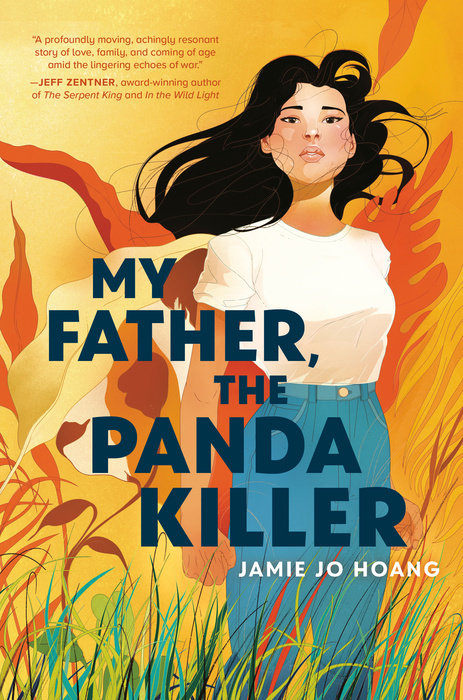

My Father, the Panda Killer

Author Jamie Jo Hoang

My Father, the Panda Killer

A poignant coming-of-age story told in two alternating voices: a California teenager railing against the Vietnamese culture, juxtaposed with her father as an eleven-year-old boat person on a harrowing and traumatic refugee journey from Vietnam to the United States.

“A profoundly moving, achingly resonant story of love, family, and coming of age amid the lingering echoes of war.” ―Jeff Zentner, award-winning author of The Serpent King and In the Wild Light

San Jose, 1999. Jane knows her Vietnamese…

A poignant coming-of-age story told in two alternating voices: a California teenager railing against the Vietnamese culture, juxtaposed with her father as an eleven-year-old boat person on a harrowing and traumatic refugee journey from Vietnam to the United States.

“A profoundly moving, achingly resonant story of love, family, and coming of age amid the lingering echoes of war.” ―Jeff Zentner, award-winning author of The Serpent King and In the Wild Light

San Jose, 1999. Jane knows her Vietnamese dad can’t control his temper. Lost in a stupid daydream, she forgot to pick up her seven-year-old brother, Paul, from school. Inside their home, she hands her dad the stick he hits her with. This is how it’s always been. She deserves this. Not because she forgot to pick up Paul, but because at the end of the summer she’s going to leave him when she goes away to college. As Paul retreats inward, Jane realizes she must explain where their dad’s anger comes from. The problem is, she doesn’t quite understand it herself.

Đà Nẵng, 1975. Phúc (pronounced /fo͞ok/, rhymes with duke) is eleven the first time his mother walks him through a field of mines he’s always been warned never to enter. Guided by cracks of moonlight, Phúc moves past fallen airplanes and battle debris to a refugee boat. But before the sun even has a chance to rise, more than half the people aboard will perish. This is only the beginning of Phúc’s perilous journey across the Pacific, which will be fraught with Thai pirates, an unrelenting ocean, starvation, hallucination, and the unfortunate murder of a panda.

Told in the alternating voices of Jane and Phúc, My Father, The Panda Killer is an unflinching story about war and its impact across multiple generations, and how one American teenager forges a path toward accepting her heritage and herself.

An Excerpt fromMy Father, the Panda Killer

CHAPTER 1

Jane

Angry. I’m angry that I’m thinking about my mom again. It’s the last thing I want to be thinking about. But here I am.

My mom left us when my brother, Paul, was three, almost four, or maybe he was four. Actually, he must have been four because the week after she left, he started preschool. Whenever I think about that week, I wonder what must have been going on in her head as she packed my lunch, knowing she wasn’t coming back. Did she think about us? Were we the reason she left? Was I not helpful enough, not smart enough, not clean enough? Did I need too much? Did I annoy her? Why was she so unhappy? Was it us? Did she not want to be a mother? Or was it something else or someone else? A scandalous love affair with some shop patron? If so, had I seen this man before?

Because the thing is, I never heard my parents fight.

They weren’t in love or anything stupid…

CHAPTER 1

Jane

Angry. I’m angry that I’m thinking about my mom again. It’s the last thing I want to be thinking about. But here I am.

