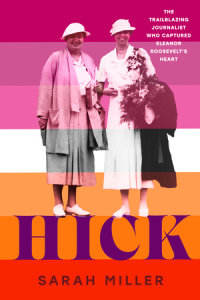

Hick

Author Sarah Miller

Hick

In this riveting YA non-fiction set against the backdrop of the Great Depression, trace Lorena Hickok--or Hick's-- rise from devastating childhood to renowned journalist, and watch as she forms the most significant friendship and romantic relationship of her life with first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt.

Lorena Hickok came from nothing. She was on her own from the age of 14, cooking and scrubbing for one family after another as she struggled to finish school. But the girl…

In this riveting YA non-fiction set against the backdrop of the Great Depression, trace Lorena Hickok--or Hick's-- rise from devastating childhood to renowned journalist, and watch as she forms the most significant friendship and romantic relationship of her life with first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt.

Lorena Hickok came from nothing. She was on her own from the age of 14, cooking and scrubbing for one family after another as she struggled to finish school. But the girl who secretly longed for affection discovered she had a talent with words.

That talent allowed Hick to carve out a place for herself in the male-dominated newsrooms of the Midwest where she earned bylines on everything from football to opera to politics. By age 35 she’d become one of the Associated Press’s top reporters.

At the moment her career was taking off, Hick was assigned to cover Eleanor Roosevelt during FDR’s presidential campaign. By the close of 1932, Hick was head over heels in love with the wife of the president-elect. And her life would never be the same.

Acclaimed author Sarah Miller read the 3500 letters that exist between Lorena Hickock and Eleanor Roosevelt to reconstruct their friendship and love, and bring Hick's story to a new generation.

An Excerpt fromHick

Chapter 1

No headlines proclaimed her birth on March 7, 1893. Alice Lorena Hickok was one of a thousand or so babies born in the United States that day and attracted no particular notice outside her own family. There was not one single reason to suspect that this baby girl—born over a creamery in East Troy, Wisconsin, to a butter maker and his wife—would one day reside at the White House.

--

From the very first, Lorena proved herself a keen and quiet observer. Even as an infant, she watched and listened, slowly, carefully absorbing the sights and sounds that orbited her. As she thought of it years later, she was acclimating herself to the world, learning how things felt, moved, smelled, tasted, the way babies of every species must. But Lorena seemed to do it more deliberately—so deliberately, in fact, that she managed to hold on to some of her earliest babyhood experiences tightly enough to keep them from fading away entirely.

Light was her first memory, “warm and yellow.” Light, and then music. It had no form or…

Chapter 1

No headlines proclaimed her birth on March 7, 1893. Alice Lorena Hickok was one of a thousand or so babies born in the United States that day and attracted no particular notice outside her own family. There was not one single reason to suspect that this baby girl—born over a creamery in East Troy, Wisconsin, to a butter maker and his wife—would one day reside at the White House.

--

From the very first, Lorena proved herself a keen and quiet observer. Even as an infant, she watched and listened, slowly, carefully absorbing the sights and sounds that orbited her. As she thought of it years later, she was acclimating herself to the world, learning how things felt, moved, smelled, tasted, the way babies of every species must. But Lorena seemed to do it more deliberately—so deliberately, in fact, that she managed to hold on to some of her earliest babyhood experiences tightly enough to keep them from fading away entirely.

Light was her first memory, “warm and yellow.” Light, and then music. It had no form or melody. Just a vague and gentle humming, accompanied by the soft sway of the rocking chair where Anna Hickok often tucked her baby daughter into a nest of pillows while attending to the household chores.

Perhaps Lorena’s mother hummed as she worked. Or perhaps the music came from the baby herself. “Ever since I can remember, through almost every waking hour,” she would muse as a grown woman, “music has run through me, somewhere in the back of my throat.” The sounds were like a current, as constant as the movement of blood through her veins.

She took her time learning to talk—so long that her mother’s family began to whisper their worries among themselves. Here was a child who would rather have inaudible conversations with cows than talk with people, a child who secretly believed the animals could converse among themselves just as humans did. She seemed more intent on deciphering the language the hens spoke than on bothering with English, and snuck about the chicken yard, trying to surprise the birds into divulging their gossip.

