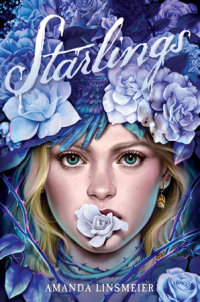

Starlings

In the wake of her father's death, a teen girl discovers a side of her family she didn't know existed, and is pulled into a dark—and ancient—bargain she is next in line to fulfill. A dark YA fantasy debut perfect for fans of House of Hollow and Small Favors.

Kit’s father always told her he had no family, but his sudden death revealed the truth. Now Kit has a grandmother she never knew she had—Agatha Starling—and an invitation to visit her father’s hometown, Rosemont.

And Rosemont is picture perfect: the famed eternal roses bloom all year, downtown is straight out of the 1950s . . . there’s even a cute guy to show Kit around.

The longer Kit’s there, though, the stranger it all feels. The Starling family is revered, but there’s something off about how the Starling women seem to be at the center of the all the town’s important history. And as welcoming as the locals are, Kit can’t shake the feeling that they're hiding something from her.

Agatha is so happy to finally meet her only granddaughter, and the town is truly charming, but Kit can’t help wondering, if everything is so great in Rosemont, why did her father leave? And why does it seem like he never wanted her to find it?

An Excerpt fromStarlings

chapter one

She was supposed to be dead.

That’s the big lie I can’t make sense of, and the closer we get to finally meeting her, the more nervous I become. I’ve traded a living father for a dead grandmother, and I still can’t wrap my mind around it. But there’s no time for that now.

We’re almost there.

My mom taps her fingers on the steering wheel to an old song, our car sagging with fatigue after delivering us from Callins, North Dakota, to the big woods of northern Wisconsin, miles of trees as far as my eye can see. Naked oak and birch and maple, pines standing proud and full, a dusting of snow everywhere, the buttery-pink rays of early light streaming through them.

It’s beautiful enough, but there’s still a part of me that wouldn’t want Hawaii, not even Florence or Cairo. There’s a part that only wants home. Wants to burrow under my bedcovers and escape reality in sleep. Sometimes I want to sleep forever so I don’t have to remember.

Swallowing the loss, I reach over and trace the papers tucked inside the door. A touchstone. The opening line to my dad’s last book, one he never finished:

We went into the sapphire water with our pockets stuffed full of jewels.

It’s embarrassing how often I say it to myself. In my head, out loud, under my breath. A good-luck charm, a mantra. An underlying question that might haunt me forever.

Why did you leave us?

And for the last couple of weeks, another thing I can’t stop wondering:

Why did you lie?

Sick of the snowy landscape whirring by, I lean my head back and close my eyes, thinking of stolen gems, and two ill-fated lovers on a ship, and a pirate’s rough laugh, and all the ways my dad brightened my world. My throat swells with the kind of pain that burns—sadness or rage, I sometimes can’t tell which.

My thoughts take me to places I don’t want to go, so I give up on thinking and open my novel to the page I dog-eared, glancing up to see a road sign.

rosemont 10 miles

“We’re close.” My mom’s tone is light, but her shoulders are drawn up; she’s escaping into herself. Anxiety is her shadow. I do what I can to help ease it, including trying never to add to it. The drive was difficult on her, but she only let me take over for a few hours. Despite the smile pulling at her lips, when she looks at me, sadness is tucked away in her gaze. I have her memorized: those eyes—the hazel of her irises, black pupils flowering in the centers—those high cheekbones, the blue floral tattoo winding up her forearm, her great laugh.

I hate that the pain in her eyes is familiar now. Resentment tugs at me. I return to the page, try concentrating on the fae lurking inside the story.

“How’s the book?” she asks.

“Really good,” I murmur. And it is. I just keep having to read the same lines over and over. Nothing is connecting in my mind. I won’t be able to relax until we arrive.

God, what will she be like?

“Seems like it’s taking you forever,” my mom says, interrupting my thoughts.

“You could’ve bought your own. . . .” I flip the page; the words swim.

“Why would we need two copies?” she asks. “Isn’t the best part of having the same reading taste that we can share books? We can’t share shoes, you know.”

“Well, you got skis for feet,” I answer.

“Ohh, hilarious.”

I snort, shut my book, trading reading for nothing.

