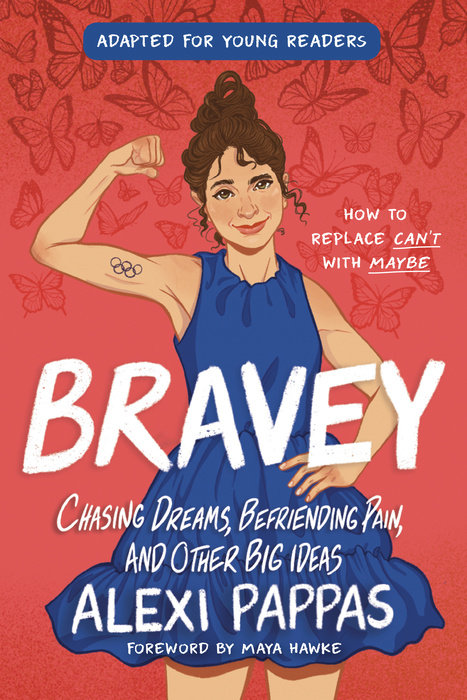

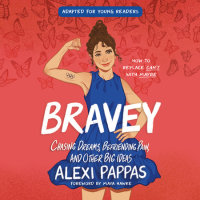

Bravey (Adapted for Young Readers)

Alexi Pappas is not only an Olympic runner, actress, filmmaker, she is a writer whose heartwarming and life-affirming memoir will inspire young readers, as she shares the touchstone moments in her life that helped her learn about confidence and self-reliance, compassion and forgiveness, and loss and hope, in this accessible and motivating memoir.

What is a bravey? For Alexi Pappas, it means to chase the goals that seem scary. She has not shied away from the challenge.

In this honest and hopeful memoir written especially for young readers, Alexi Pappas details key moments that had profound effects on her life, including the loss of her mother when she was just four years old, to her formative years at school where she felt different from her peers, and into her young adult life, including the incredible year she experienced in 2016 when she made her Olympic debut as a distance runner and wrote, directed, and starred in her first feature film. Through it all, Alexi worked hard—physically, mentally, and emotionally, but not without setbacks and difficulties, all of which helped her learn about confidence and self-reliance, compassion and forgiveness, loss and hope. Even with good things happening, Alexi found herself facing anxiety and mental health issues. Isn't winning supposed to make a person happy? How does one make life better when it already seems good? Alexi doesn't provide all the answers, but she offers ideas to consider when life gets complicated.

Young readers will be inspired by Alexi's journey to create an abundant life filled with loving friends and family and strong female role models and mentors--who helped to shape the bravey she is today.

An Excerpt fromBravey (Adapted for Young Readers)

MY PAL, PAIN

Braveys: Whatever challenging feelings you’re holding right now, I promise they are not forever. This is both a good thing and a hard thing. It’s hard because sometimes, we feel amazing and we never want that to change. Wouldn’t it be awesome for life to always feel as exciting as it does when you go to school on a Friday knowing you’re sleeping over at your best friend’s house that night? But that isn’t the way life works. Time always carries us forward, and it can be sad to watch good things fade and change. But this also means that painful feelings we have—feeling angry with a friend, feeling heartbroken over a breakup, feeling devastated for not getting a part in the school play, or any of the other million painful things that happen as we grow up—those feelings will fade and change, too. Pain today will not be the same pain tomorrow.

It can be hard, though, to remember this perspective when you’re in the middle of something painful, sad, or otherwise hard. Because when you’re in the thick of it, it feels like the bad feelings will last forever. When you’ve just been dumped, it’s impossible to imagine ever feeling better. Pain is part of life and it can’t be avoided—but that’s okay, because just like in running, rough patches don’t last forever. If we hang in there and keep moving forward, we will feel better.

I learned this for myself when I began running more seriously. To run a race, and especially to qualify for the Olympics, it is important to become a master of pain. At the Olympics, I ran the 10,000 meters—twenty-five laps, the longest race on the track. It’s a grueling combination of endurance running and speed. It’s a test of pain tolerance and mental toughness as much as of athletic ability. How much are you willing to suffer?

Throughout my career as an athlete, I’ve come to trust that I can exert myself to my absolute physical limit, and I will (most likely) not die. Deep down, I know the difference between athletic pain, which is good pain, and other kinds of pain, bad pain. Whatever pain I feel while I’m wearing running shoes can never be as bad as the things I had seen my mom do. Bad pain is scary; good pain just hurts.

But just because I have a high tolerance for pain doesn’t mean I enjoy it. In middle and high school, I dreaded every single race. Not because I was anxious about racing well, but because I was terrified of the pain that came with it. I had a very specific daydream that I would entertain before every race: an alien spaceship would land in the middle of the track right before the starting gun and I would get to go home. Nobody could ever make us run after such a dramatic extraterrestrial disruption. But no matter how much I fantasized, the Martians never came and the starting gun always fired—followed by the inevitable onset of pain. The salt-sweat chafing in my armpits and thighs, the swarming ant farm in my legs and stomach, the stinging in my eyes as sweat mixed with sunscreen.

Even when I won, my joy at finishing a race was tainted by the trauma of the pain I had just experienced. I would stomp directly from the finish line over to my dad, who I remember as having a camera for a nose, and report to him that seriously, this race could have killed me, and I simply could not go through this again. My dad would say the same thing every time: “It’s okay, Lex.”

***

When I went to college and started training to compete at the Division 1 level, intense pain became part of my daily routine. Every morning I woke up dreading the inevitable pain to come, and by the time practice started, I felt mentally drained. It became clear that if I wanted to survive as a college runner, I needed to develop a technique to manage my fears about pain. I could no longer afford to spend the days leading up to workouts and races steeped in anxiety. Negative thinking drains energy, and I needed all the energy I had to keep up with my new teammates. Pain and I had to come to a new understanding.

