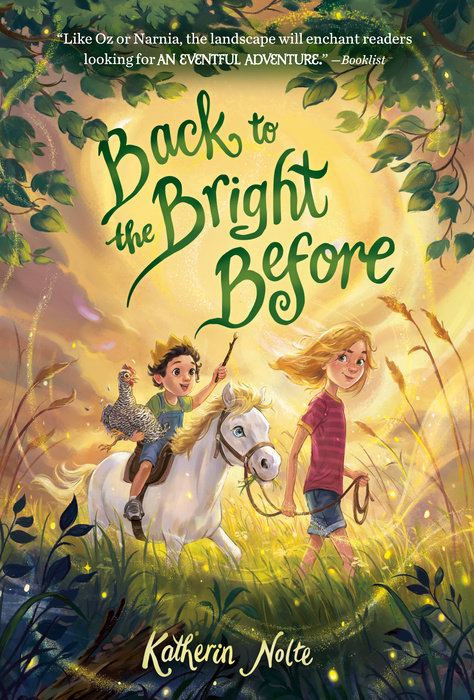

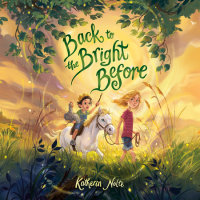

Back to the Bright Before

Author Katherin Nolte Illustrated by Jen Bricking

Back to the Bright Before

A magical adventure about two brave siblings determined to find a treasure that could save their family -- now in paperback!

When eleven-year-old Pet Martin’s dad falls from a ladder on their family farm, it isn’t just his body that crashes to the ground. So does every hope her family had for the future. Money is scarce, and Pet’s mom is bone-tired from waiting tables at the local diner, and even with the extra hours, it’s…

A magical adventure about two brave siblings determined to find a treasure that could save their family -- now in paperback!

When eleven-year-old Pet Martin’s dad falls from a ladder on their family farm, it isn’t just his body that crashes to the ground. So does every hope her family had for the future. Money is scarce, and Pet’s mom is bone-tired from waiting tables at the local diner, and even with the extra hours, it’s not enough for a third surgery for Pet’s dad. Her five-year-old brother, Simon, now refuses to say anything except the word “cheese.” Worst of all? The ladder accident was Pet’s fault.

She’s determined to fix things—but how? Good old-fashioned grit…and maybe a little bit of magic.

When a neighbor recites a poem about an ancient coin hidden somewhere on the grounds of the local abbey, Pet forms a plan. With her brother, a borrowed chicken, and a stolen pony, Pet runs away from home. If she can find the coin, Daddy can have his surgery, Momma can stop her constant working, and Simon might speak again. But Pet isn't the only one who wants the coin…which means searching for it is more dangerous than she ever imagined.

This dazzling debut novel filled with magic, family, and adventure is sure to be an instant classic.

An Excerpt fromBack to the Bright Before

Chapter 1

I didn’t scream when Daddy fell from the ladder. My mouth opened, my throat became tight, but I was as silent as our woodpile when his body tumbled to the earth. And he did tumble--like an acrobat, end over end, his giant form arcing in slow motion toward the ground.

“Impossible,” Momma said later, when she asked me to tell every single detail of what had happened. “People don’t fall in slow motion from the sky.”

But he did.

I saw him. I’m eleven years old, which, trust me, is old enough to know fact from fiction.

“Unbelievable,” said Momma when I told her how, right before he hit the ground, his body straightened into a horizontal line and floated like a feather. “Two-hundred-pound men don’t drift like feathers when they fall.”

“Well, Daddy did,” I said. “I saw him.”

Momma gripped her coffee cup. She was sitting at the kitchen table. Mascara was smudged around her eyes because she’d been crying. It was midnight. Simon was in bed. I should have been…

Chapter 1

I didn’t scream when Daddy fell from the ladder. My mouth opened, my throat became tight, but I was as silent as our woodpile when his body tumbled to the earth. And he did tumble--like an acrobat, end over end, his giant form arcing in slow motion toward the ground.

