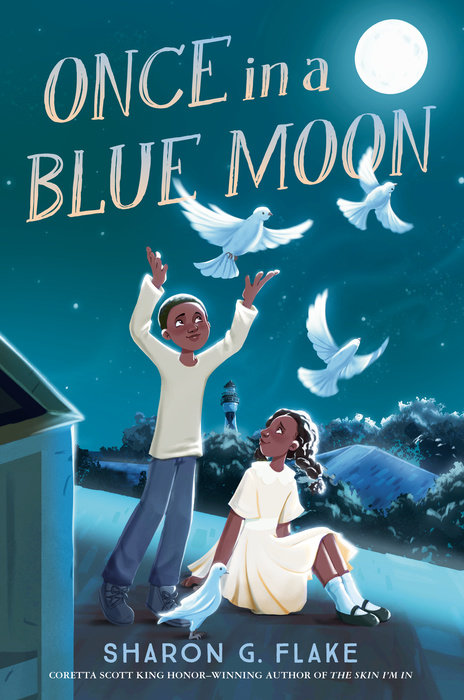

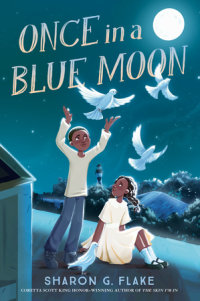

Once in a Blue Moon

A beautiful and uplifting novel in verse about family, friendship, journeys that take us far from home and back again, renewed and more courageous from the three-time Coretta Scott King Honor winner of The Skin I'm In!

James Henry used to be brave. He hasn't been the same since that fateful night at the lighthouse when his ma went searching for Dog. Now months later, he feels as small as the space between the numbers on a watch, nervous day and night, barely able to go outside. Even words have a hard time leaving his mouth. The only person he speaks to is Hattie, his courageous twin sister, who fiercely protects him, especially from bullies.

James Henry wants nothing more than to be brave again. However, finding his voice will mean confronting the truth about what happened at the lighthouse-a step James Henry isn't sure he can take. Until a blue moon is forecast, and as Gran has said, everything is possible under a rare blue moon . . .

* "An evocative, immediate novel with compelling characters and a wonderfully well-paced plot." —The Horn Book, starred review

An Excerpt fromOnce in a Blue Moon

Me

People ask about the boy

behind the door

inside the house

me.

Mostly Sister gets the questions.

She chases away boys

girls too sometimes

who wander onto our property

to gawk and stare at me

the one

folks hardly see

but everybody knows about.

Me and Sister

Hattie and me are twins

not that we match exactly.

She’s two inches taller

I’m two minutes older

a boy.

Eleven

though I seem younger.

Maybe that’s why Hattie likes to boss me around.

But I’m the captain

today anyhow.

Which means

she’s got to follow my rules.

My Condition

Sometimes

I feel as small as a flea

as little as the space between

the numbers on a watch.

It makes living hard

staying inside easier than leaving the house.

Right now

I’m on my knees

on the couch

by the window

staring out—like usual.

Hattie’s

to the right of the porch

next to the gravel walkway

in front of the bushes Gran asked her to trim

yesterday.

It’s a boy’s job

my job

but given my condition

Hattie gets to take my place

more than I’d like

not that I like

toting pails

feeding chickens

milking.

The Way Things Are

We live in Seed County, North Carolina.

Daddy is in Detroit

working.

Here, it’s me

Gran

and Hattie in the house.

Uncle comes by now and again.

He don’t like me much.

Hattie’s Way

How many times you got to call

a girl before she answers?

One time?

Two times?

Ten?

“Hattie Mae!” I say again.

Outside past the porch

she squats low

picks up a rope

that came from Detroit

wrapped around a box of new dresses

sent to her by Daddy.

She holds both ends

swings

that rope

over her head

jumps

HIGH

sends dirt flying.

Still

she ignores me.

Could be she’s mad at me.

This is the third time this week I said

I’d go outside

try to anyhow.

Only I can’t.

Sister’s Song

Sister is dressed for Sunday

when it’s only Wednesday.

She sings while she jumps

hops

skips.

“Miss Mary Mack, Mack, Mack . . .”

But as soon as her song starts

it stops.

“Everybody’s got a condition,” she says.

