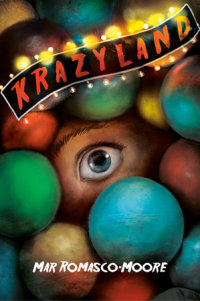

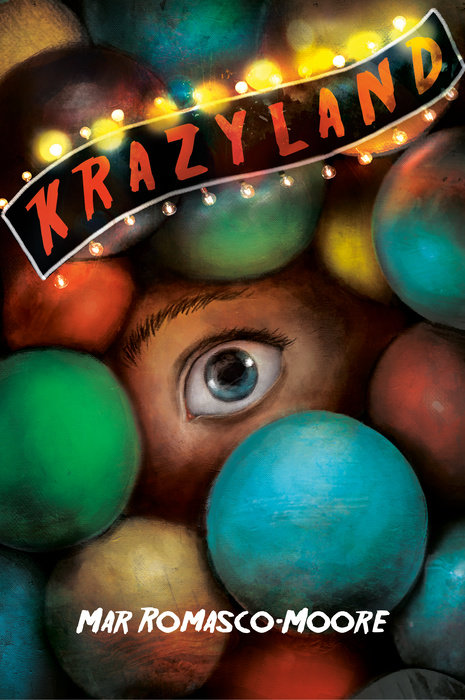

Krazyland

Author Mar Romasco-Moore

In this scary story for fans of Neil Gaiman, The Last Kids on Earth, and Goosebumps, the only way out is krazier than you could ever imagine...

Nathan used to be terrified of Krazyland when he was a young kid.

Now that he's 12, the spooky-themed arcade games aren't that bad. He even enjoys stomping on plastic spiders and battling a creepy doll with big plastic eyes. But things become scarier again when kids start to go missing from the entertainment park...

There's another world exists beneath Kraztown's ball pit. A world where the entertainment park's games come to life. And if he isn't careful, Nathan is going to be the next one sucked under!

An Excerpt fromKrazyland

Unhappy Birthday

There was icing in my nose. Icing in my eyes. Vanilla buttercream, with blue and purple roses. Though the roses were all smashed beyond recognition now.

I couldn’t see, but I could hear the cackling of my older cousin Jake, the one who had just shoved me face-first into a cake, and the indignant shrieks of my younger cousin Jenny, whose name had been written on said cake. I would happily have given up all cake for the rest of my life in exchange for instant transportation to anywhere else in the world.

I hadn’t even wanted to come to this birthday party. Nothing against Jenny personally, but she was four years younger than me, and so were most of her friends. I was thirteen, much too old to hang out with fourth graders.

I pushed myself up and wiped the icing from my eyes. Jake was smirking at me. He was three years older than me and at least a foot and a half taller, and he never let me forget either…

Unhappy Birthday

There was icing in my nose. Icing in my eyes. Vanilla buttercream, with blue and purple roses. Though the roses were all smashed beyond recognition now.

I couldn’t see, but I could hear the cackling of my older cousin Jake, the one who had just shoved me face-first into a cake, and the indignant shrieks of my younger cousin Jenny, whose name had been written on said cake. I would happily have given up all cake for the rest of my life in exchange for instant transportation to anywhere else in the world.

I hadn’t even wanted to come to this birthday party. Nothing against Jenny personally, but she was four years younger than me, and so were most of her friends. I was thirteen, much too old to hang out with fourth graders.

I pushed myself up and wiped the icing from my eyes. Jake was smirking at me. He was three years older than me and at least a foot and a half taller, and he never let me forget either of those facts.

“Now, what’s all this?” My uncle Steven appeared at the door to the party room with a stack of paper plates. Jenny ran over to him, wailing, and tugged on his beige staff T-shirt.

“Nathan fell in the cake,” said Jake.

Uncle Steven gave him a skeptical look, but there was little hope he would take my side. Jake was his son, after all.

“Go cover the front desk for a while” was all he said, waving a hand.

My uncle owned this place, and Jake was working here over the summer. No doubt I’d have to work here someday, too. Uncle Steven bought it two years ago, and since then practically every family event has been held in the neon-painted party room.

My uncle could at least have owned a normal business. Maybe an ice-cream shop or a movie theater, so I would benefit from unlimited soft serve or free matinees.

Instead, he owned Krazyland.

