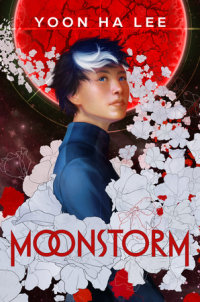

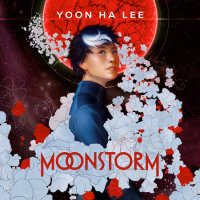

Moonstorm

Author Yoon Ha Lee

Moonstorm

Moonstorm is a part of the Moonstorm collection.

FINALIST FOR THE NEBULA AND LODESTAR AWARDS • LOCUS AWARD WINNING AUTHOR • "MASTERFULLY CRAFTED."—Axie Oh, New York Times bestselling author of The Girl Who Fell Beneath the Sea

* "THRILLING." —Booklist, starred review

EVEN GRAVITY COMES AT A PRICE.

In a society where conformity is valued above all else, a teen girl training to become an Imperial pilot is forced to return to her rebel roots to save her world in this adrenaline-fueled sci-fi…

FINALIST FOR THE NEBULA AND LODESTAR AWARDS • LOCUS AWARD WINNING AUTHOR • "MASTERFULLY CRAFTED."—Axie Oh, New York Times bestselling author of The Girl Who Fell Beneath the Sea

* "THRILLING." —Booklist, starred review

EVEN GRAVITY COMES AT A PRICE.

In a society where conformity is valued above all else, a teen girl training to become an Imperial pilot is forced to return to her rebel roots to save her world in this adrenaline-fueled sci-fi adventure—perfect for fans of Iron Widow and Skyward!

Hwa Young was just ten years old when Imperial forces destroyed her rebel moon home. Now, six years later, she is a citizen of the very empire that made her an orphan.

Desperate to shake off her past, Hwa Young dreams of becoming a lancer pilot, one of an elite group of warriors who fly into battle using the empire’s most advanced tech—giant martial robots. When an attack on their boarding school leaves Hwa Young and her classmates stranded on an Imperial space fleet in dire need of pilot candidates, she is quick to volunteer.

But training is nothing like she expected, and secrets—like the ominous fate of the fleet’s previous lancer squad—are stacking up. And when Hwa Young uncovers a conspiracy that puts their entire world at risk, she’s forced to make a choice between her rebel roots and an empire she’s no longer sure she can trust.

An Excerpt fromMoonstorm

1

Hwa Young, then called Hwajin, was ten years old when her world, quite literally, fell apart.

It wasn’t a world, technically, but a clanner moon called Carnelian for the red hue of its soil. Like all the moons and moonlets in the Moonstorm, it had an erratic orbit. Unfortunately, this month its path had taken it close to the border of the Empire of New Joseon, which left the adults of Hwajin’s household arguing over whether they needed to evacuate and shelter from Imperial attackers.

Mother Aera glowered at Eldest Paik, who stood blocking the door. “You’re wasting time,” she said. “The sooner we get out of here, the safer we’ll be. I was just on the comms with the lookout tower. The Imperials are sending a real fleet for once, not a detachment of raiders.”

“It’s just another false alarm,” Eldest Paik said. Zie had unusual light eyes, almost amber, which shone against zir tawny skin and black hair, shared by most clanners. The oldest of the household’s five adults, Paik was adamantly against taking shelter. Zie…

1

Hwa Young, then called Hwajin, was ten years old when her world, quite literally, fell apart.

It wasn’t a world, technically, but a clanner moon called Carnelian for the red hue of its soil. Like all the moons and moonlets in the Moonstorm, it had an erratic orbit. Unfortunately, this month its path had taken it close to the border of the Empire of New Joseon, which left the adults of Hwajin’s household arguing over whether they needed to evacuate and shelter from Imperial attackers.

Mother Aera glowered at Eldest Paik, who stood blocking the door. “You’re wasting time,” she said. “The sooner we get out of here, the safer we’ll be. I was just on the comms with the lookout tower. The Imperials are sending a real fleet for once, not a detachment of raiders.”

