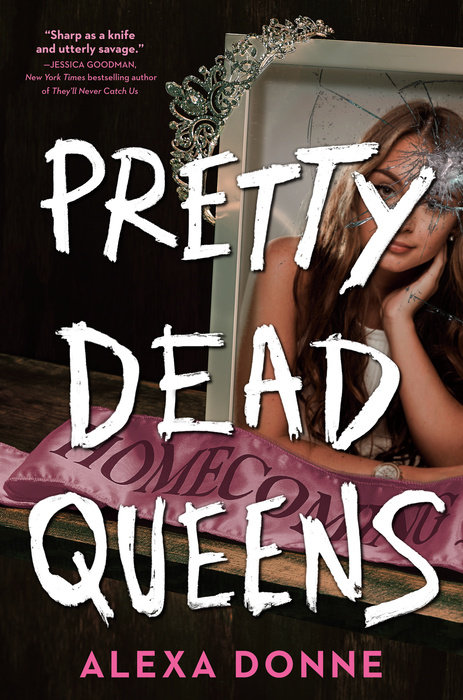

Pretty Dead Queens

The new homecoming queen is dead . . . and she's not the first unsolved murder at Seaview High. From the critically acclaimed author of The Ivies comes a nonstop YA thriller about a decades-old mystery, a copycat killer, and the teen who will stop at nothing to uncover the truth.

"Utterly savage." –Jessica Goodman, New York Times bestselling author of They’ll Never Catch Us

"Hand this fast-paced thriller filled with plenty of twists and drama to fans of Holly Jackson or Karen M. McManus." -SLJ

A 2023 Edgar Award Nominee!

After the death of her mom (screw cancer), seventeen-year-old Cecelia Ellis goes to live with her estranged grandmother, a celebrated author whose Victorian mansion is as creepy as the murder mysteries she writes. On the surface, life is utterly ordinary in the California coastal town . . . until the homecoming queen is murdered. And she’s not Seaview’s first pretty dead queen.

With a copycat killer on the loose, Cecelia throws herself into the investigation, determined to crack the case like the heroines in her grandmother’s books. But the more Cecelia digs into the town’s secrets, the more she worries that her own mystery might not have a storybook ending.

An Excerpt fromPretty Dead Queens

CHAPTER ONE

Some people attract death.

When I was nine, my pet rabbit, Easter, flopped out of my arms while Mom was cleaning her cage, and my bunny’s back snapped in two. The fall didn’t kill Easter, but we had to take her to the vet to put her down. I didn’t cry.

When I was six, Granddad went to the angels. That’s how my grandmother put it. Mom had a more literal take. “He’s dead!” she screamed at her mother. Wailed. It was the first time I ever saw my mom cry.

Then there was our dog, five years ago. My chemistry teacher, who was felled by an aneurysm when I was in ninth grade. The pretty junior girl my sophomore year, DOA in a horrific highway crash.

I am just shy of my eighteenth birthday and on my sixth funeral.

It’s the worst kind of funeral that brings me to Seaview and my grandmother’s creepy-as-hell Victorian mansion off Main Street. (Yeah, this place has a Main Street.) The peeling velvet wallpaper is straight from a Poe story.

“It’s original hardwood!” my grandmother says. “People shit themselves for floors like mine!” She sweeps across said floors, which surely hide long-desiccated corpses, without hesitation. I pause at the threshold, the porch creaking beneath my feet. If I step over, follow this strange yet eerily familiar woman inside, it will be real. I will live here now.

But I don’t exactly have a choice. Everything I own has been packed up, sold off, or put in storage. It’s this or foster care. Maura Weston is the only family I have left. Even if I barely know her, legally she’s my guardian. This is my home.

My mom is dead, and I’m living with a stranger.

I step through the doorway. Look up the grand staircase to the landing, where Mrs. Danvers is surely waiting. But it’s only Maura and me in this cavernous Victorian relic.

“Call me Grandma,” she’d said on the drive from the airport. “My fans call me Maura. You’re not a fan, are you, dear?”

It seemed like a trick question.

“I read the one set on the boat,” I’d said, and it appeared to please her.

“That was a New York Times bestseller,” she said, beaming.

A lot of them are New York Times bestsellers.

“You’ll be on the fourth floor,” she tells me now. “You have your own bathroom, so lots of privacy. Plus, you have those gloriously young knees, for all those stairs. Suzanne’s in the carriage house out back. You’ll meet her in the morning.”

She mentioned in the car that her assistant, Suzanne, was supposed to pick me up but there was a last-minute change in plans. I can’t tell whether Maura is annoyed by the inconvenience. It’s late, eleven o’clock, because Seaview is on the ass end of nowhere. Northern California: where, with layovers, it can take you four hours to fly from one regional airport to another and then you still have to drive two hours to your destination. But her expression remained in a pleasant-grandma mask. A brave face for the orphaned grandchild. Warm hugs and sad smiles.