Human companionship offered little to Lorena, compared to the raptures of the natural world. “In the memory pictures of my very early life there seem to be no people at all,” she recalled. “No real people—only here and there a shadowy figure.” The earth, the grass, the tiny insects crawling through it—these she would remember vividly. She regarded trees with the same fondness that most children reserved for a beloved parent, “wide-spreading trees that sang to a child and might sometimes reach down and pick her up in their strong, rough arms.”

It required a near cataclysm to make Lorena take notice of the living, breathing people around her. One day she stood in the kitchen doorway during a thunderstorm as her grandfather navigated the single-board walkway that led to the barn. The wooden walkway was slick with rainwater and shone faintly blue each time the sky flared. Suddenly, her grandfather slipped. At the same instant, “a sizzling flash” and a ground-shaking crack of thunder rattled out of the sky as the old man hit the ground.

Then and there, Lorena said, “I first knew terror.”

“I do not remember what my grandfather looked like, except that he had bushy white whiskers, but I can still see his shadowy form, so gigantic to a three-year-old, as he collapsed in the blinding light.” Loud noises or sudden flashes of light sent bolts of terror through her forevermore, whether it was Fourth of July fireworks or the flashbulb of a camera.

The arrival of her sisters, first Ruby and then Myrtle, went largely unnoticed in Lorena’s realm. Cows and horses, dogs and cats, and even her uncle’s pigs were the living things whose company she sought. “When I was hardly more than a baby I sensed the truth that an animal’s estimate of you is based on something deeper than what you look like, how you are dressed, or how you rate with your fellow humans,” she explained. Unlike other children, she did not feed her doll with a bottle, instead preferring to leave it in the pig trough to dine with the pink and squealing piglets. Dolls that were made to look like people were dull playthings, anyway, as far as Lorena was concerned. “A doll was just a doll,” she scoffed. “You couldn’t pretend it was anything else.”

Chapter 2

Around the age of five, Lorena began reluctantly to part the curtains of her small internal paradise and move into what she called “the other world—the world in which I was actually going to have to live.”

This world bore little resemblance to her private reality, for her father, Addison Hickok, was a man whose presence could darken the air in a room. Flashes of temper sizzled out of him as suddenly as the terrifying lightning strike that had felled her grandfather.

The first true human contact Lorena could remember was not a mother’s embrace, a grandparent’s lap, or a game of patty-cake with her little sisters. It was her father cramming her fingertips into her mouth and wrapping his own big hands around her head, forcing her jaws to clamp down over them until her cheeks were streaked with tears. She had been biting her fingernails; this was Addison Hickok’s way of breaking the toddler’s habit.

“There must have been times when he was not angry—times when he was gay, affectionate, even indulgent with us children,” she mused as an adult. “But I do not remember them.” Instead, she remembered the sounds of Addison’s horsewhip whistling through the air and cracking over the back of her collie pup. The dog had been chasing bicycles, and Lorena’s father had no more tolerance for a fun-seeking puppy than for a nail-biting child. That day, as she sat clutched in her mother’s lap listening to the little collie’s yelps and her mother’s sobs, was the first time in her four years on earth that Lorena knew anger.

Lorena’s fury toward her father would never fade. He was the sort of man who’d whip his daughters as readily as he’d whip a horse, or throw a chair after his wife as she fled the room, weeping. He fought with his employers, too, fights that often cost him his job. Judging by the number of times the Hickok family moved, Addison’s temper was notorious enough to blackball him in one town after another. “My childhood was a confusing, kaleidoscopic series of strange neighborhoods, different schools, new teachers to get acquainted with, playmates whom I never got to know very well,” Lorena recalled. By the time she was ten years old, she’d lived in ten different places across southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois.

No protection existed in the Hickok home when Addison was present. Lorena’s mother, Anna, rarely stood up to her husband. Anna’s meekness baffled her daughter. “I kept wondering, all through those childhood years, why my mother, who was a grown-up, too, and just as big as my father, let him do the things he did.”