“Impossible,” Momma said later, when she asked me to tell every single detail of what had happened. “People don’t fall in slow motion from the sky.”

But he did.

I saw him. I’m eleven years old, which, trust me, is old enough to know fact from fiction.

“Unbelievable,” said Momma when I told her how, right before he hit the ground, his body straightened into a horizontal line and floated like a feather. “Two-hundred-pound men don’t drift like feathers when they fall.”

“Well, Daddy did,” I said. “I saw him.”

Momma gripped her coffee cup. She was sitting at the kitchen table. Mascara was smudged around her eyes because she’d been crying. It was midnight. Simon was in bed. I should have been in bed, too.

“Get out of here, Pet,” she said, voice shaking. “Your lies are making me want to smack you.”

I will tell you three things. My name is Perpetua. I do not tell lies. And I was very much happy to oblige.

“That must have been a horrifying experience” is what Sister Melanie said when I told her about Daddy’s fall--which was much better than being told you were an impossible, unbelievable liar.

“Do you believe me?” I asked after describing how first he tumbled, then he floated before hitting the ground. It was always hard to tell what Sister Melanie was thinking. She spoke carefully, like each word cost her a nickel and she only had a few quarters in her pocket.

“Of course.”

I looked at her. She was the youngest nun in the convent, only twenty, and she had long black hair that she wore in two braids, and equally dark eyes. On her pale face was a pair of bright red glasses.

“I didn’t think nuns could wear red” is what Momma had said when I told her about Sister Melanie’s glasses.

“Why not?” I asked.

“It has to be against one of their rules. They’ve got a whole dictionary’s worth of them.” Momma waved her bottle of glass cleaner dismissively. She was dusting the TV. Simon always smudged it because he thought he could feel people’s hair if he ran his fingers across the screen. He never could, of course, but he kept on trying just the same.

My momma doesn’t know much about nuns--and that’s not an insult. Just a fact. She’s never walked down the gravel road with Simon and me to visit the abbey, so why she thought there was a rule against nuns wearing red glasses was anybody’s guess.

I didn’t try to correct her, though, because she was in one of her moods, and the look on her face as she scrubbed at that TV screen was one baby step shy of furious.

There was a part I left out when Momma asked me to tell her second by second how my daddy fell. I didn’t lie about what happened, but what I did was start the telling after the most critical detail. I didn’t tell this fact to Sister Melanie, either. That’s because I’m proud--not of what happened--no, most certainly not--but just . . . proud. I’m smart. I can do one hundred multiplication problems in one minute, twenty-eight seconds--the fastest in my class. I’m strong. I carried Simon home from the nuns once, when he fell and scraped his shin and made a big show about not walking home, plopping down, toad-like, in the middle of the road. Well, I swung Toad Boy onto my back and carried him the three-quarters of a mile to our fence. I’m tall, which is good for reaching things, and I’m skinny, which makes slipping through cracks easy. I love my freckles and my long hair--strawberry-blond, everyone calls it.

So, see, I’m proud--and when you’re proud and you make a giant mistake, you don’t want anyone to know. When you’re proud, failure is the bitterest fruit you can bite.

That’s why I didn’t tell Momma or Sister Melanie what I did. But I’m going to tell you.

Some of what happens in this story might seem unbelievable. The things Simon and I saw, what we did, what we found--you might wonder if it’s really true. That’s why it’s important you believe me. You have to know in the hot, beating center of your heart that Perpetua Martin doesn’t lie.

So here goes.

It was my fault Daddy fell from the ladder. His getting hurt--and everything that came after--was all because of me.

It was a Saturday in November. The sun was shining. The air was warm. The wind was whirling leaves into miniature tornadoes. Daddy was cleaning the gutters on our farmhouse. I had the camera Nana sent me from California. It was two days past my birthday, and I was itching to try it out.

“Daddy, look down here,” I called up to him. Simon was beside me, of course. He’s always beside me, like a piece of gum that no matter how much you scrape, you can’t get off the sole of your shoe.