“You’ll want to get to bed, since you have school in the morning. I’ll take you to get registered. Eight o’clock sharpish. They’re expecting you.”

It’s early October, so school has already started. I’ll be the strange new kid with the dead mom, moving in with the town’s most famous resident, and six weeks of work to catch up on, because death does not time itself conveniently to school schedules. Not to mention the lifetime of friendships I’ll never edge in on. Kids in towns like these are born here, die here. Relationships go from womb to tomb. My mom hated it. People were always coming and going when we lived in LA. Easy to be anonymous.

I lug my suitcase behind me, the tired wheels scuffing against honeyed hardwood until I reach the foot of the grand staircase. I brace myself to heft my bag--my entire life somehow reduced to a single suitcase--all the way up.

“I think that will fit in the dumbwaiter,” Maura says, backlit by the warm hallway light, haloed like an angel. Silver hair, peppered with the barest wisps of deep brown, cut short, ear-length, and flipping out at the edges. Big brown eyes with lids smudged smoky gray. Brows overplucked, the vestiges of a vintage trend. An old woman reflecting the heyday of her youth.

I search for my mother’s face in hers. Try to imagine Mom if she’d been allowed to reach old age. Pointed chin, yes. Maybe the cheekbones. The turn of her mouth. Not the eyes, though. Mom’s were deeper set. She’d have killed to pull off that eye shadow, or a delicate wing, like I can.

“You got that gorgeous wavy hair from me. You’re welcome. But those eyes . . . must be your father’s,” Maura says, apparently taking me in as well. “You’re lucky. Such a pretty color.”

Green, like the phantom man my mother wouldn’t talk about. It was one of the few sore points between us. My father is a ghost. My mother, now ashes. My grandmother, a stranger. But she’s agreed to take me in, and she’s sweet enough. And very rich. This old mansion is nine times the size of the apartment Mom and I rented in Pasadena.

“It’s this way.” She tilts her head toward the kitchen, leads me back. It’s an HGTV fantasy land. Old mixed with new. A showstopping cast-iron stove alongside state-of-the-art appliances, an updated subway-tile backsplash and farmhouse sink, a sprawling kitchen island with barstools lined up like soldiers, and original wood cabinetry. And to the right as we come in, nestled at the very edge of a back stairwell, an unassuming cupboard door. Maura undoes the latch, swings the door wide. An extralarge dumbwaiter.

“We removed the shelves decades ago for this very purpose. Give it a try with your bag,” she says.

It takes the both of us to haul it inside. The bag barely fits, and the bottom of the miniature elevator shudders under the weight. Maura seems nonplussed.

“My mother’s tea service weighed more than this, surely. The bitch of it will be your having to haul it from the third to the fourth floor. I’m not cut out for that anymore. I’m a firm sixty-eight--but not that firm.” She winks. It’s strange hearing the word bitch out of someone so old, but she’s already graced me with a creative array of curses in the car. It seems I have a cool grandma.

“Let’s go,” she says, halfway up the back stairs. The servants’ stairs, they would have been, way back. I wonder when they stopped having live-in servants here, but then I remember Suzanne. Maura explained to me that she used to be her assistant when she lived in New York, and she couldn’t function without her, so when she moved back to Seaview permanently, she set Suzanne up in the guesthouse in the backyard. Maura assured me she pays her a handsome salary to live in the middle of nowhere. I wonder if Suzanne has as rosy a view of the arrangement.

“This is where I leave you,” Maura says on the first landing. I peer around the bend, spying a spacious bedroom at the end of the hall. “It’s good to have you here, Cecelia, even if the circumstances are . . . well.” She sighs. Sniffs. Dabs at her eyes, shiny with tears. “My poor baby girl, Vanessa. Parents shouldn’t outlive their children,” she says, more to herself than to me, I think.

“If only you’d called me,” she continues. “I hate that you were alone at the end. That she didn’t have her mother. And you cremated her? Honey, there’s a family plot right here. Or if the problem was money, you know I have more than enough!”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know how to get in contact with you. I sent an email to your agent, but didn’t hear back until it was too late.” It comes out a jumble as panic slams through me. That I fucked up what I was apparently supposed to do.

Maura’s mouth tightens into a white line. “Yes, well, he won’t be getting his fifteen percent off me anymore, don’t you worry. Anyway, you’re here now. And don’t worry about the burial thing. We’ll scatter her ashes together when you’re ready.”

And now the grief chaser: that my mother’s ashes are sitting in an ugly, overpriced urn at a family friend’s house in LA because I was frozen by the thought of how the hell to get it all the way up here. Maura will kill me. But she’s folding me into a hug before I can get the words out. I’m stiff, awkward, but she is warm. I relax into her, just so. Then it’s over.