Stealthy Vegetables

Krazyland Kids Indoor Playplace was, according to a sign in the lobby, “the perfect space for kids to get the exercise they need while having the fun they crave,” which made it sound like one of those fruit juices that have pictures of strawberries on the front but are actually like 75 percent pureed carrots.

It was a converted warehouse. Half the building was filled with mechanical games that spat out tickets you could swap for cheap plastic prizes. The other half was filled with a maze of giant plastic tubes that looped around and around like the multicolored guts of a giant.

I’d been there a few times before my uncle bought it--for instance, in second grade, when this guy Kyle invited the entire class to his birthday party. I remember he looked vaguely disappointed when I showed up. No doubt it had been his parents’ idea to include everybody, even the kids Kyle didn’t particularly like.

Kids like me.

The owner back then had been an old guy with a gray beard and weird glasses. I could remember turning in my tickets to him at the prize counter once.

“I see great promise in you, young man,” he said as he handed over my beanbag frog. “Do not be discouraged if the world does not fit you.”

I blinked at him, too confused to respond, and then scurried off to hide in a corner until Kyle’s birthday party was over.

When Uncle Steven did buy the place--I think that old guy had died or something--my parents assumed I’d be delighted. I could get in free now, after all. They thought I’d want to go every day.

True, I enjoyed some of the arcade games, though many of them had bad graphics or fiddly controls. A lot of them--like the claw machines, which held the same junk as the bottom shelf of the prize counter--were also just blatant cash grabs.

The Skee-Ball lanes and the spider-stomping game were all right. And the tubes and trampolines had been fun when I was younger.

But at the end of the day, Krazyland was just too loud, too crowded. Too full of the bane of my existence: other kids. I was much happier at home, where it was safe and quiet. If it was up to me, I’d spend all my time in my room, alone, playing Voidjumper.

Escape

The morning of Jenny’s party had been perfect. It was summer. No school. No responsibilities.

I rolled out of bed and went directly to my computer.

Fifteen minutes later, I was running for my life, pursued by ten flying eyeballs.

I didn’t dare stop to look at them, but I knew they were there. Big white blobs the size of my head, trailing optic nerves like tails. Bright green laser beams shot from their pupils, barely missing me as I dodged and swerved.

I skidded around the corner and down the next hallway.

This world was all one big house. Endless, without windows. Plenty of doors, though.

I opened one at random. Beyond it was yet another hallway, with hideous procedurally generated wallpaper. I sprinted until my energy failed.

The next door I flung open led to a kitchen. I opened every cabinet, searching for a way out of the world.

The green light of the eyeball lasers pierced through the doorway.

I tried the refrigerator. A takeout container on the top shelf yielded a mysterious specimen, which I popped into my inventory to investigate later.

The first eyeball burst into the room. I yanked the lid from a pot on the stove and held it up as a shield. Just in time. The lasers deflected harmlessly.

I was just about to run again when I spotted it. There, revealed when I’d pulled off the lid: inky blackness, a hint of stars. The void, floating in a soup tureen.

The other nine eyeballs had crowded into the kitchen now, their lasers lighting the room up like a disco. I climbed atop the stove, thankful that I still had a shrinking potion in my inventory. I drank it, jumping at the same time. A laser swept the space where my head had been an instant before. I fell into the pot.

And kept on falling right out of the world, into the void.

“Nathan!”

My mother’s voice startled me so much I dropped the controller. I fumbled for it and hit pause.

“You haven’t even had breakfast yet,” Mom said from where she stood in the doorway, disapproval radiating off her in waves.

“It’s summer break,” I said.

She sighed. Last summer, I’d spent almost every day playing Voidjumper. I’d visited hundreds of worlds, solving puzzles and collecting items to bring back to my base world, which I’d built into a perfect digital paradise, just for me.

“You need to get ready,” she said. “We’re leaving in an hour.”

I’d forgotten all about the party.

“Aw, come on,” I said. “Do I really have to go? Jenny probably doesn’t even want me there.”

“Family is important, Nathan.”

“Okay, sure,” I said, frantically trying to come up with an argument that would appeal to Mom. I was good with words--it was my main line of defense. “But remember that time I sprained my ankle on the trampolines? Krazyland is just too dangerous. Surely, you would not be so heartless as to expose your one and only precious baby boy to certain grievous bodily harm?”

Mom merely raised an eyebrow. I was losing.

“I’m just saying it would be far safer for me to stay home,” I grumbled.

“Seventy-five percent of accidents requiring hospital visits occur in the home,” said my mother flatly. “It would be safer for you not to.”