“Hold your horses, Pet,” Daddy said in his big, booming voice. Everything about my daddy was big--his six-and-a-half-foot body, his dark, bushy beard, the waves in his hair. “Your dad looks like a lumberjack,” kids at school said, trying to be mean, but I always took it as a compliment.

“Please,” I cried, “just for a second--look. I want to take your picture.” I haphazardly pointed the camera up at him. Really, I had no idea how to use the thing. It was fancy, with a big flash on top and a lens almost as long as a telescope.

“Ridiculous,” Momma had said when the camera arrived in the mail. “To send a child a five-hundred-dollar camera. What was she thinking?”

There was a note in the box, on a square of scalloped ivory-colored stationery:

Dearest Perpetua,

May this lens be a window to a larger world. Happy birthday.

Fondly,

Nana

I had never seen or even spoken to my nana. Nobody in my family had since before I was born. She was my sole living grandparent, but she was so absent, she might as well have been a ghost. Except on birthdays. Every year, she sent Simon and me an expensive gift with a cryptic phrase on a piece of scalloped stationery. Her extravagance drove Momma nuts. Daddy didn’t care, though. He never let Nana bother him.

“Say cheese,” I said to Daddy, atop his ladder. “Say cheese, please.”

Then Simon picked it up. “Cheese, please! Please, cheese!” he cried like a parrot.

Finally, Daddy looked. He turned his head, high above me, and even though he was so far away, up against the pale November sky, I could see his smile.

“Cheese!” he boomed, his voice a cannon blast.

And that’s when that awful wind whipped, the ladder tipped, and Daddy began to somersault through the air.

Chapter 2

Simon didn’t talk after that, which was a shame because I had taught him some pretty cool words. Even though he was only four, he could say indubitably, exuberance, and ex nihilo. (And because I want to prove to you that I don’t lie, I’ll tell you this: That last part is Latin, and I only know it because Sister Melanie taught it to me.)

So Simon turned silent--except for one word. One word he said in reply to everything. Cheese.

Sometimes it was appropriate, like when I asked, “Simon, what would you like to eat?”

“Cheese.”

Sometimes it was annoying, like when I said, “Simon, pick a number between one and ten.”

“Cheese.”

And sometimes it was ridiculous. “Simon, what would you like for Christmas?”

“Cheese.”

At first, Momma thought it would pass. “He’s just upset is all,” she said, smoothing his dark hair off his forehead as she tucked him into bed.

“Cheese,” Simon said from beneath his dinosaur sheet, as if agreeing with her.

But as the months went by, and Daddy remained all broken in bed, and the only sound that ever came out of my brother’s mouth was a six-letter word from the dairy case, she got worried.

“What a mess,” she’d mutter when she got home from a double shift at Carlton’s. Momma was a waitress. With Daddy in bed, unable to work, she had started waiting tables from breakfast till close, trying to make up the difference. By the end of the night, her feet were as swollen as balloons. “What a big, fat, giant mess.”

She looked at the house, at the dishes in the sink, the toys on the floor, the stack of bills on the table. Yes, the house was a mess. But she meant more than that, too.

“I’ll fix it,” I told her. It was way past my bedtime. I should have been asleep hours earlier, but Momma had stopped noticing things like bedtimes after Daddy fell. So I stayed up late because I could get away with it.

Momma snapped her head around, quick and angry as a snake. “How are you going to fix it, Pet? Huh? What on earth could you possibly do to fix everything that’s wrong?”

I shrugged. “I’ll just fix it.”

“Great. Good to know, Little Miss Fix-It. Well, you can start with your brother. Teach him to say something besides cheese.” She stormed out of the kitchen, her reddish-blond ponytail swinging behind her.

Momma was often mean and short-tempered now, but she hadn’t always been that way. The two of us used to have the most fun together, especially in her garden. You know how some people have a green thumb? Well, my momma had a whole green hand. She could grow anything with water, sun, and a little bit of patience.