“See you in the morning. Holler if you need me, though you’ve got ten minutes before I’m out like a light. So make it quick if you do.”

I continue up, up, huffing slightly as I reach the third floor. I’m going to need to develop better cardio and strength if I’m going to live here. I locate the dumbwaiter to my left. The door creaks open. It looks rarely used, but the inside has recently been retrofitted. The rope is new, and all I have to do is push a button to the right of the door to activate the pulley system. Two minutes later and I’m hauling all my earthly possessions up the final, narrow staircase that leads to the fourth-floor attic space.

The landing is small; I’m in the eaves of the house. There are only two rooms on this floor. A door on either side of me. I try behind me and find a white-tiled private bath: nothing special, yet twice the size of my old one.

That makes the other door my new bedroom. Skylights have been cut into the slanted ceiling, bookshelves installed in the low-slung walls. The windows are open, but it’s still a bit warm. This place must be murder in the summer. There’s a window nook with a bench, framed with pretty purple curtains. A desk, by the look of it brand-new--some unpronounceable Ikea piece--against the left wall, and a double bed with an elaborate wooden headboard abutting the right.

Purple was my favorite color when I was six. I’m touched Maura remembered. Now, though, I love green. Like my backpack, whose straps are digging hard into my shoulders. I’d nearly forgotten about it, a sea creature accustomed to its shell. I slide it off my back, sling it onto the bed. I leave my suitcase by the door. I can’t unpack yet. My denial. Maybe this is a vacation and I’ll fly back home in a few weeks to find my mom waiting for me.

She’s here, though, I realize. This is her childhood home. She slept under this roof until she fled at eighteen to Southern California for college. It gets me thinking.

I poke my head out, listen on the landing. Maura’s snoring rumbles in the distance like an idling car. A slow, moaning creak joins the chorus. The old house and the old woman settling in the night.

I creep down the narrow attic stairs to the third floor to find a sea of doors. Maura has so many rooms, so much space, and all closed doors. What’s hiding behind them?

To my right, a bathroom, vintage with a pull-chain toilet and a charming claw-foot tub. Directly across from the stairwell, I find a hobby room, cluttered with boxes, an ancient sewing machine, shelves overflowing with scrapbooking supplies. I can’t imagine Maura scrapbooking, and apparently neither can she--the first three albums I open are half-empty. And down the hall to my left, I flip on the light and find my mother.

Her room is frozen in midnineties glory, muted by the fine layer of dust covering everything, as though Maura shut it when Mom left for college and hasn’t been inside since. Her desk is dominated by a boulder of a computer, flanked by built-in CD shelving filled with bubble-gum pop, boy bands, and feminist folk. Posters on the wall offer a snapshot of the teen girl my mom once was: Romeo + Juliet, Jagged Little Pill, Titanic. So she liked Leo DiCaprio and was . . . angry?

I do a turn of the room, drink in the details, expecting, hoping, to feel a connection. A sensation that she’s watching over me, that she’s here. Everyone always says that, that you feel your loved ones with you. But I don’t. I feel suffocated. By this place that might as well be a mausoleum, by the gaping chasm of my own grief. These are only things, but they were hers. And they’re falling away to dust, like she did.

I’ve held it together in the weeks since my mom took her final breath. I didn’t even cry at the funeral.

But now, in my mom’s old room, in my creepy new house, I fling myself onto her mothball-scented, dusty bedspread, desperately hoping to catch one last whiff of her. And I cry all the tears I’ve refused to shed when I realize she isn’t there.

I wake with a start, disoriented, sweaty, and still in my street clothes. For a moment, the anachronistic setting confuses me, until it all floods back. I’m in my mom’s childhood bedroom. The nightmare is real.

The hall is blanketed with night. I should go back upstairs and go to bed, properly this time, but I’m parched. Careful as can be, I pad down the stairs on my way to the kitchen as moonlight streams through the warped windows. I find the glasses easily, fill one with water from a special tap attached to the farmhouse sink, and take a long draw.

The only sounds are the rhythmic croaking of crickets outside and the occasional snort from upstairs. There’s something magnetic about the house. I can’t resist the chance to explore unchaperoned. I take my water with me. The furniture is reduced to shades of gray in the night, but I pad around the first floor. I can make out a formal dining room, with an obscenely long table; a fussy sitting room, filled with knickknacks and china poised precariously in glassed-in cabinets. There’s a proper living room, with a giant TV and a comfy-looking couch--I’m relieved to learn that my grandmother isn’t the type of old person who refuses to own a television--and, tucked next to the stairs, a closed door. Quietly as I can, I slide the hulking wooden frame to the left and step into the most glorious space. I can make out wall-to-wall shelves of books. A desk in the center. A library? I should have brought my phone for light. Then I remember there are . . . you know, actual lights. I switch on a desk lamp.