My mom left us when my brother, Paul, was three, almost four, or maybe he was four. Actually, he must have been four because the week after she left, he started preschool. Whenever I think about that week, I wonder what must have been going on in her head as she packed my lunch, knowing she wasn’t coming back. Did she think about us? Were we the reason she left? Was I not helpful enough, not smart enough, not clean enough? Did I need too much? Did I annoy her? Why was she so unhappy? Was it us? Did she not want to be a mother? Or was it something else or someone else? A scandalous love affair with some shop patron? If so, had I seen this man before?

Because the thing is, I never heard my parents fight.

They weren’t in love or anything stupid like that. I didn’t grow up believing in fairy tales or princes or equality. My family is old-school—as in America in like the fifties, except it’s 1999. My father is the head of the household. He controls every aspect of our lives, from the finances to our daily schedules, and no one—not even my mother—ever argues with him. So, we might be American, but we’re certainly not Americanized.

Surprised. I was surprised she left. I am surprised. Not that she wanted to go or thought about it, but that she actually did it, and if I didn’t have a stomach full of resentment, I might have even admired her for it. But I was fourteen, and all I really felt was abandoned. Left to fend for myself and Paul at a time when my classmates were gushing about who might ask them to homecoming. The bitterness, even three years later, is strong. As for Paul, he was too young to really understand anything, so he probably assumes she died.

That day, the day she left, I knew something was wrong when my dad picked me up. My dad never picks me up from school. That he even knew where it was is perplexing. Since kin- dergarten, not once had he ever attended an academic function. Education was my mom’s domain. She never cared to check my homework or report cards; no, my enrollment was about being free of me for seven hours a day, five days a week.

My suspicions grew when he told me to walk to and from school for the next week. We didn’t live far, and to be honest, that was the greatest thing I’d ever heard. A full two miles to walk untethered to my parents? My preteen self did celebra- tory cartwheels all the way home. But this guttural, sinking feeling—intuition, I guess—was there also. I knew something wasn’t right.

To this day, I have no idea where Paul stayed during that first week. I just know that eventually, he came home. My dad must have closed up shop to come get me, but I couldn’t be entirely sure because he dropped me off at home alone and went back to work. I hate to say it, but my biggest concern at the time had been that I had no idea how long it would take to walk to school. It didn’t seem far, but having always been a passenger in the car, I couldn’t gauge the distance on foot.

What I did know was that I couldn’t be late. So, the next day, I woke up at 4:00 a.m., ate rice and eggs with scallion, made an American sandwich with bread, ham, and mayo, stuffed chips into my backpack, and left the house.

I sauntered past three blocks of apartments before reach- ing the busy Chapman Avenue, where I patiently waited for the white walk signal even though there weren’t any cars around. After the light, I continued past CVS Pharmacy, three small shopping plazas I hadn’t even noticed before, and McDonald’s. When I checked my watch, it was already 4:15 a.m. I picked up my pace but still felt like I was walking too slow. Valentino’s Pizza, aka the $7 pizza place, was so far away that I couldn’t see its signpost. My shins began to ache, and panic set in. Where was the park? Had I made a wrong turn? I hadn’t made any turns, so that wasn’t possible. Still, I doubted myself. The park that I thought was just around the corner was in fact seven stop- lights away. Images of Safeway, Del Taco, and the hot dog stand I’d wanted to try since it opened six years ago flashed through my mind. Immediately, I started sprinting toward school.

My heart was pounding, my legs felt weak, I couldn’t get enough air, and just before I thought I would pass out, a horn blared behind me.

Bleary-eyed, I looked over at the car and jumped away from the curb. It took me a moment to realize it was my dad. I don’t know when he woke up or how he knew where to find me, but there he was.

“What are you doing?”

I stared at him, dumbfounded. “I think I’m going to be late.” “Do you know what time it is?”

I shook my head. “Get in the car.”

I opened the door and climbed in.

“It’s only four-twenty-five in the morning. Why did you leave so early for?”

“Because I didn’t know how long it would take, and I didn’t want to be late.”

“How long you think it takes to walk to school?” I didn’t have a good answer.