“You okay?” Her worry pulls my attention.

I measure the expression in her eyes. Her pitched brows. Wish I’d kept reading, or at least pretended. “Yeah. I’m just nervous. You know.”

“I know.” She gives me a gentle smile as she turns onto a dark ribbon of a road. “She seems cool. I think we’ll like her.”

We pass underneath a canopy of trees politely inclining their heads above us, and drive toward a large, weathered wooden sign:

welcome to rosemont!

home of the eternal roses.

established 1781

population 2,089

We cross the town line as the morning light casts itself upon the sign. It’s so perfectly charming, I’m surprised that shit doesn’t sparkle. I face forward just as something runs in front of the car—a blur of an animal—a fox.

A cry. My mom swinging her arm against my chest instinctively, a seat belt of herself, as if I weren’t already wearing one. The brakes scream as the car swerves nearly off the wet road.

I wait for the beat of my heart to settle as it dawns on me, we’re fine. We’re fine.

I stare out the windshield, watch the fox dart away, blow out a breath. “Shit.”

Mom drops her arm and doesn’t correct my language. My parents always told me there were a lot worse words than curses: slurs, things that hurt people, ways you could make someone feel less than. Those were the ones I was taught never to say.

“We’re okay,” she reassures me, even as her hands shake.

“We didn’t hit it; it got away.” We both hate seeing animals killed, bloody bodies strewn along the pavement after meeting their unlucky fates with vehicles.

“It just rattled me.” Her breath comes out low and slow— one of her tricks. Sometimes it helps.

“I know we’re close, but can we get out for a minute?” I don’t wait for her to agree. My legs are aching; I need to move my body, and I know she’ll follow. It will calm her. I slip on my shoes, and she trails me out of the car, rubbing her bare arms.

We checked out of a motel super early, only a couple of hours ago, but we both stretch when we step onto the road. She shrugs her coat on over an original Nirvana tee—she has a deep and unending love for Kurt Cobain—while I hold my phone high, trying to catch a signal. Could I will the service to be less shitty? It’s been on roam for the last thirty minutes. But apparently it’s part of the charm, that Rosemont feels like another time entirely.

I stick my phone into my pocket and observe our surroundings.

Even with my mom having semi-prepared me, and a cursory Google search, I didn’t expect the outskirts of town to be so empty of anything but trees. They surround us, and to our right the woods are thicker, wilder, vast and unending. I’m following the line of tall trees up to the brightening sky when something catches my eye: a cloud of birds.

My mouth goes slack as they start to chatter, because of all the things . . . it had to be this?

“Mom.” I point out the birds in flight, voice strained. “Starlings.”

Our namesake. But even more. We watch the flock move, growing louder, swooping in formation across the watercolor sky, diving here and there. Our eyes connect, and I can tell that her heart is pierced like mine; I know what she’s thinking of, what we’re both remembering now: that hot day in August. The starlings didn’t dance in the air then. They perched in the branches and cried.

Our skin sticky under those black dresses, our clammy hands squeezed together, and the starlings—dozens, hundreds, maybe thousands, crying in the trees, mourning when I couldn’t.

Breaking the memory, my mom steps closer to me, whispers, “A murmuration.”

This is the third noteworthy time I’ve seen starlings. The first, when I was seven—then it was beautiful, strange. The second time at the funeral, just four months ago. And now. But in this moment, it only leaves a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach. We watch the birds until they drift out of sight. Silently we look at each other, return to the car. I click my seat belt into place. Why them? Why now?

“At least the fox is okay.” Her smile is wobbly as she turns the key in the ignition, then pauses. “I think it was a fox anyway. You good?”

No! I’d like to scream. No, no, no. I’m not good. I’ll never be good again.

I nod. “I’m fine. Let’s go.”

As she drives, I fiddle with the Bluetooth, the music all garbled and fuzzy. I switch to the radio, but it doesn’t sound any better. With an annoyed sigh, I turn it off. Pull my messy bob back into a knot, just to have something to do with my hands, twitchy because we’re here. Almost. I’ve replayed this meeting in my head several times, and I still don’t feel prepared to meet my grandmother Agatha. Why didn’t she ever reach out before? Will we like each other? Will we laugh about my dad? Cry about him? Will she tell us all the truths he couldn’t?