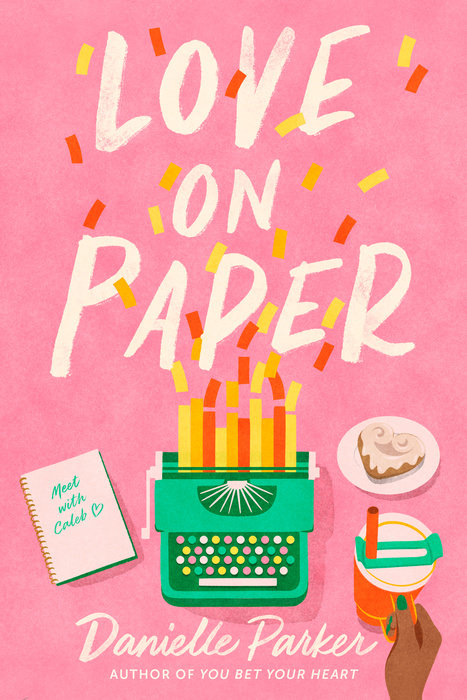

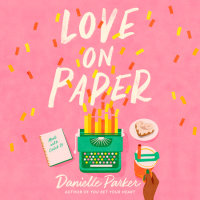

Love on Paper

An ambitious teen novelist must play nice with her talented—and annoyingly handsome—rival at an exclusive writers’ retreat in this heartfelt romance from the author of You Bet Your Heart.

“Moving and memorable. A book you’ll want to return to again and again.” —Kristy Boyce, bestselling author of Dungeons and Drama

Macy Descanso is a writer. Who cares if her bestselling-author mother pulled some strings to get her into a prestigious writing retreat? Macy belongs here. Even when the coordinators unexpectedly announce that this year’s theme is romance, Macy—a total cynic—is up for the challenge.

But she’s not prepared for her critique partner to be fellow publishing nepo baby Caleb Bernard. While Caleb may be what most romance writers would describe as “swoony,” he’s off-limits, because the Descansos and Bernards have beef.

With a chance at publication at their fingertips, though, Macy and Caleb have to put aside their issues. But is four weeks enough time to fight through writer’s block, step out of their parents’ shadows, and find the courage to create their own love story?

An Excerpt fromLove on Paper

Chapter One

To be a writer, you need to (a) write and (b) have something to write about.

Or so I’ve been told.

Allegedly.

Perhaps.

Maybe you’re like me—an aspiring writer who is afraid to actually write and unsure if what she has to say is even worth saying, so you’re kinda stuck on this wheel, going around and around, wanting to write but afraid to actually do it. A great conundrum, if you will.

“Macy, hello? I said we’re here.” Dad’s baritone transports me back to the actual moment, not the obligatory freak-out happening inside my head.

We’re here.

“Here” meaning Penovation in Berkeley, California, one of the nation’s most prestigious writing retreats, where I plan to spend the next four weeks.

That is, assuming I get out of the car and, you know, step onto the Berkeley Creative Arts College campus. I bite my bottom lip, tasting the Fenty Heat gloss as my brow furrows.

“I know that look. What’s on your mind?” Dad shifts in his seat and turns off the car. My eyes are more interested in the busy parking lot, where families are offloading young aspiring writers and their bags.

What isn’t on my mind?

I can’t quite answer Dad’s question.

Not yet. I’ll make a note to circle back in four weeks.

He rolls down the driver’s-side window, and a soft breeze cools the uncertainty building in the car and in my chest. My gaze shifts to the entrance of the campus, where several eucalyptus trees, which must be at least a hundred years old judging from how they reach toward the sky and sway ever so lightly, providing nice added detail to the forest motif that nature has graciously gifted us.

If I get out of the car, if I allow myself to do this, I know I’ll be steeped in Bay Area beauty and I’ll get to try something I finally think I have the courage to do.

That’s a big if, though.

“Aren’t you excited to be at camp? Getting accepted is quite an honor. I would be thrilled.” Dad pauses, savoring his own words. “Or is there something else?”

“First off, it’s a writing retreat. Not camp.”

“Oh shoot! Sorry—you’re right. If there was ever a time and a place that semantics mattered, it would be now.”

“I mean, this is campy, but it’s not camp. You feel me?”

Dad lets out a soft chuckle and briefly closes his dark brown eyes while throwing an index finger in the air, his favorite move when he’s tickled. “I don’t, but perhaps it’s not for me to understand.” Dad pauses for a moment, then dives back in. “It’s okay to be nervous, you know. Actually preferable. The nerves will do you good. You’ve got this, Macy.”

As fast as my brain rushes to envision the worst-case scenario—me being unable to write a single word at this retreat—I challenge myself to envision the best-case scenario: me writing lots of words, even good words, that when strung together make something special.

Especially since Mom let it slip (translation: she told my dad during one of her tirades about my “life choices” and “the teen agenda”) that she had to gently persuade some of her bookish friends to give my application another look.

