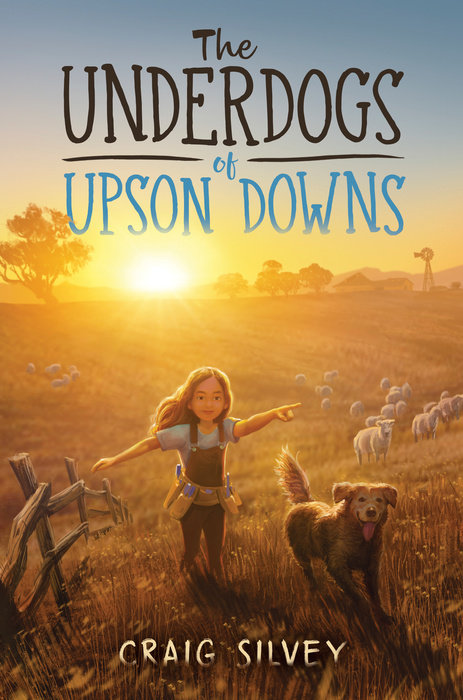

The Underdogs of Upson Downs

A heartwarming and hilarious story about a girl and her dog, and of kindness, friendship, hurdles, tunnels, see-saws, and—most importantly—bringing out the best in yourself and others.

A KIRKUS REVIEWS BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR

Annie Shearer lives in the country town of Upson Downs with her best friend, an adopted stray dog called Runt. The two share a very special bond.

After years evading capture, Runt is remarkably fast and agile, perfect for herding runaway sheep. But when a greedy local landowner puts her family's home at risk, Annie directs Runt's extraordinary talents toward a different pursuit--winning the Agility Course Grand Championship at the lucrative Krumpets Dog Show in London.

However, there is a curious catch: Runt will only obey Annie's commands if nobody else is watching.

With all eyes on them, Annie and Runt must beat the odds--and the fastest dogs in the world--to save her farm.

An Excerpt fromThe Underdogs of Upson Downs

Meet Annie

Annie Shearer lives in the town of Upson Downs.

She is eleven years old and short for her age. She has brown hair and brown eyes.

She lives on a sheep farm with her parents, Bryan and Susie; her brother, Max; and her grandma Dolly.

People in Upson Downs think Annie is a bit different.

They think it’s weird that she wears an old leather tool belt wherever she goes, even though Annie finds it useful having so many pockets to store items that can be used to fix things.

They think it’s odd that they have never seen her laugh, even though she is often quite happy.

They think it’s strange that they’ve never seen her cry, even though she is sometimes quite sad.

They worry she must be lonely, because she spends so much time by herself. But Annie cares deeply about people and quite enjoys her own company--and besides, she has a very best friend.

He is a dog.

And his name is Runt.

Annie knows she is a bit different, but she doesn’t think she is weird or odd or strange. The truth is, everybody is unique. No two people are the same. Even identical twins can have different interests. And it makes the world a more interesting place.

Annie enjoys reading about exotic creatures with hidden talents.

For example, in the darkest depths of the ocean, there’s a fish with a glowing flashlight poking out of its head. It’s called an anglerfish.

In the forests of Australia, there’s a bird that can mimic perfectly any sound that it hears. It’s called a lyrebird.

In Africa, there’s a frog that lives in a bubble of its own snot. It’s called an African bullfrog.

And in Upson Downs, there is Runt.

Runt can’t mimic any sounds, he doesn’t have a light sprouting from his head, and he doesn’t live in a bubble of snot, but his hidden talents are extraordinary.

Right now, Annie is at school.

It’s a very hot Tuesday afternoon, and Ms. Formsby is teaching the class about storms. She points to a chart displaying the water cycle.

“. . . and so the vapor rises way up into the sky, where it collects and condenses into these dark clouds. And when it gets too heavy to hold on any longer, it falls back down. Which is commonly referred to as what?”

Ms. Formsby fans herself with a sheet of paper and looks at her students expectantly.

Only one hand goes up. It is Annie’s.

Ken Bash, in the back corner, is asleep.

“Ken, mind answering this one?”

Ken startles awake, sits up straight, and looks around as though he’s surprised to be there.

“Oh. Uh.” He squints and guesses, “Three hundred and seventy-five?”

The class giggles as Ms. Formsby sighs.

“No, Ken. Math was this morning, mate. The answer is rain. Rain is what falls from the sky. Thank you.”

Ken isn’t finished.

“But three hundred and seventy-five is the number of days since it’s rained in Upson Downs. I heard my dad say it this morning.”

“Is that really true?” asks Ms. Formsby.

“Yes!” the whole class says together.

“It’s awful!” says Claudia Velour, who thinks it’s important to be beautiful. “I’m only allowed to wash my hair once a month!”

“What do you mean, wash your hair?” asks Fiona Grudge, who couldn’t care less about being beautiful.

“My mum reckons if the drought goes on much longer, we might have to sell our farm,” says Dustin Brayshaw.

“Mine said that too!”

“Mine too!”