“Pastor wheezes when he preaches.

Sneezes come spring.

Still

he gets out the house.”

I get out

at night, at least.

If folks looked up, there I’d be

on the roof

under the sky

talking to Hattie

the only one allowed up there

besides me.

My rules

even when I’m not the captain.

Lighthouses and Blue Moons

Sister takes her sweet time walking

up the pine front-porch steps

sawed and nailed in place by Granddad, who built the house.

Halfway between the porch and me

she stops

gives Gran a hug

reminds her that there’ll be

a blue moon in a few months’ time.

Who don’t know that?

The almanac calls

the second full moon in a month

a blue moon.

It don’t happen too often.

Which makes it a big deal

important

unusual.

Gran calls it a wishing moon.

What you want for, wish for

or need

on that day is yours

according to her.

Which is why Hattie is nagging me so.

If I’m to be rid of my condition

she believes

we need to get to the ocean

on the night of the blue moon

get to the lighthouse too

where I was when everything changed.

Which means

I have to get out of this house first.

Only I can’t.

Why don’t folks understand that?

Ma would.

Hattie in the House

Hattie comes inside

when I say I don’t feel so well.

Sister swears it’s nothing.

Just me worrying

or about to.

Still

she puts her hand on my forehead.

Feels like something.

Needles poke my legs.

Fire burns my toes and fingernails.

My insides

hum

like guitar strings just plucked.

It’s my nerves

playing tricks on me

Doc Edwards claimed

during his once-a-month visit.

Feels like something worse.

“Hattie,” Gran says from where she sits rocking

on the porch,

“leave him be.”

Hattie stands behind me.

Hugs me.

Brings up Doc Edwards.

I shiver

get cold to the bone.

My worrying is a worry to my soul

brain

blood and everything that makes

me

me

Doc Edwards said before he left town for good.

“Get him outside in the sun.

Drag him if you must,” he told Daddy

not long after the accident

plus a few more times besides.

Daddy never did. Never would.

He understands me good as Ma.

Ma’s Twin

Uncle said

it was a fool’s errand

that sent me to the ocean that night

with Ma chasing after me.

More About Uncle

Uncle

never did trust up-north

big-city

fast-talking

pointy-toed-shoe-wearing folk

Negro or white

not even Daddy at first.

Till Ma introduced him to Daddy’s cousin Sarah.

She’s our cousin and our aunt now.

They married ten years ago.

Got no kids

just each other plus a big white house.

Uncle came back south when Gran got sick.

Ma followed.

For just a spell they both said.

Then he got a job with the railroad.

Ma started teaching.

Six-two

pecan brown

Uncle dresses in clothes plain as paper bags.

Brown

brown

always brown.

His car is fancy, though.

His house has three floors. He built it himself.

Some nights I stayed with them. He liked me then.

Ma

If it wasn’t for Ma

I would believe what people say about me

that I’m peculiar

odd

a coward.

That night

Ma called me brave

strong

her little man

the smartest boy in Seed County.

I never told anybody that.

Rooftop

On my back

on top the roof

laying on a blanket

with my toes aimed at the sky

I forget my troubles.

The moon lights up the night.

Lights me up inside

fills me up

calms me down.

Hattie too.

Sister is nearby with her birds.

Standing in front of cages

stacked wide and high

Hattie looks after her treasures

doves

that think they’re hawks.

Twelve in all.

Only Nutcracker is free right now.

Above My Head

Nutcracker flaps his wings

heads for his favorite spot

a chicken-wire fence Daddy put around the roof

so we don’t fall off.

Hattie sets another dove free

then another

till

there’s ten of us on the roof

one complaining—

me.

The others coo

peck at seeds

corn kernels

dry peas

that Hattie scatters

in the cages

on the roof

and me.

I close my eyes again

think about Buck Rogers

who is nothing like me.

Full-grown

white

he lives in the twenty-fifth century

five hundred years in the future.

Ray guns.

Starships.

High-frequency impulses.

I never heard of such things

before his radio show.

Uncle doesn’t like it one bit.

Says Buck and me

do the devil’s work

by meditating on places

God never wanted folk to go

Venus

Neptune

Pluto

the Milky Way

the moon.

When I think on them

and other things above

I don’t fear anything.

