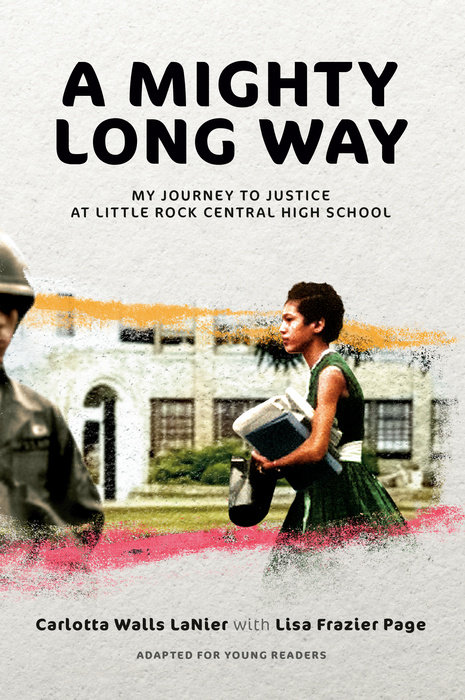

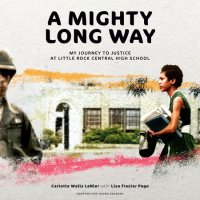

A Mighty Long Way (Adapted for Young Readers)

Author Carlotta Walls LaNier Lisa Frazier Page

A Mighty Long Way (Adapted for Young Readers)

Follow the story of Carlotta Walls LaNier, who in 1957 at the age of fourteen was one of nine black students who integrated the all-white Little Rock Central High School and became known as the Little Rock Nine.

At fourteen years old, Carlotta Walls was the youngest member of the Little Rock Nine. The journey to integration in a place deeply against it would not be not easy. Yet Carlotta, her family, and the other eight…

Follow the story of Carlotta Walls LaNier, who in 1957 at the age of fourteen was one of nine black students who integrated the all-white Little Rock Central High School and became known as the Little Rock Nine.

At fourteen years old, Carlotta Walls was the youngest member of the Little Rock Nine. The journey to integration in a place deeply against it would not be not easy. Yet Carlotta, her family, and the other eight students and their families answered the call to be part of the desegregation order issued by the US Supreme Court in its 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case.

As angry mobs protested, the students were escorted into Little Rock Central High School by escorts from the 101st Airborne Division, which had been called in by then-president Dwight D. Eisenhower to ensure their safety. The effort needed to get through that first year in high school was monumental, but Carlotta held strong. Ultimately, she became the first Black female ever to walk across the Central High stage and receive a diploma.

The Little Rock Nine experienced traumatic and life-changing events not only as a group but also as individuals, each with a distinct personality and a different story. This is Carlotta's courageous story.

An Excerpt fromA Mighty Long Way (Adapted for Young Readers)

Chapter 1

A Different World

For the longest time, I wanted nothing more to do with Little Rock. After leaving in 1960, I returned only when necessary. But my work as president of the Little Rock Nine Foundation would bring me home often. Inevitably, I would wind down Interstate 630 to my old neighborhood. Most often, I would go there to see Uncle Teet, who lived in my great-great-grandfather Hiram Holloway’s old house, five houses down from the one where I grew up. But every now and then, I would pull up alongside the redbrick bungalow at Fifteenth and Valentine Streets, park the car, and get out.

This was the center of my world as a child. The place looks abandoned with its boarded-up windows and weeds, where lush green grass used to grow. There is no sign of the big gardenia bush that once stood in the front yard. Mother would pick a fresh flower from that bush and place it in her hair just so, like the singer Billie Holiday. But the gardenias…

Chapter 1

A Different World

For the longest time, I wanted nothing more to do with Little Rock. After leaving in 1960, I returned only when necessary. But my work as president of the Little Rock Nine Foundation would bring me home often. Inevitably, I would wind down Interstate 630 to my old neighborhood. Most often, I would go there to see Uncle Teet, who lived in my great-great-grandfather Hiram Holloway’s old house, five houses down from the one where I grew up. But every now and then, I would pull up alongside the redbrick bungalow at Fifteenth and Valentine Streets, park the car, and get out.

This was the center of my world as a child. The place looks abandoned with its boarded-up windows and weeds, where lush green grass used to grow. There is no sign of the big gardenia bush that once stood in the front yard. Mother would pick a fresh flower from that bush and place it in her hair just so, like the singer Billie Holiday. But the gardenias are long gone. So, too, is the tree in the backyard that used to grow the plumpest, sweetest figs around. The pecan tree still stands, and as I picked up a few dried nuts one scorching summer day, I was reminded of the Christmas in junior high school when that tree provided perfect homemade gifts for most of my family and friends. Money was tight that year, so I made date nut cakes from the bounty in our backyard to give away as presents.

I’m amazed at how small it all seems now--our house, the yard, and even those pecan trees, which to a little girl staring up seemed just a few steps from heaven. I still call the place “our house,” as if it remains in my family. But Mother finally sold it many years ago when the upkeep became too much and I convinced her that none of her three girls would ever return. She was reluctant at first to let go. The memories, I guess. And our family roots--they run pretty deep through there.

