiful, brooding orchestral music I have ever heard blasts out of his computer into first class.

A few people look up in surprise, and he kills the sound.

“Sorry for the disturbance, ladies and gentlemen,” he announces with a sheepish grin.

He has a lilting French accent. So it is Poe Valois III of Paris, France.

Never in my life could I have imagined a boy to make Choke Newington look dreary. But here, impossibly, is such a boy. His hands look like they regularly sculpt life-sized human figures out of wet clay. His eyes are dark yet warm. I find myself thinking it must be the light in first class that makes him so perfect, and upon disembarking in five hours to the harsh fluorescents of an airport, he will devolve into a moderately handsome teenager in keeping with the rest of humanity.

Except why is he on this flight out of New York City? If he lives in Paris, wouldn’t he simply take a train through the Channel Tunnel, or a quick flight from Charles de Gaulle, or use his family’s private helicopter? Because he looks like he regularly enjoys a helicopter. Possibly one of those stadium-sized yachts drifting around the Mediterranean, too.

Everyone smiles and goes back to sleeping or watching a movie. Not me. I can’t take my eyes off him, wondering how I’ll survive a summer working in close proximity to him.

He eats dinner, picking at the Normandy lamb chops.

After that, he uses the bathroom.

After that, he motions to the flight attendant with a shockingly tiny gesture that could only have been learned after spending his childhood in an echoing château—nothing else could explain the expectation that, mais oui, everyone is attuned to his movements at all times. Instantly, the copilot emerges with the mysterious briefcase.

Poe turns on the overhead light, opens the case in his lap, using another one of those odd keys around his neck, and he removes a Darkly game.

I am astonished. It’s an original. Removing an original Darkly in flight, even if it is first class, is like unrolling Andy Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn in a back booth at McDonald’s.

The businessman seated next to him does a double take.

“Is that an—”

“Absolutely,” says Poe with a mischievous smile. “Want to play?”

The businessman chuckles. “Which one is it?”

“Eighteen Lost Icelandic Sailors. 1978. Recover the drowned bodies of the missing sailors, take over their ghost ship, discover why they perished, unearth their hidden diaries that contain their hideous secrets about what went down on their voyage, send their bodies home to grieving families for a Christian burial, all the while trying not to drown, go mad, or be devoured by a twenty-seven-foot sea monster.”

The businessman leans in, studying the ornate wooden board. I’ve seen photographs before, but they did not do it justice. It’s a maritime ocean map emblazoned with the legendary Darkly scroll, carved with detailed circles and nonsensical words, drawings, diagrams, and odd crisscrossing longitudes.

“And that’s—”

“Louisiana Veda’s original prototype. One of two copies in the world.”

“I had a client who bought one,” the businessman notes. “The Death of Alice Something—”

“The Demise of Alice Hayes. One of the ghost games.”

“Ghost what?”

“After Louisiana’s death, they discovered fifteen original games she had created. Never released or mass-produced. They go for the highest prices. Conquistador. Fringe Theory. The Donwaldt Island Mystery. The games released during her lifetime are called the vitals.”

The businessman is rapt. “My client spent a fortune buying the thing. Another on tutors, psychologists, mathematicians to help crack it. He was hell-bent on winning. Poor man died in a car accident without making it even two squares down the board. His wife went nuts. Swore it was the game that killed him. She made sure it left the family. Donated it to MoMA with the provision that it could not be displayed until fifty years after his death.” He frowns. “But is it really wise? Taking that out here? Isn’t it worth, like—”

“Four million pounds. Yes. Do you know what they say about Darklys?”

“Not really.”

“They own you. Not the other way around. Like bloodhounds, they’re loyal to the death. Surprisingly impervious to abandonment. They bond with their first owner and will do anything to be played, again and again. But not won. Never do they wish to be won. People claim if you have a Darkly in the house, put it in the back of your closet under a boatload of junk, forget about it. Within days it’ll be out on a table under a light, waiting. No one will remember putting it there.”

“But it’s all nonsense.”

Poe smiles. “Want to find out?”

The man laughs, an uneasy frown—Who is this kid?—and returns his attention to his spreadsheets.

Though as he types, I notice, he cannot stop looking back at the game.