It didn’t dawn on me then, but when I look back at that morning—and I look back pretty often—I’m fairly certain that my dad must have followed me from the moment I left the house. He must have lain awake while I got ready and waited for me to leave before tailing my every turn. Maybe he panicked when he saw me running. Maybe he thought I was running away. Maybe he thought I was leaving the same way my mother had.

But I wasn’t. The thought hadn’t even occurred to me. And actually, I find it insulting. I am not like my mother. I would never leave Paul alone with my dad. She is a coward. A heartless, non-motherly bitch who I swore would no longer occupy my thoughts. I wasn’t going to be like those weak-ass kids whose parents ruined them—who had to go to therapy because Mommy left. People leave, life is shit, and some of us don’t have time to sit on a couch and talk about our feelings.

Anyway, instead of driving me to school, my dad pulled into Callahan’s, a diner I hadn’t even known existed until we parked—and walked inside. We never ate American food. Maybe McDonald’s on the rare occasion my mom wasn’t able to cook, but never any food as fancy as Callahan’s. The booths were soft, faux leather, and there were packets of jam, salt and pep- per, three different kinds of syrup, saltine crackers, and sugar on every table. And there weren’t just a few booths either but rows and rows of them.

Once seated, I scanned the enormous menu. There were eggs and pancakes and waffles and burritos and ice cream sundaes.

“What do you want to eat?” my dad asked.

“I don’t know. What are you having?” Honestly, I was more concerned with the prices.

Everything looked good but also really expensive.

“I think I’ll have the steak and eggs,” my dad said, pointing to the picture. In my memory, his English is impeccable. I found the steak and eggs on the menu and checked the price: $12.99. So, I knew whatever I ordered had to be less than $12.99. That seemed easy enough.

When the waitress came over, my dad pointed at the picture, and I gave her my order. “I’ll have the pancakes and eggs.”

“Anything to drink?”

“Do you have beer?”

The waitress frowned, which in hindsight, isn’t at all unusual. Who comes to a diner at dawn with their daughter and orders a beer? But this is normal. Dad has a beer with every meal, and while he is a lot of things, he isn’t a drunk. “No, we don’t serve alcohol here,” the woman said. I wanted to punch her in the face. How dare she talk down to us like that? Who the hell did she think she was? A stupid, dumb waitress is what. Fuck her.

My dad, though, didn’t even flinch. He just said, “Okay, water then.”

“Same,” I cowered. “Nhà hàng này vắng huh?” I said, looking around at the empty restaurant.

“Because they don’t serve beer.” My dad laughed, echoing my thoughts. I laughed too.

The waitress rolled her eyes. “One steak and eggs and one pancakes and eggs coming right up.”

I’m ashamed to admit that I was so enamored by the biggest stack of pancakes I had ever seen that I forgot all about why we were there at 5:00 a.m. on a school day. The sweet, fluffy pile reached the edges of the plate and stood nearly four inches tall. My dad seemed pretty content too, so I’m not sure why between mouthfuls of pancake smothered in all three kinds of syrup, I decided to drop a bomb: “Is Mom gone?” As soon as the words left my mouth, I regretted them. We aren’t a family that discusses problems, and I was never included in any decision-making, ever. I shouldn’t have opened my mouth, but I did. Gripping my fork tight, I dropped my fist to the table and braced for impact.

“I think so.” He said this without any emotion, then took a gulp of water.

Did she take Paul? I wanted to ask. But I had already tiptoed so close to the line with my dad that I decided not to press it. Paul wasn’t with my dad when he picked me up, so I assumed she took him with her. He was her favorite anyway, being the boy and all.

“Okay,” I simply replied. And it was okay. Lots of kids got along just fine without a mom. We were a team now.

I think about that morning a lot, the morning my father followed me to school. Over and over again, I imagine him waiting for me to leave the house, watching me turn the corner, getting into the car, and slowly following me. One block, two blocks, ten blocks . . . past all the darkened landmarks, until he sees me running.

I think about this when I’m standing at the end of another beating I’m receiving for reasons I don’t fully understand. I play the moment over and over in my mind to soften and dull the pain. I do it because, in this memory, I know. I know that my father, for all his faults—and he has many faults—loves me.