I was three years old when Daddy bought the house at 1500 South Valentine Street, just blocks away from the all-white Central High School. Even then, the school was known throughout the country for its Greek-inspired architecture, beauty, and high academic achievement. Daddy had just returned from the Philippines, where he served in World War II until December 1945. My parents paid $3,000 for the house, sold to them by my mother’s grandfather, Aaron Holloway, who had raised her practically all her life.

Papa Holloway, as I knew my great-grandfather, had tan skin, dark eyes, thick, wavy black hair, and a mustache. I’m told that in his younger days, his hair would sprout into a nest of thick black curls. Our neighbors called him Curly. He stood about six feet tall, and family members say that I--tall and skinny as a child--inherited his height and build. I probably inherited some of his other characteristics, too, like my hair, which, when I was a child, was so long and thick that I had trouble grooming it. Mother had to plait it into neat braids or pull it into ponytails until I was well into junior high school. I wasn’t allowed to get my first haircut until eighth grade, and I’ve mostly kept it short ever since.

The Spanish roots in my family tree can be traced back to Papa Holloway’s father, Hiram. I never knew him, but in recent years I’ve read interviews he did in the 1930s for a collection of ex-slave narratives. Hiram was described in the report as a “tri-racial free person of color,” born in 1848, about thirteen years before the Civil War. He said in a transcript of the interview that his mother was a “full-blooded Cherokee” and his father a “dark Spaniard.” He used the N-word liberally as he talked about the Africans who were enslaved. That word still stings when I see or hear it, but I’ve tried to refrain from harsh judgment of my great-great-grandfather, even as he set himself apart from the enslaved Africans. As difficult as some parts of his story were to digest, the interview reminded me just how much my ancestors endured in their pursuit of education, generations before I ever stepped foot into Central.

“In slave times, they didn’t have any schools for niggers,” said Hiram, who nevertheless managed to learn to read and write. “Niggers better not be caught with a book. If he were caught with a book, they beat him to death nearly . . . They didn’t allow no free niggers to go to school either in slave times.”

Hiram’s story gave me fresh insight into how much my family valued education even then. I wanted to know more about them. Once, I asked Papa Holloway about his brothers and sisters. He told me he had several siblings but that he was in touch with only one, a sister, Maude, who lived in Cleveland. He said that he suspected his other brothers and sisters were scattered throughout the country and passed as white. But Papa Holloway identified himself as “colored” and was proud of the status he achieved as one of the first “colored” building contractors in Arkansas. He helped to build houses throughout the state, and even built White Memorial Methodist Church, where my family worshipped. Most Sundays, I sat proudly beside Papa on the front pew.

Papa’s wife, Mary, died in 1922 at age thirty-four while giving birth to their sixteenth child. The baby girl died, too, as did a set of twins who had been born earlier. Papa raised the remaining children and never married again. His oldest son, Hugh, would become one of only two black men who worked as skilled laborers on Central High School when it was built. Papa’s longtime girlfriend, Dora Holmes, was a widow who lived down the street and owned the house at 1500 South Valentine Street. When Mrs. Holmes died, she left her estate in the care of Papa Holloway, who offered the house to my father.

None of us could have imagined then how much that house would dictate the course of our lives in the years ahead. The house was just west of downtown Little Rock, not too far from Ninth Street, a bustling strip of black-owned businesses and nightspots. The community surrounding Ninth Street was all black. My end of town was more racially mixed--black families lived on one block, whites on the other. In some cases, black and white families lived across the street from one another. But our white neighbors may as well have been living on Mars for all we knew of their lives. Most of the houses in the neighborhood were box-shaped with wooden frames, modest but well kept. A few had porches, and most had small yards, though they didn’t seem small then. Our house stood out because Daddy, who earned a living as a brick mason, meticulously covered it from top to bottom with the same red bricks that remain on the house today. The only other brick house in the neighborhood belonged to Papa Holloway.

Daddy had learned the brick masonry trade from his father-in-law, Med Cullins, a master contractor who did brick masonry work on Central High in the 1940s. Grandpa Cullins, my mother’s father, was a real character. He was a big, imposing man who stood over six feet tall with a heavyset frame, a gravelly voice, and a gruff disposition that matched his size. His beige skin and straight hair gave him the appearance of a slightly tanned white man. He walked with his shoulders squared and head high. Grandpa was his own man. He had one suit and wore mismatched socks, but he considered those kinds of things trivial. Confidence seemed to radiate from him.

Grandpa was not a patient man. He called every man “son” and every woman “daughter,” including his own children and grandchildren, who say he did so because he didn’t want to bother remembering any names.

“Daughter, let me speak to daughter,” he commanded one day when I answered the phone at home.

I looked at Mother and my aunt, who was visiting us that day, and responded: “Which one?”

“Goddammit,” Grandpa barked. “The one who lives there!”

Grandpa Cullins was an intellectual man who had insisted that his four children--Mother, her younger brother, and two older sisters--go to college. Grandpa loved politics, particularly presidential history. Many times, I heard him start with Truman and work his way back, reciting the years each president served, the president’s party, and something significant about each man’s time in office.