“It’s just another false alarm,” Eldest Paik said. Zie had unusual light eyes, almost amber, which shone against zir tawny skin and black hair, shared by most clanners. The oldest of the household’s five adults, Paik was adamantly against taking shelter. Zie sounded so reasonable that Hwajin almost believed zir, even if the other four adults and older children looked skeptical. “There hasn’t been a full-scale assault since I was a little. The Imperials will harass us for a bit, then go away, like they always do when a moon swings too close to their territory.”

Hwajin watched in silence, fidgeting with a toy she had outgrown half a year ago, a long stick carved to resemble a blaster rifle. She had begun practicing with the real thing when she turned ten. Unlike a kinetic rifle, which fired bullets instead of energy bursts, there was no recoil to worry about. All the clanners, including Carnelian’s settlers, understood the importance of training young, training early, not only to hunt moon-rabbits for the stewpot but to defend themselves from bandits—or Imperial marauders.

The clanners and their intricate networks of families had settled the Moonstorm in centuries long past. Most of them were descended from explorers and adventurers, miners and scientists, who had preferred their freewheeling communities to the Empire’s stricter, centralized rule. At first the Empire had left them alone. But that had changed before Hwajin was born, and so she had always known the Empire as a threat.

According to her family, the Imperials worshiped their Empress and carried out strange, twisted rituals—too strange and twisted to be described in detail to a ten-year-old, which of course made them much more interesting. The Imperials’ rituals summoned gravity, just like theirs did, but their gravity and the clanners’ couldn’t coexist, like oil refusing to mix with water. The Imperials had been fighting for generations to replace the clanners’ rituals with their own, so they could take control of the entire Moonstorm.

Ordinarily, in a situation like this, Hwajin would have just accepted Eldest Paik’s lead. But Hwajin was Mother Aera’s heart-daughter—what the Imperials called a clone, as if the relationship could be reduced to mere genetics. When Hwajin grew up she would have the same angular face, the same long-lashed dark eyes, the same rangy hunter’s build and reflexes. Hwajin couldn’t help but feel closest to Mother Aera, and she hated disagreeing with her. The three other adults—bearlike Manshik, graceful Minu, Yura who cooked so well—were nice enough to her and her siblings and cousins. But Hwajin herself was Mother Aera’s only heart-child, and she was quietly proud of the fact, even at a time like this.

Still, she wished the household’s adults would come to a formal decision one way or another, signaling their vote on a course of action by displaying their knives: blade outward for yes, hilt outward for no.

“At least wait for the sirens,” Eldest Paik added, a small concession.

“By the time we hear the sirens it’ll be too late,” Mother Aera shot back.

A headache pounded against Hwajin’s temples, although she didn’t dare interrupt to ask for willow tea. Ever since she was small, the adults had drilled into her the importance of united action. The clanners had a motto: Do as others do. Stay where others are. Unity is survival.

A queasy sensation began to spread through her stomach. When she looked down at her feet, automatically seeking the reassurance that down was where it ought to be, the queasiness grew worse.

For a moment, as Eldest Paik and Mother Aera continued to argue, Hwajin felt like she was so light that she would float away and fly into the air. Out of habit, she put the toy rifle in her lap and grabbed the edges of her chair. That didn’t help. The chair wobbled slightly as one of its legs, unbidden, rose a centimeter into the air. She bit back a yelp.

At first Hwajin thought the household’s failure to unite had triggered a failure in local gravity. Surely one argument couldn’t affect it this badly? Maybe the neighboring households were also arguing. That might cause it.

“Eldest,” said Uncle Manshik, “we have to come to a consensus.” He pointed at Hwajin’s chair. “We’re losing our gravity.”

It wasn’t the only object that was floating. Hwajin’s toy rifle hovered in the air for a few seconds before touching down again. A cushion shifted; a table rose off the floor and rotated by a few degrees.

Hwajin slid off the chair and landed on the floor—which wasn’t something she could take for granted anymore.

The settlement’s horn went off, long loud blasts. As a small child, Hwajin had thought it sounded like a hunting horn. She’d enjoyed scampering amid the grasses and pretending she was a hunter, driving off the moon-beasts in search of her own prey. By the time one of her older siblings, Sejin, explained what the siren meant, Imperial raiders had wiped out an outpost on one of Carnelian’s sister moons.