Her garden, let me tell you, was my favorite place to be. Back behind the house, the two of us would work, three seasons out of four. In the spring, I’d help her plant; all summer we’d crawl on our hands and knees, fighting weeds and picking produce; in the fall, when the harvest was over, we’d spread mulch; and winter would find us side by side at the kitchen table, studying seed catalogs and dreaming of next year. Yes, I was Momma’s right-hand girl.

How I wish you could have seen it: everything so bright and green, row after row. Kohlrabi, lettuce, strawberries, carrots, potatoes, onions, cantaloupes, pumpkins. My momma grew it all. And I helped her, every step of the way.

But then Daddy fell, and that winter when I showed Momma the seed catalog that had come in the mail, she wouldn’t even look at it.

“Not this year, Pet,” she said, and shook her head.

“But, Momma,” I said, “we’ve got to plan. Spring will be here before you know it.”

We were in the kitchen. Momma turned her face toward the window, with its view of the backyard, where her garden lay, brown and bare. “I don’t have time anymore. Besides, something tells me spring is a season of the past.”

So we didn’t plan. And we didn’t plant. Instead of having peas from our own yard, we ate them microwaved from a can. That big rectangle out back, which used to be a living, breathing garden, just sat there, unloved and dead.

I tried not to look in its direction.

And now, instead of being Momma’s right-hand girl, I was just a bother. No matter what I did or said, it was wrong. I was always in her way. But I didn’t hold it against her. She deserved to be mad at me. It was all my doing: her aching feet and Daddy’s busted body. All because of me and my camera.

Mea culpa.

That’s some more Latin that Sister Melanie taught me. It means “my fault.”

I am guilty.

Chapter 3

I’ll tell you how I met Sister Melanie, since you’re probably curious. I know it’s kind of unusual for an eleven-year-old to be friends with a nun.

Well, I met her at the start of last summer, before Daddy fell. School was out, and I was walking down the gravel road, kicking up dirt and looking for toads, with nothing very interesting to do.

That’s when I saw a teenager planting flowers by the side of the road. She had on blue jeans, a bandanna, and red glasses. I stopped to watch her.

After she’d finished digging the hole she was working on, she set down her spade and looked up at me. “Salve.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“It means ‘hello,’ ” she said. “It’s Latin.”

“Oh. I’ve never met anyone who speaks Latin.”

The teenager laughed. “Neither have I.”

“Why are you planting flowers here?” I asked.

“This is where I live,” she said.

“On the side of the road?”

“No. Here.” She pointed at the metal sign behind her that said Our Lady of Perpetual Help Abbey.

Now, I have to tell you, I’d seen that sign my whole life, but that was the first time I actually saw it, with my mind and not just my eyes.

“My name’s on there,” I said, sort of aghast.

“Really?” said the teenager.

“I’m Perpetua.”

“Then you are perpetually Perpetua. How exquisite.” She stood up and offered me her dirt-covered hand. “I’m Sister Melanie.”

“Are you a nun?” I know I sounded shocked, which is rude, but I’d never actually seen one of the nuns before. It was kind of like meeting a fairy.

“God willing.” She picked up her spade and the empty plastic flower containers. “Perpetua, I must be going, but it was a pleasure to make your acquaintance.”

“Wait.” I didn’t want her to leave just yet. “What’s the word you said, that means ‘hello’?”

“Salve,” said Sister Melanie.

“Salve,” I repeated. I liked how it felt, kind of mysterious, on my tongue.

Sister Melanie must have known what I was thinking. “I could teach you some Latin, Perpetua, if you’d like.”

“I’d like it very much,” I said.

Sister Melanie smiled. “Then come back tomorrow, and we shall commence. Vale, Perpetua.”

“Goodbye, Sister Melanie.” I skipped off down the road, pleased to have figured out what vale meant.

So that’s how it started: both my friendship with Sister Melanie and my love of Latin. Every week, she taught me a new phrase, and I spent the next seven days letting it roll around in my head. Once I’d known her for a year, that meant I could say fifty-two things.

Fifty-two might seem like a lot, but really, it’s only the beginning when you think about all the things in the world that must be said.