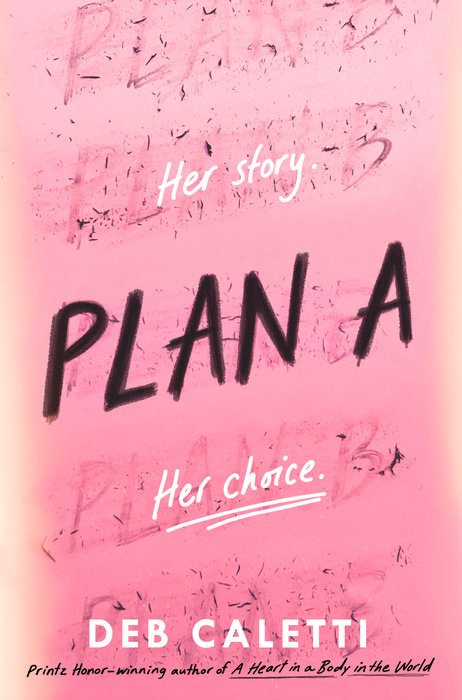

Plan A

Author Deb Caletti

Plan A

A sixteen-year-old girl’s road trip across the country to get an abortion becomes a transformative journey of vulnerability, strength, and above all, choice. From the acclaimed author of A Heart in a Body in the World, this is both an achingly tender love story and a bold, badly needed battle cry about bodily autonomy and the experiences that connect us.

Ivy can’t entirely believe it when the plus sign appears on the test. She didn’t even…

A sixteen-year-old girl’s road trip across the country to get an abortion becomes a transformative journey of vulnerability, strength, and above all, choice. From the acclaimed author of A Heart in a Body in the World, this is both an achingly tender love story and a bold, badly needed battle cry about bodily autonomy and the experiences that connect us.

Ivy can’t entirely believe it when the plus sign appears on the test. She didn’t even know it was possible from . . . what happened. But it is, and now she is, and instead of spending the summer working at the local drugstore and swooning over her boyfriend, Lorenzo, suddenly she’s planning a cross-country road trip to her grandmother’s house on the West Coast, where she can legally obtain an abortion.

Escaping her small Texas town and the judgment of her friends and neighbors, Ivy hits the road with Lorenzo, who, determined to make the best of their “abortion road trip love story,” has transformed the journey into a whirlwind tour of the world: all the way from Paris, Texas, to Rome, Oregon . . . and every rest-stop diner and corny roadside attraction along the way.

And while Ivy can’t run from the incessant pressure of others’ opinions about her body or from her own expectations and insecurities, she discovers a new world of healing and hope. As the women she encounters share their stories, she chips away at the stigma, silence, and shame surrounding reproductive rights while those collective experiences guide her to her own rightful destination.

An Excerpt fromPlan A

1

When I’m not at school, you can find me at Euwing’s Drugs, and so that’s where I am that day, in the staff break room, surrounded by a shipment of pain relievers. It’s not the most pleasant place to be, I admit. There’s a permanent burnt smell in there after my manager, Maureen, once left the Mr. Coffee on all night, and it has twitching fluorescent lights that make you feel like you’re in one of those futuristic movies where someone implanted a microchip in your brain. Still, it’s what we’ve got, so I set my water bottle on a box that reads this end up and try for the hundredth time to start Tess of the D’Urbervilles for Advanced English III. I’m so far behind that it’s becoming one of those things that grow bigger and bigger the longer you don’t do them. I’ve never been this far behind in any of my schoolwork, and we’ve got a final coming up soon, but I just can’t get through the beginning. You wouldn’t believe…

1

When I’m not at school, you can find me at Euwing’s Drugs, and so that’s where I am that day, in the staff break room, surrounded by a shipment of pain relievers. It’s not the most pleasant place to be, I admit. There’s a permanent burnt smell in there after my manager, Maureen, once left the Mr. Coffee on all night, and it has twitching fluorescent lights that make you feel like you’re in one of those futuristic movies where someone implanted a microchip in your brain. Still, it’s what we’ve got, so I set my water bottle on a box that reads this end up and try for the hundredth time to start Tess of the D’Urbervilles for Advanced English III. I’m so far behind that it’s becoming one of those things that grow bigger and bigger the longer you don’t do them. I’ve never been this far behind in any of my schoolwork, and we’ve got a final coming up soon, but I just can’t get through the beginning. You wouldn’t believe how many pages there are before that thing actually starts. There’s a foreword, and then an explanatory note to the first edition, and then a preface to the fifth and later editions. I’m not even kidding. You practically expect an introduction to the 109th edition.

