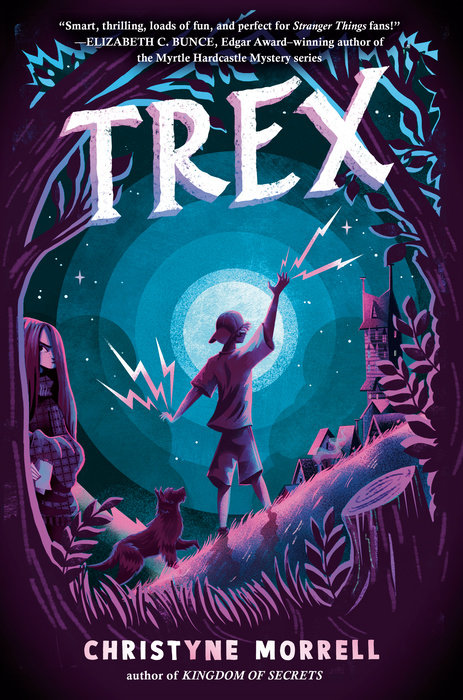

A thrilling mystery packed with adventure, secrets, and high-stakes danger! A boy with a cutting-edge brain implant and a reclusive girl training to be a spy must outsmart school bullies and take on a sinister corporation that’s hacking minds. Perfect for summer reading!

"Original, exciting, and chock-full of mysteries for the reader to unpack, Trex has all the makings of a hit."—Wesley King, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Wizenard Series

Trex’s experimental brain implant saved his life—but it also…

A thrilling mystery packed with adventure, secrets, and high-stakes danger! A boy with a cutting-edge brain implant and a reclusive girl training to be a spy must outsmart school bullies and take on a sinister corporation that’s hacking minds. Perfect for summer reading!

"Original, exciting, and chock-full of mysteries for the reader to unpack, Trex has all the makings of a hit."—Wesley King, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Wizenard Series

Trex’s experimental brain implant saved his life—but it also made his life a lot harder. Now he shocks everything he touches. When his overprotective mother finally agrees to send him to a real school for sixth grade, Trex is determined to fit in.

He wasn’t counting on Mellie the Mouse. She lives in the creepiest house in Hopewell Hill, where she spends her time scowling, lurking, ignoring bullies, and training to be a spy. Mellie is convinced she saw lightning shoot from Trex’s fingertips, and she is Very Suspicious.

And she should be . . . but not of Trex. Someone mysterious is lurking in the shadows . . . someone who knows a dangerous secret.

An Excerpt fromTrex

Chapter 1

Trex

I don’t expect the fireworks, but I have to admit, they’re pretty cool. All bright blue and crackly. Under different circumstances, I’d be impressed with myself for having made them. But under these circumstances--the ones I’ve been stuck with for as long as I can remember--it’s anything but impressive. It’s downright dumb. If Mom were here, she’d yank me out of this garden in a flash for making such a spectacle of myself. In fact, she’d probably yank me out of this town altogether and squish my dream of ever being a normal kid. Normal kids don’t shoot fireworks out of their fingertips.

But I’ve never been very good at “normal.”

Lucky for me, Mom’s not here. Nobody is. I whip my head around to make sure the coast is clear, then sigh in relief. Only Barnaby saw what just happened, and he’s not telling because . . . well, he’s a dog. He stares at me with his head cocked in confusion. He wasn’t expecting fireworks, either.

“Don’t give me that look,” I tell him. “That…

Chapter 1

Trex

I don’t expect the fireworks, but I have to admit, they’re pretty cool. All bright blue and crackly. Under different circumstances, I’d be impressed with myself for having made them. But under these circumstances--the ones I’ve been stuck with for as long as I can remember--it’s anything but impressive. It’s downright dumb. If Mom were here, she’d yank me out of this garden in a flash for making such a spectacle of myself. In fact, she’d probably yank me out of this town altogether and squish my dream of ever being a normal kid. Normal kids don’t shoot fireworks out of their fingertips.

But I’ve never been very good at “normal.”

Lucky for me, Mom’s not here. Nobody is. I whip my head around to make sure the coast is clear, then sigh in relief. Only Barnaby saw what just happened, and he’s not telling because . . . well, he’s a dog. He stares at me with his head cocked in confusion. He wasn’t expecting fireworks, either.

“Don’t give me that look,” I tell him. “That was your fault.”

Barnaby had lunged at something--a squirrel probably--and since I’m on the other end of his leash, he pulled me right along with him. I had no choice but to reach out for balance, and the only thing nearby was a statue--a bronze figure of a girl standing guard in the middle of the garden with one arm raised to the sky. I braced myself for the sting that happens every time I touch metal, like the snap of a rubber band against my skin. It’s annoying, but I’m used to it by now. It happens twenty times a day. But I’m definitely not used to fireworks.

“That was . . . weird,” I mutter, checking for burns and flexing my fingers. They look the same as always--slightly red and calloused. You’d never know they just produced lightning. Or whatever that was.