Night Trains

The train runs along the track

behind our house.

Black

spitting steam

it heads this way

on its way to the station.

Hattie’s birds squawk and swoop.

I

pretend

I’m in first class

on my way to Sirius.

Captain Me

Hattie sits beside me

in a rain barrel I sawed in half.

I check the controls—

buttons and knobs

whittled out of wood

hammered

and

nailed into place with my very own hands.

Sister shifts gears using an old ax handle she swings in the air.

“Ready?” I ask.

Sister salutes.

“Aye, aye, Captain.”

“Head protector?” I ask.

She pats her helmet

Gran’s old church hat covered in tinfoil.

“Check,” she says.

“Rocket fuel?”

Sister lifts a seltzer bottle full of well water.

“Enough for a month, sir.”

“Jet pack?”

“Yes sir.”

We got suspenders strapped on our backs

stitched to feed sacks filled with dried peas

handmade by Gran.

Hattie Mae licks her baby finger.

Holds it high.

“Good news, James Henry. Yesterday’s storm

did not excite the wind too much.

We should make it to Neptune in record time

without being blown off course.”

I bolt the cabin door shut. “Ready?”

“Set,” Hattie says.

“Blast off!” we scream.

The train rolls by.

Houses rumble and shake

including ours.

Smoke from the engine nearly blinds us.

Still

I see coloreds and whites on different planets.

Neptune not that far away.

To Outer Space and Beyond

“Space rocks!” Hattie Mae hollers at the top of her lungs.

Her birds know their parts.

Most times they stay in their cages

but before we got started she set ’em free

eight of ’em anyhow.

Pullman circles the roof—

Squawk!—

dives down

grabs buttons with his claws

drops ’em on us.

Aberdeen

named after Ma

goes for the acorns.

Other birds pick up sticks

just like Sister trained ’em.

Our anti-radiation tinfoil hats

get hit from every which direction.

It doesn’t hurt us any.

It’s our rocket ship that’s damaged.

The engine cuts off.

“Sssssssss,” Sister says.

The cabin light follows.

Birds go back in their cages.

In the dark

without power

we drift off course—like Buck Rogers.

Down

down

down

our spaceship goes

till we’re in a part of the universe

we never saw before.

Sister pulls out a flashlight.

The head is covered with cheesecloth.

Light rays shoot from it like sun through fog.

“It’s . . . so empty out here. Quiet,” I say.

Sister screams, “Aliens!”

I zap their tentacles with cow’s milk.

Point to our instruments spinning out of control.

Hattie grabs her throat. Coughs. “We’re losing oxygen. . . .

I . . . I’m dying . . . James Henry.”

She faints

the way them movie stars do at the picture show

flopping over the side of the rocket ship

eyes crossed.

I stand up. “I . . . won’t . . . fail . . . you . . . Sister!”

“Oh goodness,” I hear Gran say from inside the house.

“The whole dang town can hear ya.”

With all my strength

I give the instruments a good hard kick.

Hattie comes to. “Thank goodness.”

Sits up

claps.

A few hundred million miles later

we’re floating through space in peace.

Captains Ain’t Afraid

I

shut down the engine.

“Have you ever seen anything like it, Hattie?”

“Not in all my born days.”

I unbuckle my belt

decompress the hatch like Buck.

Open the door.

Check my oxygen levels.

Take off my helmet

and breathe.

Space air smells sweeter than earth air.

More like them green-apple pies Gran bakes

and wins prizes for.

“Up here

we can drink from any fountain.

Sit in any seat we want.”

Hattie nods, then follows me out.

“When we meet those space people

don’t be scared, you hear?” she says.

I beat my chest. “I’m the captain.

And captains ain’t afraid of nothing.”

Hattie floats past me

because there’s no gravity in space.

Tiptoeing behind birdcages, we search for stuff

we came with earlier

chicken feet

tree bark

rabbit teeth

eggshells stomped to pieces.

Things we astronauts call by other names

meteorites

space dust

moon rocks.

“Space critters sure are messy,” Sister says.

Kneeling

she picks up pine needles

drops ’em into medicine bottles

calls ’em alien bones.

The sound of Gran’s bell

a cooking pot she hits with a wooden spoon

finds us way up here in outer space.