“We just sold our place,” says Ben Nguyen quietly. “We’re moving to the city to live with my aunty and uncle. I don’t really want to go.”

Everyone feels bad for Ben, including Annie, who is in the back row, tightening a loose screw on the chair in front of her.

Fixing things is Annie’s hidden talent. If something is wrong, she wants to make it right. But some problems are so tricky that it’s not clear how to solve them, or they’re so large that the solution doesn’t fit in her tool belt.

Like the drought, for example.

Or the fact that her family might lose their home too.

A car horn interrupts the class. Everyone goes quiet. The horn honks again.

“Annie! Annie!”

Outside, Bryan Shearer has parked his truck on the grass beside the classroom. He is a big man, with square shoulders and a round beard.

Ms. Formsby pokes her head out of the window.

“Mr. Shearer, there are less disruptive ways to collect your daughter. I recommend the car park and the main entrance, after the final bell.”

“It’s an emergency!”

“Again? This is the third time this month!”

“Can’t be helped, I’m afraid.”

He honks the horn again.

In the classroom, Annie has returned the screwdriver to her tool belt and packed her schoolbag. She moves swiftly toward the door.

“Sorry, Ms. Formsby,” she says. “I’ve already done my homework. It’s on your desk.”

Annie runs down the hall and through the main doors, and rushes to get into the truck.

Because there’s a problem, and only she can fix it.

With Runt’s help, of course.

Upson Downs

Bryan drives through the main street of Upson Downs.

They pass empty storefronts with window banners that say For Sale or For Lease. They pass Patel’s Petals, the florist. Raelene’s Relics, the antique store. They pass the bank, the butcher, and the newsagent. They pass the Golden Fleece, the only pub left in town. They pass the abandoned town hall and the deserted railway station. They pass the Big Ram, a giant statue fallen into disrepair. It has a broken horn and a damaged eye. A sign beneath it says Thank Ewe for Visiting!

But nobody visits anymore.

For more than a hundred years, Upson Downs was busy and thriving. Home to thousands of people and thousands more sheep, Upson Downs was famous for producing the finest wool in the world. The luxurious fleece was praised by Parisian designers and prized by tailors on London’s Savile Row.

The vast plains and valleys were kept green by the deep river and creeks that ran through it. It was a beautiful, vibrant place, full of wildlife and wildflowers. There were restaurants and festivals and dance halls and sporting clubs. There were stockyards and bake sales and charity events. People poured in from across the country, and Upson Downs welcomed them all.

Then everything was ruined by one man.

Bryan’s rickety truck rattles along a single-lane road. Around them are brown paddocks with tufts of dry grass.

“Sorry to come and grab you early again,” Bryan says.

“It’s okay.”

“Hope I didn’t interrupt anything too interesting.”

“We were learning about storms.”

“Oh yeah? Could do with a few of those. You know, your grandpa Wally studied them too at one point. I remember him talking about a harebrained scheme to make his own rain clouds.”

Annie turns to look at him, interested.

“Really?”

“Yeah. It was all about attracting lightning. Something about electrical currents positively charging water droplets to make them heavier. I couldn’t make any sense of it. He was a deep thinker, as you know. Had a lot of wild ideas.”

“Did he write it down?”

“Not sure. I wouldn’t pay it much attention, though, mate,” says Bryan.

It’s too late; Annie is intrigued.

Bryan pulls up outside the Shearers’ old timber farmhouse, bringing a cloud of dust behind him.

And there, sitting in the shade beside his timber doghouse, is Runt.

Runt is three years old and short for his age. He has brown fur and brown eyes. Annie doesn’t know what breed he is. Maybe kelpie. Maybe heeler. Maybe shepherd. Maybe terrier. Maybe all of them. Maybe none of them. Annie doesn’t really care. He’s just Runt, and that’s all that matters.

Bryan winds the window down and whistles.

“Come on, Runt! Get in!”

The dog doesn’t move.

“Come on, mate! In you get!”

Runt doesn’t budge.

Bryan turns to Annie. He smiles and winks.

“Always worth a try,” he says.

Annie’s mother, Susie, and her grandma Dolly both appear outside. Dolly coughs and waves away the last of the dust with a greasy rag. She wears a pair of blue denim overalls and a flannel shirt with the sleeves rolled up. She has short gray hair and brown leather boots.

“The dog won’t listen to you, Bryan, you absolute melon! Go and get Annie!”

“I’m here, Grandma!”

Dolly stoops and squints into the truck.

“Oh! So you are.”

“They haven’t got out again, have they?” Susie asks.

“Afraid so.”

Bryan climbs out of the truck, leaving the door open, and shoos Susie and Dolly away.

“Quick! Back into the house!”

Susie, Dolly, and Bryan all retreat and hide. Carefully, Bryan peeks around the corner of the house.

Once the two of them are alone, Runt looks at Annie, who looks back at Runt. Annie makes the faintest upward nod of her head, and Runt bursts forward, leaps into the truck, and sits happily on Annie’s lap.

Bryan smiles and shakes his head.

Then he hurries to the truck, because time is running out.