If dogs can roll their eyes, that’s what Barnaby does next. Maybe he’s trying to remind me it was my idea to wander into that garden in the first place. It was my idea to put myself within zapping distance of all that metal just for a better view of Hopewell. Even the statue itself--looking down at me with a stern expression on her face--seems to think it was a bad move. Maybe she’s right.

But how could I resist? From that garden on the hill, the town of Hopewell is spread out below me like a picnic blanket. Like the opening credits of a TV show: houses lined up in neat rows, a leafy-green park, a cobblestoned town square. It’s perfect. I scan the landscape for a specific building--one that’s brick and boxy and not quite as beautiful as all that other stuff. Except to me. Because that boring brick box is Hopewell Middle School, and starting tomorrow, it will be my school. I roll the words around in my mouth like a Jolly Rancher. “My school.”

On TV, kids are always trying to avoid the place, but as far as I’m concerned, school is like Disney World and the go-kart track and the ice cream shop all rolled into one. It’s a land of brightly painted lockers, where I’ll roam the halls with my new friends, getting into mischief (the harmless kind, of course) while teachers wag their fingers at us. I’ll form lifelong friendships and learn important lessons and have “the best years of my life.” At least that’s how it is on my shows.

But most of all, I’ll be ordinary there. Not the homeschooled kid who spends all day with his mother. Or the kid who nearly died when he was little. Or the kid who technically did die, if only for a few seconds. Or--worst of all--the kid who does that weird thing with his hands. I’ll just be Trex. Plain and ordinary. It’s going to be awesome.

If I can pull it off.

If I can make it a whole day without causing a light show.

Which is why those fireworks are anything but cool. And if Mom finds out . . .

Barnaby nudges my leg. He’s right--it’s getting late. Mom will start to worry, and nothing is more hazardous to my normal life than a worried Mom. I guide Barnaby out of the garden with a nod to the statue. The metal shimmers in the setting sun like warm, gooey honey.

When I get home, Mom is sitting at our foldout kitchen table, surrounded by towers of unpacked boxes. She’s eating leftovers from the Plate of the Union Café, where she just finished a shift. She’s still wearing her ridiculous uniform--a crisp white shirt, blue suspenders, and a sparkly red bow tie. In every new town--and there have been lots of new towns--Mom finds work at the local diner. The quality of the food varies, but the outfits are always cringe-worthy and the puns are even worse: New Fork City. Mad Platter Café. Chew Chew Train. You get the idea.

“You’re back,” she says, like she’s surprised. Like she hasn’t been tapping her fingernails and waiting for the creak of the front door. “How was the walk?”

“Good,” I say. My voice sounds squeaky and unnatural. I wonder if Mom notices.

“Is everything all right, Trex?”

Yep, she notices. If I give her even the tiniest hint that I’m worried about starting school tomorrow, she’ll gladly call the whole thing off. And if I mention that I just created lightning out of thin air? Well, I might as well start packing right now. Static electric shocks are one thing. Fizzy blue fireworks are another. Pull it together, I tell myself. It was a fluke. She won’t find out. Everything is fine.

“Everything is fine,” I say. I pull on a pair of highlighter-yellow rubber gloves. We have them stashed all over the house, so I don’t accidentally shock Mom or Barnaby.

“Are you excited about tomorrow?” she asks. “Nervous?”

“No!” I blurt out. “I mean yes! I mean . . . no and yes.” I take a deep breath and start over. So much for playing it cool. “Nervous: no. Excited: yes.”

“Uhhh, okay.” She narrows her eyes. She’s on to me. “Everyone gets nervous on the first day of school, Trex. It’s perfectly normal.”

There’s that word again: “normal.” What normal kid has to worry about setting fire to his math homework? And don’t even get me started on chemistry lab.

Mom smiles, but this time, I’m on to her. She’s waiting for me to crack. Like a criminal on a cop show, sweating under the hot lights in a police interrogation room. “How about a round of Alphabetter?” she asks.

Alphabetter is a game we invented years ago, to cheer each other up. And to calm each other down. The first time we played, we were in a cheap hotel in Albuquerque with a broken TV and no internet. Or was it Phoenix? Either way, it was someplace hot. To make ourselves feel better, we took turns naming our favorite things in alphabetical order. It’s hard to be upset when you’re making a list of things you love. But if I agree to play now, she’ll know I need it. She’ll know something’s wrong.

“No thanks,” I say. “I’m good.”

Instead, the three of us curl up on the couch and watch TV in silence. Well, not exactly silence. I’m wrapped in a rubber blanket, and it makes an annoying squelchy sound every time I move. I’m also resting my head where I can hear both of their heartbeats. Mom’s is slow and steady like a rocking chair. Barnaby’s thumps around like a tennis ball loose in a closet. Both are comforting in their own way.

One of my favorite shows is on--a hidden camera show where kids play pranks on unsuspecting grown-ups--but I’m too distracted to pay attention. I recite tomorrow’s strategy in my head one more time: Release excess charge as often as possible. Keep my keys within reach at all times. Never remove my lucky baseball cap. Avoid handshakes and high fives. . . .

I have to get it right tomorrow. I can’t get caught off guard again.

I add a new rule to the list: Absolutely, positively no more fireworks.