Blah, blah, blah, preface. If you ask me, they ought to be outlawed, the pages before the pages. And if they’re in italics, forget it.

You have a lot of opinions, Ivy, my mom always says.

Which is, of course, an opinion.

She has a lot of them, too—opinions about music and men, guitars and rom-coms—and so does Grandma Lottie, about everything from shit cars to fast food. It’s a thing in my family, especially among the DeVries women, to see yourself as strong-minded and willful, fierce. Also, that old-fashioned word “plucky.” But I can tell you one thing—right then, I don’t feel very fierce, and you’d need way more boxes of pain relief to fix the hurt swirling around in my head. Swirl—my stomach, too. Forget about eating.

To get to the actual beginning of the book, I just skip all of it, all those pages that seem so meaningless. Fine, whatever, get to page seventeen, where the thing actually starts. You know what’s funny? The first line. On an evening in the latter part of May, it reads, and right at that moment, it’s actually an evening in the latter part of May. Something about this makes me think of our dog, Wilson, chasing his tail. Going around and around only to end up at the same place.

Stop being a preface, Ivy, I tell myself. Get on with it.

I sigh long and loud, even if no one hears it, and take off my blue vest with my name tag pinned on. In order to reveal my future, I open the book to a random spot to see what it says. Pages 142 and 143. My life looks as if it had been wasted for want of chances! Wow, thanks. Come on, book, you can do better! I close my eyes, move my finger down the page, and stop. What’s the use of learning that I am one of a long row only?

Oh my God. Or oh somebody’s God. I wish he were mine, but the way people around here talk about God, he too often seems like the worst bad boyfriend—moody, mean, and impossible to please.

Ms. La Costa did say that Tess of the D’Urbervilles was the most depressing book ever as she handed out the copies in class, her legs shush-shushing from her nylons. How can it not be? It’s about a woman in the 1870s who gets raped and has a baby, and then her whole town basically ostracizes her. When Olivia Kneeley said, Why do we have to read it, then? Ms. La Costa said, We still have to look.

I wrap up the second triangle-half of my peanut butter sandwich, tucking it into a plastic-wrap swaddle. It’s one of those awful times when everything seems to be telling you something, even a peanut butter sandwich. Mini fridge, checkered linoleum, the curve of an orange peel in the trash, goodbye. I gather my things. Bending down, I tie my shoes even though they’re already tied, like you do for a marathon.

My opinions—they don’t have the power to wreck lives, though. They don’t have the ability to make you so scared and so ashamed that you’ll do what people want you to do, even if it destroys you.

--

This all could be so easy, since I’m right there at Euwing’s Drugs, where I’ve worked three days a week after school for two years now, and all day in the summer. Those very boxes are right in reach. But it’s not easy. It’s not Tess hard, but it’s hard enough that I haven’t slept for days. A scary dread keeps popping out at unexpected times, same as Diesel, our neighbor Mr. Sykes’s dog, who snarls and flings his body against the chain-link fence whenever anyone or anything passes by.

“Be right back,” I say to Maureen, who pinches her lips together and adjusts her own blue vest with the name tag that reads maureen and, under that, in print so small you practically have to have your face in our boobs to read it, how can i help you? She hates me. She absolutely hates me. I hate her daily tuna, how the smell of it merges with the old burnt coffee, but I try really hard to see the good in her. Whenever I relay all the thrilling drama at Euwing’s Drugs for my best friends, Peyton and Faith, Peyton says for the millionth time, She’s just jealous—you know that.