The writing samples required for this retreat were so lengthy and over-the-top that most students who saw what was expected to just apply quit before they even started, exercising their better judgment and choosing to lean into being young and on a beach or whatever. I, however, pushed along and wrote what I thought was a solid essay. Only to find out Mom ran a workshop at UCLA two summers ago with one of the current lecturers and casually dropped my name and casually mentioned that perhaps my analysis of Their Eyes Were Watching God wasn’t astounding, per se, but that I had a lot of potential, a lot of talent waiting to be unleashed if I could just get into this program. I can imagine my mother batting her unfairly long eyelashes and saying, Give my daughter a chance. Pretty please with a cherry on top.

Did Mom have to mention all that to Dad, who can’t keep a secret to save his life? No, but she did anyway. They’re divorced but love to get together to chat about me. Kinda rude.

Was she wrong about my essay? Also, no. It wasn’t my best, but it wasn’t my worst—that would be all of freshman year, when I only wrote in third person because . . . honestly, I can’t remember why, but I’m glad I stopped.

But do I want to admit that sometimes I write things that seem average to my way-above-average writerly parents? Would they even understand what it means to be just moderately talented? Dad is a well-known author of a beloved children’s book, and Mom is famous for her literary fiction—like gets-stopped-in-the-supermarket-and-gawked-at, her-books-are-in-airport-bookstores kind of famous.

Outside of our car, it’s hard not to notice the commotion that begins to swell. More writers and their parents pull up, and with them comes the reality of the situation that it’s time to say goodbye.

“Is this hesitancy about your mom?” Dad gets very after-school special; he leans in close, and his eyes soften.

“Oh gosh, not now—”

“I know that the two of you . . . your relationship has never been easy—”

“It’s fine. Really.” I’d rather do anything else than have this conversation. I get how lucky I am to have my parents’ help, but sometimes, as in this case, when everyone thinks they know your mom and dad because they know their work, they assume they know you. And that is not reality.

Dad is my favorite person in the world, and even when I want to be mad or a smart-ass in front of him, I can never fully commit to the bit. What would be the point? I’m extra, but I’m not that extra. If anyone knows when to call me on my antics with a laugh or an eye roll, it’s Dad.

“Okay, you’re right. We don’t need to have this conversation now. But we will . . . eventually. You can’t escape what you’re feeling forever, Macy Mariah Bak Descanso. She’s your mother, after all.”

Ugh. Dad using my full name. If he weren’t my main parent, my ride-or-die since he and Mom got divorced when I was three, I would be annoyed with him and his questionable advice. But I know it’s who he is. Dad believes in processing.

These parenting conversations never embarrass him. For some reason, turning twelve and starting my period comes to mind. Mom wasn’t around when it happened, so he got me a pink cake with way too much frosting, and a bottle of Martinelli’s apple cider. Then he called my aunt Tammy to have that conversation with me while he went to Target to get an ungodly amount of pads and tampons that overfilled the hallway closet. If anything, sometimes Dad wants to talk and share a little too much. One day I’ll need to tell him that some things should be left to teen hearsay and the internet—a girl’s gotta figure some things out on her own.

“Let’s get you checked in,” he says eagerly. “You’ve got authors to discuss, worlds to bring to life. Forget how you got here. Writing your magnum opus or the next great American novel is top priority.” He winks, and I wink back, acknowledging a little inside joke we share about who and what is considered literary greatness.

As much as I’m afraid that I’ll be judged by who my parents are, I have to remember that this is my reprieve. No distractions.

My fingers fiddle with the door handle. I could stay in my dad’s Lexus, and we could talk for hours, as we’ve done so many times before. But something inside me forces me to move. Slowly, I open the door.

To be a writer, you need to write. Or maybe you just need the opportunity to prove to yourself, and possibly your super-intense mom, that you can measure up. That you belong at one of the country’s best writing retreats. That your story matters.

Chapter Two

We stand outside the dorm, a tall light grayish building with an assortment of flags decorating the windows. Dad gives me an ultra-tight hug, and as his eyes begin to mist, I hit him with a squeaky, almost childlike “Daaaaaaaaaad.”

He dabs the corners of his eyes and straightens. “Okay, okay. It’s just that—”

I know where this is going, and I cannot have any waterworks in public. My voice gets stern, and I age twenty years in an instant. “DAD.”

“You’re right. Four weeks is a long time apart, though, isn’t it? No, this is good. We are both doing things that’ll help us learn and grow as individual beings, and I am grateful for these opportunities.” He closes his eyes.

“Yes, same, but way less wordy. We’ll be fine.” I grab the handle of my yellow wheely suitcase. Around us, students are heading through the dorm’s double doors. No one else seems to be having this type of emotional moment with their parents. They all sort of fly the coop. Or maybe they aren’t first-timers, like me. But this is on-brand for Dad. He’s very in touch with his emotions—most starred reviews of his books say so.