Chapter 2

Mellie

When people are doing something they don’t want to get caught doing, they look left and they look right, but they never look up. That’s why I’ve got such an impressive collection of other people’s secrets. Like the time I saw Mr. Patterson pick his nose and wipe it on his fancy gray pants. Or when I spied Isaac Burns kissing Arabelle Jones behind the rosebushes. I’ve never seen a murder or anything like that, but I’ll bet even Sherlock Holmes had some pretty dull cases when he was twelve, like The Mystery of the Missing House Keys or something. Even the best of us have to work our way up.

Lucky for me, I live at the peak of Hopewell Hill, with the best view in town. My house is a crumbling old dinosaur, but it’s three stories high, and my room is all the way at the top. It used to be the attic before I claimed it. I wanted to be the tallest thing in Hopewell, to see everything there was to see, so I pushed aside the old boxes, swept up the cobwebs, and made it my own. It’s still a little musty, but it has room to spare, and it doesn’t look so gloomy now that Mother painted it yellow. (The particular shade gives me a headache, but she swears it’s the most cheerful of colors.)

I know how I must seem from down there--the girl in the shadows peering through her curtains at the world below, like a phantom from a creepy Victorian novel. I have half a mind to wear a flowing white dress and howl at the moon just to play the part. But someday, when I solve a really big case, people will nod and say, “Now it all makes sense. Good thing she honed those detective skills when she had the chance.” Until then, they’ll smirk and whisper about poor, reclusive Mellie the Mouse.

The real reason I’m stuck up here, though, is because I’m sick. Or sick-ly, you might say, since the doctors can’t pin down what’s wrong with me, let alone find a cure for it. That’s why I spend hour after hour staring down at the shiny bronze scalp of the statue in the center of the garden, the Unnamed Girl. She has a severe sort of face, with high cheekbones and thin lips that refuse to smile. Everyone else in town thinks she looks mean, but I quite like her.

Besides, you can hardly blame her for wearing a grumpy expression--she’s always getting stepped on. Climbing all the way up the raised arm of Unnamed Girl is the ultimate dare in Hopewell, even though one boy allegedly fell off and broke his leg. You’d think the threat of fractured limbs would keep kids from trying to scamper up the statue, but it actually has the opposite effect. Middle schoolers are like that, though--completely immune to reason.

Speaking of unreasonable, I was watching from my window the day Harrison Palmer tried to make the climb. With his minions cheering him on, he scaled the statue all the way to her waist, as the hot, slippery metal tried to send him sliding back down. Even from where I stood, I could see the panic in his eyes as he glanced down at the solid ground seven feet below him. Conveniently for him, the Sweeney twins’ mother called them home at just that moment and Ridley Duncan discovered something on her phone more interesting than Harrison’s antics. As soon as he realized he no longer had an audience, Harrison whooped and triumphantly scooted down the statue’s skirt. At school the next day, he boasted to everyone that he’d climbed all the way to the top, stared into the empty eyes of the Unnamed Girl, and given her frozen hand a high five. Ridley stood beside him, confirming his harrowing story. Even the Sweeney twins--who were nowhere near the statue at the time--nodded along like lemmings.

Meanwhile, I knew the truth, but I didn’t say a word.

Because I don’t just collect secrets. I keep them, too.

But the boy walking beneath my window doesn’t strike me as the type with anything to hide. He must be the new kid, the one who moved into the blue house down the hill with the white picket fence. He looks about my age, with white skin and sandy hair that sticks out the sides of his baseball cap. He’s wearing a T-shirt, basketball shorts, and sneakers. In other words, he’s entirely unremarkable. Just like his dog--a beast so mutt-like I can only classify him as a “dog.”

They wander into the garden and stare out at Hopewell, mesmerized. Then the unremarkable dog goes after a squirrel, and the boy reaches out to the statue for balance. Just as his skin is about to come into contact with the Unnamed Girl, a bright blue zigzag passes between his hand and her metal boot. A streak of light, like a spark. Only bigger. Much bigger.

A firework.

I gape out the window, not even bothering to shrink behind the curtains. Am I really seeing what I think I’m seeing?

I must be. My eyes never play tricks on me. They’re my most reliable body part.

The boy wiggles his fingers, and the spark dances along the edge of the statue’s boot, like a jagged snake charmed by his fingertips. When he lifts his hand, the light grows to almost a foot in length, sputtering and hissing and changing shape. The boy doesn’t flinch or yelp in pain, and I can’t tell if he’s terrified or pleased with himself.

I reach for my notebook. But what do I write? What am I watching?

The boy curls his fingers into his palm, and just as quickly as the light appeared, it dissolves. The new kid seems rattled but not as much as he should be. Why isn’t he freaking out? With a parting nod to the Unnamed Girl, he and his mutt march out of the garden.

I stare at the statue for thirty minutes after that, waiting for her to do something. To burst into flame or come to life or . . . something. But she doesn’t. So I pace the length of my room, thinking. There has to be some logical explanation for what I just saw, some secret this boy is hiding. Maybe he’s not so unremarkable after all. The new kid is a mystery waiting to be solved--and solving mysteries is what I do best.