The Collector

Across the road from the Shearers’ farm are hundreds of acres of lush green pasture surrounded by white wooden fences. It’s a sprawling oasis, where dozens of thoroughbred horses prance about with glistening coats.

Past the iron gates of the entrance, a long driveway snakes all the way up a steep hill to an enormous sandstone manor. From here, one man surveys the parched plains of Upson Downs.

His name is Earl Robert-Barren.

His home has sixty rooms, yet Earl lives alone and has never entertained a single guest.

A staff of gardeners keeps a lawn tennis court manicured to pristine perfection, yet Earl has never picked up a racquet. The only things he has ever served are papers, because Earl is a senior counsel, which means he is a very formidable lawyer.

His estate has an expansive vineyard, and every year Earl hires the finest winemaker in the country to handpick his grapes and craft his own vintage. Yet Earl has never tasted a glass of it. He keeps every bottle stored away in a dark, cavernous cellar.

Because Earl prefers to collect things.

Not to drink, not to enjoy, not to savor or admire. Simply to possess them.

Earl owns paintings by Pablo Picasso and Johannes Vermeer and Leonardo da Vinci and Vincent van Gogh. None of them hang on his walls. They are sealed in plastic and locked in a climate-controlled storeroom.

Earl has a library filled with the rarest books, from Dickens and Darwin to Austen and Tolstoy. He has never bothered to read a single word.

Earl has a piano that belonged to Beethoven, a bottle of Napoleon’s perfume, and a quill used by Shakespeare. He has sculptures, Fabergé eggs, medieval tools, moon rocks, and hundreds of other historical artifacts.

Earl derives no joy from their beauty, and he feels no awe for their significance. His pleasure comes from owning things that other people can’t have, in hiding things that they desperately wish to see. It makes him feel very powerful and important.

Earl’s most treasured possession is in the center of his property. It is an enormous, deep dam filled with clear, fresh water.

It’s quite easy to make a dam. Even a beaver can do it, and they don’t have hands. If you have a flowing river and a big hole in the ground, all you really need to do is build a wall.

Before Earl Robert-Barren came to Upson Downs, the river gushed from high on a ridge and spread into smaller creeks that supplied the whole town with water. Each farmer took enough for their flock, and on and on the water flowed. They relied on the river, because with every passing year it rained less and less.

Then Earl arrived. Like putting a plug in a bathtub, he blocked the river and collected all the water for himself. And down across the flat plains of Upson Downs, the creek beds dried up, the grass withered and began to die, and so too did the town.

The wool from Upson Downs declined in quality and no longer attracted the interest of Parisian designers or London tailors.

People stopped visiting. The train no longer had reason to come to town, so the station closed. Restaurants and shops struggled to make ends meet, then shut their doors for good. There were no more festivals. No more dances. No more sports.

Farmers were left with no choice but to sell their land and leave. And only one man was prepared to make a paltry offer for their dry paddocks:

Earl Robert-Barren.

Because Earl is as cunning as he is cruel.

As soon as he assumed ownership of a property, Earl installed a long pipe that reached like a tentacle from his dam, pouring water back into the empty tanks and troughs, bringing life back to the parched soil, making it instantly more valuable.

But Earl isn’t interested in selling for a profit. He is collecting the town of Upson Downs, piece by piece, acre by acre. He is collecting homes and hopes and histories and lives, and he will not stop until he has them all.

e faintest upward nod of her head, and Runt bursts forward, leaps into the truck, and sits happily on Annie’s lap.

Bryan smiles and shakes his head.

Then he hurries to the truck, because time is running out.

The Magic Finger

Sheep have an unfortunate reputation for being quite stupid.

People believe they’re dim-witted, aimless animals that are easily confused. But this is a bit unfair.

For example, sheep have very long memories. They never forget a good patch of grass, and they certainly never forget where to find a decent drink of water.

Think of your favorite food, prepared by the world’s most talented chef, laid out on a banquet table that spreads out for miles. This is what Earl’s pasture looks like to Bryan Shearer’s sheep. It’s irresistible. Which is why, despite Bryan’s efforts to repair his rickety old fence, they persist in pushing their way through it, crossing the road, and squeezing onto Earl’s estate.

The grass really is much greener on the other side. Earl’s estate is paradise. They bleat and bounce about, trotting and kicking up their hooves. They stuff themselves with tufts of juicy grass, then wash it all down with a refreshing drink from Earl’s dam.

And today, while Annie was at school learning about cloud formation, a storm was brewing on the outskirts of Upson Downs, because the sheep had broken out again. And Earl, peering through a brass spyglass that once belonged to the pirate Blackbeard, had spotted them.

He snatched up his telephone and poked the buttons urgently, like he was trying to wake a hibernating bear. And he yelled at Bryan Shearer for so long that he didn’t realize Bryan had already hung up and left to fetch Annie.

Bryan’s truck hurtles up the long driveway and stops outside the manor.

Earl stands impatiently on the stone steps. Despite the heat, he wears a double-breasted navy jacket with silver buttons and a purple silk cravat. He holds a gold pocket watch previously used by Winston Churchill.