Toward her mother, Lorena felt “a kind of resentful bewilderment.” Addison was forever beating Lorena and her sisters black and blue, whipping the pets Anna loved until they ran away, getting himself fired, and causing friction between his relatives and Anna’s. Yet anytime he went off to hunt for another job, a mission that could take days, weeks, or months, loneliness drove Anna to tears. The older Lorena got, the sorrier she felt for her mother. Even a child could see that Anna Hickok was a bitterly unhappy woman.

At the same time, an unspoken contempt tarnished Lorena’s feelings toward Anna. Lorena’s clashes with her father were more likely to trigger a scolding from her mother than sympathy. For Anna, it was simpler to blame Lorena for the beatings than to hold Addison accountable for his violence. The scoldings, with their implication that she was at fault, were worse for Lorena than the crack of a butter stave striking her legs and back. All her life, she would hate the sound of harsh voices.

Her sisters offered little solace or solidarity, either. They were so different, so cheerful and outgoing. Ruby in particular knew how to “get along,” to “play up” to the elders and somehow dance just out of reach of Addison’s discipline. She’d seemed to learn the knack of it without effort or guidance. Lorena’s inability to perform the same simple maneuvers was beyond Ruby’s understanding, and made Ruby resentful of having to witness Lorena’s increasingly harsh punishments. “Sometimes it would make me sick, and I couldn’t eat!” Ruby complained.

Perhaps even worse, Ruby and Myrtle were both as winsome as cherubs. “Nobody ever called me pretty or cunning, adjectives I was always hearing applied to my sisters,” Lorena mourned. In an era when daintiness was prized, she was tall and broad, with a face inclined to break out in a red rash at the slightest irritation. One night as her mother washed the supper dishes, Lorena overheard Anna speaking with pride about Ruby’s looks. Ruby had lovely golden curls, the precise opposite of Lorena’s straight reddish-brown hair.

“Crouching behind the kitchen door, I decided that the trouble with me must be that I was not a pretty child. What I needed, to get on in the world, was curly hair.” Lorena knew how to get it, too. She’d heard plenty of stories of victims of typhoid fever who’d had to have their hair cropped to keep it from falling out altogether. Often it grew back curly. So Lorena filched her mother’s sewing shears and carved out great chunks of her long, thick hair. Disaster ensued. Instead of transforming herself into a curly-haired angel, she succeeded only in looking like a boy. Then came the inevitable teasing.

“After a while I ceased being miserable about my lack of beauty, simply accepted the fact that I was homely, and did not expect admiration or compliments,” she said.

--

In a house where she bore the brunt of her father’s rages, where everyone but she was worthy of admiration and praise, Lorena came to the only conclusion that her young mind could piece together: something must be wrong with her, something that made her deserve such treatment. Once more, Lorena drew into herself, crafting an armor of the materials she had at hand—introversion and imagination. She craved “a kind of hiding place,” she said, “where I could relax and feel happy and contented, away from the frictions.”

Books formed the foundation of that refuge. Once she learned to read, Lorena’s world “became thickly populated and richly furnished.” Now she counted among her friends Ben-Hur, George Washington, the outlaws Frank and Jesse James, Black Beauty, the knights of King Arthur’s Round Table, and all the deities of Greece and Rome.

In her jungles and savannas, upon the ramparts of Troy and the battlefields of old Quebec, Lorena could be “happy and contented enough.” It wasn’t that she wanted to be apart from everyone else. Quite the contrary. “I desperately wanted to be liked, but I simply did not know how,” she said. “I was always in trouble. So I remained aloof, inarticulate, defiant, and, for the most part I daresay, thoroughly disagreeable.” The adults regarded her as “a queer, surly, unpromising youngster.”

Only one person had the power to coax Lorena into unlocking her imaginary gates and stepping into the world beyond: Aunt Ella. Ella Ellis was not an aunt at all, but rather Lorena’s mother’s cousin. Still, in terms of affection, Anna and Ella were more like sisters, and the children were told to call her Aunt Ellla.

The sound of Ella’s voice, soft and blessedly free of reprimands, enraptured Lorena the same way music did, embedding itself forever in Lorena’s memory. “Everything about her was exquisite” in Lorena’s eyes— her gentleness, her understanding, her daintiness. It was thanks to Aunt Ella that the Hickok girls were always well dressed enough to inspire envy in their neighbors. Every year a box arrived from Chicago, filled with the lovely clothes her daughter had outgrown.