Hwajin loved her home. She loved the hilly region of Carnelian where they lived. She loved the starblooms that blanketed the hills’ slopes, glimmering softly in the dark of night. She loved braiding garlands of the flowers to drape over their pillows so they could breathe the tickling-sweet fragrance as they slept.

She didn’t want to leave the walls of rust-colored stone, the windows of rutilated quartz. She didn’t want to wait in the boring shelter. While it had been three years since they had last been forced to take shelter, she remembered the stifling air, how uncomfortably she’d huddled with her siblings while playing card games. Sejin cheated, anyway, and bossy Najin sided with him when she complained.

In particular, she didn’t want to come back to find the walls defaced, the doors smashed open, the starbloom garlands torn apart in a search for some treasure she didn’t own.

“Time to decide,” Mother Aera said. She produced her knife like a stab, blade out. “We’re leaving.”

One by one the other adults displayed their blades, everyone except Eldest Paik.

Hwajin was ashamed of Eldest Paik. Zie was outnumbered. The least zie could do was show zir knife, even if it had to be hilt first, and complete the ritual.

Without waiting for the stubborn Eldest, Mother Aera hefted the bag she’d prepared, which rested against the wall of the common room. One by one everyone picked up their bag. Everyone but Paik and the littlest one, the two-year-old who was too young for a name. Hwajin winced as the straps dug into her shoulders, but she was selfishly glad Mother Aera had prevailed.

The sense of vertigo that had plagued Hwajin ebbed away. Maybe the ritual was good enough to fix things, despite Eldest Paik’s stubbornness. Maybe she didn’t have to worry about the gravity after all. They would be safe in the shelter, and after a bunch of boring card games they would come back home and everything would be all right.

Eldest Paik stood to the side, scowling. Hwajin had never noticed before how stooped zir shoulders were, how rheumy zir eyes, the strands of gray in zir black hair. She’d always thought of zir as being tall and unbowed, the bravest one. Surely zie would acknowledge the household’s will, come along, and lend them zir wisdom.

Hwajin never found out whether Eldest Paik would have abandoned the family. Years later, she’d dream of Eldest Paik’s furrowed brow, zir outstretched hand as zie reached toward them—

To stop them? To join them?

She would always wonder.

The attack came all at once, while Aunt Yura stood in the doorway, struggling to get her bag clear. Except Aunt Yura wasn’t there anymore. The last impression of her that Hwajin received was her long hair curling outward in all directions.

The downward hand of gravity had vanished.

Hwajin heard shrieks. One of them was her own. For several moments, she saw the world as through a kaleidoscope. Fissures opened in the house’s floor, walls, windows. A lamp with an expensive paper shade exploded into a fine mist of light and sparks.

From the time she could understand words, before she could speak, Hwajin had been drilled in what to do in case of gravity failure. But the drills only accounted for minor failures. What use was it to grasp for hand- and footholds if the walls had shuddered apart? When her whole family had been pulled away from her?

She reached out for the flailing hands of her brother, Sejin, who had been standing behind her as they grabbed their bags. At a time like this it didn’t matter if he was the one who made fun of the way she braided her long hair—she needed her brother, needed the solid comfort of his grasp. But as she tried to clutch him, a chunk of wall crashed into her. It knocked her in a direction she didn’t recognize as up, down, or sideways, anything but away. She stifled a scream as a bigger chunk smashed into Sejin. She didn’t recognize him in the spray of blood and grotesque jigsaw of flesh and bone that was left.

“Sejin?” Hwajin whispered, eyes stinging from the particulates swirling chaotically around her, dust knocked loose when the house crumbled into dangerous hunks of rock. The nook by the window that she’d loved so much, the embroidered cushions, the scribbles she and Sejin had made on the wall to “decorate” it for Mother Aera’s birthday—all gone.

Tears floated free, forming gleaming spheres in the reduced gravity. They mingled with the globules of her brother’s blood. Bile choked her for a moment. She couldn’t reconcile the butcher’s meat and its stink with her brother.

Hwajin looked around wildly for Mother Aera. Surely she would know what to do? The suddenness of Hwajin’s motion caused her to tumble in the near free fall, and her stomach lurched.

Just then, a knife floated by, its handle carved with the character for heart.

Mother Aera’s knife.