“Suppertime! Y’all come,” she says.

We keep exploring

filling our helmets with our finds

lose track of time until I hear something.

“Squeak.”

I

freeze.

Seems like my heart stops too.

Hattie Mae swallows. “It’s nothing.”

It’s them and she knows it.

Sister keeps to her space job

collecting marbles

we plan to trade with space pirates

in case we need to bargain for our lives.

“Squeak.”

My fingers find my mouth.

I chew my nails.

Between bites, I ask

if she heard what I heard.

Sister lies. “No.”

“You had to, Hattie. I know it.”

I back up

find the darkest part of the roof

the space between the cages and the fence.

Squatting

I squeeze my eyes tight.

“Squeak.”

“Squeak.”

“James Henry. We know you up there.

You coward.”

The Baker Brothers

“Titus Baker, take this.”

“Ouch!”

Sister pitches coals over the chicken-wire fence like baseballs.

Her aim is always perfect.

Titus Baker finds that out soon enough.

“Hattie Mae,” he shouts up to us.

“Your brother’s got it coming, and you know it!”

I try to keep myself calm.

But my mind ignores me

like always.

Run.

Go in the house.

Hide under the kitchen table.

My forehead gets wet as water.

Drips sweat.

I rub my eyes

but cannot wipe my thoughts clean.

So

I take off running.

Pecans fly over the chicken wire like bullets

hit my chest

sting my neck

chase Hattie’s birds

rattle the rest still in cages.

I go back to where I was.

Hattie follows.

Crouching low beside me

Sister reminds me that there’s a blue moon coming and

when a blue moon shows up

everything

is

set

right

again.

“Everything?”

My hands tremble like collards in a December wind.

“Even me?”

I think of myself the way I used to be.

Brave.

“Even you, James Henry.

Which is why tomorrow you have to start practicing

getting out the house and

used to the world again.”

I want to agree

but my thoughts won’t go along.

They

ruminate

pester

worry me.

What if she’s wrong?

What if I make it to the ocean and drown

once and for all this time?

The Baker Brothers Plus One

“James Henry!”

The Baker brothers live

up the road a piece.

Their father’s cow always breaks free

finds its way to our house.

The brothers—five of them—are mean as ground hornets.

“Want to go swimming?” Titus shouts.

He’s the eldest Baker boy.

“Don’t let me come down there,” says Hattie.

Them Bakers standing with their cousin Red

bring up other things

that scare me

fire

crowds

leaving home

folks touching me

all except Hattie, Gran, or Daddy.

“Sister,

you won’t let ’em get up here, will you?” I ask.

“No, Brother. I won’t.”

“Gran won’t either, will she?”

“Never, James Henry.”

“And if they come

they won’t find me, right?”

“They won’t get past me, James Henry.

I’ll always protect you. You and me twins.”

“But what if there’s lots of ’em sometime?

A whole crowd of ’em.

A town’s worth

of kids trying to get to me.

Then what?”

“They know, James Henry, that I

can whip the whole lot of them, if I must.

We’ve been on the moon, haven’t we?

To Ursa Major and back.

Me and you can do anything.”

“Anything.”

“Yeah, twins are like that.”

I get on my knees.

Breathe in slow and easy.

Remind myself that long as Hattie is with me,

nothing bad can truly happen.

But then I smell it.

SMOKE.

Sister Saves Me, Again

Hattie tells me to stay put

Not to

look.

Not to

think

what she already knows

I’m thinking.

What if the house burns down?

What if Gran can’t get out?

What if we’re trapped up here?

What help would I be?

I couldn’t even save Ma or Dog.

Just stood there.

Not even Hattie knows the whole story.

More smoke floats up to our planet.

I cover my nose and mouth.

Hattie calls for two birds

Wilma

named after Buck Rogers’s assistant

and Pullman

named for the dignified

hardworking

sleeping-car porters

who formed their very own union.

“Get ’em!” she shouts.

Hattie ain’t the captain. I am.

Sometimes she forgets that.

Like now

when she jumps over the chicken-wire fence

leaps to the ground

with her arms wide as dragon wings.

I run to the chicken wire

cheering.

The Bakers and their cousin Red

run too

up the road in every which direction.

Anybody would,

with Hattie and her birds

chasing ’em.