Part I

Chapter 1

Origin Story

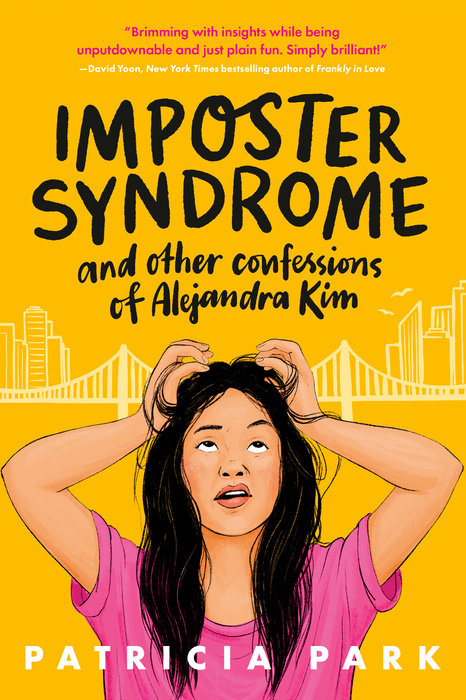

When you have a name like Alejandra Kim, teachers always stare at you like you’re a typo on the attendance sheet. Each school year, without fail, they look at my face and the roster and back again, like they can’t compute my súper-Korean face and my súper-Spanish first name. Multiply that by eight different teachers for eight periods a day, and boom: welcome to my life at Quaker Oats Prep.

I mean, Alejandra is like the “Jessica” of Spanish girl names—basic as all hell. It’s not like my parents named me Hermenegilda or Xóchitl. And yet people still find a million and one ways to butcher my name. I’ve been called:

1. Alley-JOHN-druh

Mr. Landibadeau, our college guidance counselor, who apparently never took Spanish 101. (Hello, the “j” is pronounced like an “h.”)

2. Alexandra

Mr. Schwartz, sophomore year, who ironically “Ellis Islanded” me even though he teaches US history.

3. Ah-leh-CHHHHHAN-durah!

Ms. Sanders, junior year physics. Technically this is correct—the third syllable is pronounced like the “Chan” in “Chanukah.” (Hanukah? Hanukkah? You get my point.) But Ms. Sanders was trying so hard to…

Part I

Chapter 1

Origin Story

When you have a name like Alejandra Kim, teachers always stare at you like you’re a typo on the attendance sheet. Each school year, without fail, they look at my face and the roster and back again, like they can’t compute my súper-Korean face and my súper-Spanish first name. Multiply that by eight different teachers for eight periods a day, and boom: welcome to my life at Quaker Oats Prep.

I mean, Alejandra is like the “Jessica” of Spanish girl names—basic as all hell. It’s not like my parents named me Hermenegilda or Xóchitl. And yet people still find a million and one ways to butcher my name. I’ve been called:

1. Alley-JOHN-druh

Mr. Landibadeau, our college guidance counselor, who apparently never took Spanish 101. (Hello, the “j” is pronounced like an “h.”)

2. Alexandra

Mr. Schwartz, sophomore year, who ironically “Ellis Islanded” me even though he teaches US history.

3. Ah-leh-CHHHHHAN-durah!

Ms. Sanders, junior year physics. Technically this is correct—the third syllable is pronounced like the “Chan” in “Chanukah.” (Hanukah? Hanukkah? You get my point.) But Ms. Sanders was trying so hard to sound muy auténtica, which was almost as bad as if she’d just Ellis Islanded my name in the first place. You know, like those annoying people who go to a bodega and order a “CWAH-sson,” when the rest of us commoners just say, “cruh-SAHNT.”

But if you’re the one ordering croissants from a corner bodega, that’s the least of your pretentious problems.

For the record, I just pronounce it “Ah-lay-HAHN-druh.” But I usually tell people to call me “Ally.” I say it the easy gringo way: “Alley.” As in, alley cat, alleyway, back-alley. That’s what everyone at Quaker Oats Prep calls me.

Our school’s not actually named Quaker Oats. It’s officially Anne Austere Preparatory School, named after a Quaker from the 1600s who was literally burned at the stake for trying to better humanity. But everyone just calls us Quaker Oats. We’re not like Brearley or Chapin or Dalton. We’re more “progressive” (read: “hippie” and “weirdo”). We’re like the minor leagues for the big Quaker colleges like Whyder and Swarthmore and Bryn Mawr. Laurel Greenblatt-Watkins, my first and best friend here, says we’re a hotbed of granola crunchiness in the middle of Chinatown. I don’t know what to think. I’m just a scholarship kid (90 percent). And Ma never lets me forget about that 10 percent we owe each year.

Back in my neighborhood in Queens, they call me “Ale.” Except when Ma gets súper pissed, then it’s all, “Alejandra Verónica Kim, ¡andate a tu cuarto!”

Papi always used to call me “Aleja-ya.”

If I were Dominican or Puerto Rican or Colombian or Mexican, then at least I’d have some solidarity in New York with “mi gente,” my people. Which might sound vaguely racist, but it is what it is. But my parents are Argentine, and there aren’t a whole lot of us here. Both sets of my parents’ parents were Korean immigrants who were aiming for America-North back in the day but washed up in America-South.

Sidebar: the Korean name for America is Mi-Guk—Beautiful-Country. For South America, it’s Nam-Mi—South-of-Beautiful. Which is all kinds of linguistically fucked up.

It sounds random, how a bunch of Koreans ended up in Argentina. The short answer is immigrant labor exploitation. They were sent over to farm and “populate” Patagonia, but the land was basically a barren desert. The Koreans were like, yeah, nope, and hightailed it to Buenos Aires, where they settled in a villa miseria called Baekgu and sewed clothes all day.

Every time I get upset about something first-world, like how they forgot the ketchup packet with my fries, I have to stop myself and remember: Papi grew up in literal miseryville. He worked in a sweatshop, forced into child labor by his own parents.

That’s what happens when you’re the kid of immigrants: your whole life is one big guilt trip.

Nothing about my family is “normal.” Not even the Spanish we speak, which is all weird and Porteño—aka Buenaryan. Apparently there’s a hierarchy within the Latinx community, where everyone thinks Argentines are snobby, white European wannabes looking down their noses at the rest of Latin America with their hoity-toity accents and weirder verb conjugations and stubborn refusal to use normal words like “tú”—you. Instead Argentines say “vos,” which was súper trending in Spain in the 1500s but has since fallen the way of the pay phone and the postage stamp.

Also, Argentines use the word “che”—hey—a lot, which is how Ernesto Guevara got his nickname.

Anyway, Ma and Papi knew each other as kids back in Baekgu, but they re-met here in New York as adults, and the rest, as they say, is historia.

Che, that was exhausting. What’s kind of annoying is how people—adults especially—always expect you to lead with your Origin Story like you’re in a Marvel comic, sans the superpowers. Like, ooh, tell me the exotic story behind your name/face/race/peoples. Walk me through that radioactive spider bite that transformed you into the Super Freak you are today. (Peter Parker, by the way, is also from Queens.)

I am 94.7 percent sure they wouldn’t do that if I looked like my ancestors had stepped off the Mayflower.