I thought back to middle school when I got into a fight with this girl I really didn’t get along with. When our teacher finally intervened, she quarantined us in a room called “the pod” for an hour to figure things out, just us two eleven-year-olds. My adversary and I spent a good forty-five minutes in silence, glaring at each other from under our unibrows. But in the end we agreed that while we didn’t want or need to be friends, we could be civil for both our sakes. I resolved to be similarly civil with pain. Before my races and big workouts, I worked on consciously shifting my mental energy from dreading upcoming pain to simply recognizing that the pain would always show up no matter what, and even though I utterly despised it, I should try to greet it politely like a guest at a dinner party and be fully prepared to open

the door when it knocks. Sometimes pain arrives slowly, like butter melting on toast. Or it can be quick, like butter hitting a very hot pan. Whichever variety of pain I’m getting, I know it is coming and I am prepared to handle it gracefully. Pain does not have to equal suffering. Pain is a sensation; suffering is a mindset.

The next step was to teach myself to manage the pain once it arrived. Visualization became my most powerful tool: I learned to anticipate which parts of a race would be the most grueling, either by studying the course beforehand or by talking to people who had run the race before. In the days leading up to the race, while jogging, cutting my nails, or scrambling eggs, I’d visualize an Alexi-inside-my-head approaching a specific painful moment along the course and pushing through the rough patch with composure, strength, and even beauty. When I actually faced the challenge in the race, I knew the pain was coming—and, most crucially, I had already made the decision to persevere.

I also discovered using physical triggers, playable actions, as a tool to help my mind overcome the anxiety associated with the onset of pain. For example: “When the pain hits after the third mile, remember to shake your arms out and drop your shoulders.” Or even something as simple as: “When it hurts, force yourself to smile.” By converting a mental struggle into an actionable objective, internal battles felt less elusive and more grounded. It’s much easier to tell myself to move my arms than it is to tell myself to “feel better.”

After I finished school, I started running professionally with my eye on competing in the Olympics. Thrust into this new world of elite runners, I had a surprising realization: my competitors were all experiencing pain, too. I idolized pro runners when I was growing up, and I assumed that these mythical creatures must have figured something out about pain that I hadn’t. There’s no way that these professionals hurt as much as I did. But now that I was up close to this new tier of athlete, I saw that I wasn’t the only one struggling. As it turns out, running hurts for everyone.

Everyone has their own method for managing pain. Some runners wear their pain openly while others hide it very well. But in the same way that it’s usually unhelpful to compare my life to how other people’s lives look on their Instagram feeds, I had to stop comparing myself to how other people in my races looked. Looks can be deceiving, and more often than not, we try to show only the most glamorous parts of ourselves. But it’s important to remember that exterior glamour is never the full picture. Imagine it like this: every person is a planet. Our planet’s core is who we truly are, but the world only sees our outer surface. Ideally, how the world sees us and how we feel and see ourselves are one and the same, but the most important thing is that we acknowledge our core, deep inside our planet-selves—that’s where our true feelings and self exist. And understand that everyone else has a core inside them, too.

I remember in one of my first competitions after college, I found myself running side by side with an accomplished Olympian who maintained a calm face and strong posture despite our grueling pace. I felt intimidated—was this woman not in pain? But then halfway through the race, she suddenly fell behind the pace and completely dropped back, seemingly out of the blue. I’d been so sure that her steady breathing meant that I was alone in my suffering, when in truth she must have been feeling even more pain than I was. Without a doubt, I learned that day that pain is the one thing my competitors and I definitely have in common.

My deeper understanding of physical pain has helped me cope with emotional pain, too. First of all, I know that pain shows up differently for each person and I can never tell just how much somebody else might be hurting. I also understand that whenever I feel bad, I’m probably not alone. And I also know that however badly I’m hurting in this current moment, it will not last forever.

I remember being heartbroken when my high school boyfriend and I broke up after I graduated and moved across the country to college. There’s something uniquely tender about high school heartbreak that makes it especially painful—it’s relentless and all-consuming, like when a baby is crying and crying and doesn’t stop for hours. Its entire world is tears. That’s what high school heartbreak feels like. I felt so sad and lonely that I thought maybe I had made a mistake by going to Dartmouth, a college in New Hampshire, instead of California, and I even started filling out paperwork to transfer to another school closer to home. Luckily my dad encouraged me to stay just a little while longer and finish my freshman year—and sure enough, as the months passed, I started feeling better and came to love Dartmouth.

I know that when your heart is broken or you’re running a tough workout or going through any really hard thing, pain feels like a permanent state. It is real. But it’s also helpful and important to remind yourself that time can and will change your reality. And when it comes to making decisions like switching schools or dropping out of a race early or any other decisions in life we make to avoid pain, it’s helpful to remember that how you feel at first isn’t necessarily how you’ll feel forever.

All pain, whether it’s the physical kind you feel during a race or the emotional kind you feel in your heart, gets better with time. Just remember: all marshmallows, when squeezed, can reinflate eventually.

Bravey Notes

• When you are about to embark on something that might be painful, mentally or physically, you can anticipate the pain and visualize yourself persevering. This allows you to be better equipped when the pain arrives. In this way, you are befriending pain.

• Pain today will not be the same tomorrow. Whether it’s the physical pain of a tough race or pain that’s more emotional, no bad feeling lasts forever. Pain is part of life and it cannot be avoided—but know that if you hang in there and keep moving forward, things will change.