I know that. I’m the youngest assistant manager Euwing’s has ever had, according to Mr. Euwing. Bob. Call me Bob. No more of this Mr. Euwing business. You’re making me feel old! Promoted to management in only two years. While I’m still in high school. It took Maureen, who’s, like, forty or fifty, something like fifteen years to be assistant manager, and two more to make manager after Flo died. I get it. I’d be jealous, too. I keep trying to be nice to her to make up for it, offering her a mint, giving her compliments about her hair or her latest manicure design, but there’s no going back to the days when she’d pat my shoulder and say, How you doing, Ives? Mr. Euwing tapped the magic wand on my head because I’m his favorite, and who likes a favorite? I’d hate me if I were Maureen, trudging in to work all those years and then hearing Mr. Euwing say stuff to me like, I want to support your goals! I don’t even know what my goals actually are. Go to college. Make money. Definitely see some places beyond Paris, Texas. Definitely see the real Paris someday, the real lots of cities in lots of countries, even. That’s as far as I’ve gotten.

I try to walk casually across the store, past the aisles labeled first aid and beauty and seasonal. I don’t look at that wire cage by the door with those two lovebirds inside, Buddy and Missy, with their orange heads and curved red beaks and those black bead eyes on a circle of white that look like the plastic eyes you can find in a bin at Shelley’s Craft and Quilt. Those eyes are so creepy and lifeless that you better make a joke about them, fast. Euwing Opaline Lovebird, Mr. Euwing will tell you. That’s right! They have my last name! How can I not want to own them? He’ll tell you much more than that, too—how they’re a mutation of two mutations, Euwing and Opaline, how you can pair two birds to actually design the bird you want. You can change its color. You can stop it from flying, even. “Birds don’t belong in cages” is another opinion I have. What a life, to be forced inside, the door shut on all the possibilities that are right out there for you to see but not have. I hate the way those birds lift their feathers and peck at their small fat bodies and screech and scream. They make me so uneasy, I always try to avoid them, unless Mr. Euwing is watching.

Outside, I stroll all casual until I’m sure I’m out of sight of Maureen and Evan, who’s at the register. Then I take off. I run so hard, my backpack bangs against my side until I’m practically falling at the automatic doorstep of Euwing’s archenemy, CVS. Giant corporation, forcing out the little guy. “Everything always seems to be about power” is another opinion I have. I step on the black mat, and the door whooshes open, which seems so upscale compared to our regular old door that you have to actually push. Everyone pulls, even though there’s a sign right on it. Customers who have been coming for years do it, because, let me tell you, the force of habit is strong. If you watch Wilson go outside to pee, you even wonder if habit is inborn. Sniff the same two bushes, lift leg on tree, repeat for years, even when I try really hard to get him to view the yard in a new way.

Inside CVS, air-conditioning hits, and a wall of cool suddenly surrounds me. Goose bumps prickle up my arms as I face the display of Pump-Up Max protein powder on sale that greets you as you walk in. The store is bright and clean and new, and so big that it’s almost hard to see the anything in the everything. I glance around like a spy. My heart beats a guilty gallop, as if I’m about to rob the place. I didn’t imagine how this would actually feel. Well, it feels bad. Really bad. Like a shame python is wrapping itself around me and squeezing.

No cart, just a basket, the kind with the metal handles covered in a thin roll of red plastic. I get a hairbrush, on sale, protected in its transparent dome. A bottle of Suave shampoo, strawberry. A box of Red Vines for a dollar twenty-five. A box of Junior Mints for ninety-nine cents. A cheap mascara. When I get to that aisle, my face flushes. It’s mid-May and warm, eighty-two. Paris doesn’t get hot like the Texas desert where my dad lives. It once got to be one twenty in Odessa. But I’m perspiring even in that air-conditioning. Still, I wish I had a sweatshirt or something to cover my bare arms in my sundress. My skin feels all exposed, because when you’re in that aisle, the one way in the back, it’s the aisle of disgrace, where you stand there and publicly admit that you had sex or are about to have sex or that you get your period or can’t control your bladder.