All my grandfathers outlived their wives. While I was nurtured by a cadre of well-educated and loving women, I spent a lot of time around the men on both sides of my family. And they heavily influenced the woman I became. The independent streak that I’m sure I inherited from my grandfathers would land me at Central soon enough, and the determination I witnessed in them would help me survive the toughest days at school and onward.

No one was more determined than my Big Daddy. He was Porter Walls, my father’s father. He had mahogany skin and a medium build and was on the shorter side. He had only a third-grade education, but he could read and write and was one of the smartest businessmen I’ve ever known. He owned and operated a pool hall and restaurant a short walk from my house. Big Daddy enjoyed looking like a businessman, so his preferred attire was a suit and hat when he wasn’t in the kitchen. He also smoked cigars.

Daddy had helped his father build the business and worked there part-time. Big Daddy worked at Arkansas Tent and Awnings during the day, while his sisters ran the café. But he split his nights and weekends between the café and pool hall and poured all his energy and every extra dime into building his business.

It wasn’t until I was grown that I truly understood the source of his drive and persistence. It was 1977, and Roots, the television miniseries based on Alex Haley’s novel, had a grip on America. People everywhere sat glued to their televisions night after night, and many black men and women for the first time began digging into their own family trees. I was deeply moved by the drama, which chronicled the life of a young West African man captured from his native land and sold into slavery in the southern United States. All of a sudden, I also was filled with questions about my southern family, and the violent enslavement they had endured.

My questions started with my grandpa, Big Daddy. “Tell me the story of the Walls family,” I said to him one day when I caught him alone.

Big Daddy looked up at me, surprisingly annoyed. “Why do you want to know all that?” he snapped.

Big Daddy was usually a warm, patient man, and he and I were close, having spent much time together throughout my childhood. But he knew what I was getting at, and he was no fan of all the modern talk about slavery and our people needing to discover their African roots. Just a couple of generations removed from the hateful violence and degradation of slavery, he was not eager to remember. The past was the past, Big Daddy figured. No need to dig up long-buried bones. He paused, and finally, peering straight into my eyes, he said:

“Look, all you really need to know is my grandfather owned land.”

The seriousness in Big Daddy’s eyes told me he had nothing more to say. What, if anything, he knew of slavery in his family, he wasn’t willing to share. But he was lucky that somehow in the shadow of the nation’s most brutal system of oppression, his family had managed to accumulate valuable land. That knowledge, that pride, would push him toward his own dreams of owning a business. Eventually, Big Daddy opened a second restaurant and pool hall on the outskirts of Little Rock, retired from his day job, and became his own boss.

Historical records show that Big Daddy’s great-grandfather Richard was born during slavery. It is unclear how Richard’s son Coatney came to own more than 360 wooded acres in Cornerville, the town where the Walls family first settled, about seventy-five miles south of Little Rock. But when Coatney Walls died, the land was divided and passed on in equal shares to his heirs--Big Daddy and each of his seven younger siblings.

In many ways, Big Daddy was ahead of his time. He seemed to have an innate understanding of money and power. All he ever wanted to be was a businessman, a powerful man. He had volunteered for World War I in 1918. When he returned home to Henrietta, the girlfriend he’d left behind, he saw a toddler playing outside. The child was his son. This wasn’t the life he had planned, but he did the proper thing and married Henrietta. The couple eventually moved to Little Rock and had four more boys and two girls. Their third-born was Cartelyou, my father.

Big Daddy worked hard and put aside whatever money he could. At home, he ruled with an iron fist and pushed his children to work hard, too, particularly the older boys. The older two sons could hardly wait until they were grown enough to take the train out of Little Rock and move on to lives of their own making. But Cartelyou stayed, working at his father’s side, soaking in his father’s work ethic and values.

Cartelyou was fifteen when his mother, Henrietta, just thirty-nine years old, died of pneumonia. He grieved mightily and clung to his sisters for support. Soon enough, his younger sister, Margaret, introduced him to one of her friends, a petite, fair-skinned beauty named Juanita. Juanita Cullins was a fellow student at Paul Laurence Dunbar Junior and Senior High School, the premier black high school in Arkansas. It was love at first sight, and on February 3, 1942, the teenagers eloped with another couple to Benton, Arkansas. They were married by a justice of the peace.

Cartelyou was shipped off to World War II on December 7 that year. Eleven days later, I was born. To support us, Mother got a job downtown at M. M. Cohn Department Store, where she worked as a seamstress and clerk, mostly altering customers’ newly purchased clothes. As a black woman, she was not permitted to touch the cash register or receive credit for a sale. Likewise, black customers could shop in the store but were not permitted to try on clothes or return them. Mother, as soft-spoken and dignified as she was good-looking, never complained out loud.

When Daddy returned from the war, she mostly stayed home. She also continued her education at the renowned historically black college Philander Smith, though she stopped short of graduating. Whenever money was tight, she helped out by getting a job, usually as a secretary.