Lost . . .

Which was how I’d ended up here, in the Krazyland bathroom, scraping cake crumbs out of my hair. I tried to reassure myself that it could be worse. At least I was better off than my best friend, Rudy, whose parents shipped him off to camp every summer. He’d texted me yesterday:

help bugs everywhere

no signal except in 1 spot

everybody fights 4 it

I may not survive

As far as I could tell, camp was like school but worse. Most of the “fun” activities sounded suspiciously like gym class. At least with school you get to leave every afternoon. At camp you’re stuck, surrounded by other kids twenty-four seven. No escape.

If only there were a void in every pot.

I eyed the bathroom door. What if when I opened it, it didn’t lead to Krazyland? I closed my eyes, concentrated every ounce of my will on wishing hard, and flung the door open.

I was greeted by the piercing screams of small children and the wafting scent of greasy pizza.

Still here.

The door trick never worked, of course, no matter how many times I tried it. And I’d tried it a lot, with many different doors.

Alas, the door to the boys’ locker room at school only ever led directly to gym class. At least the trick of pretending to have a stomachache so I could go to the nurse’s office worked some of the time.

I tracked down Uncle Steven in the small kitchen. Krazyland offered pizza by the slice and fried chicken wings by the bucket. Uncle Steven himself prepared these items. I say prepare instead of cook because all he did was dump them out of the box they came in directly into the deep fryer or the microwave.

“Hello, esteemed ancestor,” I said, sidling up to my uncle. “Terribly sorry to bother you, but I seem to be suffering a modicum of digestive distress.”

“Uh-huh,” he said, without turning. I’d expected more of a response than that. I’d even busted out several advanced vocabulary words. Adults usually ate up that kind of thing.

“I think perhaps I’d better go home right away to convalesce.”

He shot me a harried look. “What are you talking about?”

Before I could try again, a woman appeared at the ordering window with a sour expression.

“Excuse me,” she said to Uncle Steven, and then again, louder, without waiting for him to respond. “EXCUSE ME.”

“Yes?”

“I can’t find my kid.”

He pointed to a small sign posted just below the menu beside the ordering window, one of many such signs posted all over the building.

it is not our responsibility to watch the children said the sign.

“Yes, fine,” said the woman, “but we’ve got taekwondo in fifteen and I can’t find Brayden anywhere.”

Uncle Steven pulled a walkie-talkie from his belt, pressed a button. His announcement crackled over the loudspeaker: “Would Brayden please report to the kitchen area.”

He went back to work disaffectedly jiggling the deep-fryer basket. The woman remained at the window, shifting impatiently from foot to foot, scanning the playroom beyond, checking her watch, clearing her throat. Uncle Steven sighed.

His eye turned, regrettably, to me.

“Nathan,” he said as my heart sank, “how’d you like to be a big help?”

. . . And Found

I’m too old for this, I thought, as five-, six-, seven-, and eight-year-olds went careening past me, high on sugar, practically levitating with hyper glee.

In truth, the twisting tubes had once been my favorite part of Krazyland. I liked the way you could get totally lost in their mazes.

But even though I was still short for my age, they felt so much smaller and more cramped than they had just a few years earlier. The hard, curved plastic was murder on the knees, and I’d already been kicked twice. I was also faintly worried someone from my school might see me crawling around in here and deem me even more uncool than I was already.

The blue tunnel I was crawling through slanted suddenly downward. I slid, landed in the second-biggest ball pit. There were three kids in there already, all of them slinging balls at each other’s heads. As soon as I got to my feet I was struck in the ear with a deafening thwack of hollow plastic.

“Are any of you named Brayden?” I shouted amid a hail of plastic projectiles.

When there was no answer, I picked up a ball and whaled it at the nearest kid’s head. He ducked, vanishing below the surface before popping up again a few feet away and throwing another ball at me.

The lady had given me a description of her missing kid: age six, blond hair, striped shirt, blue shorts, “adorable.” None of these kids matched, so I waded laboriously out of the pit, pelted from all sides.

After that, I circled around to the smallest ball pit. It appeared empty.

“Brayden,” I shouted just in case, “your mom left. She said to tell you she doesn’t want you anymore and you can just live here from now on.”

When several moments passed with neither a cry of dismay nor a whoop of joy, I moved on to the largest ball pit. It was way in the back of the building, near the entrance to the stockroom, and about the size of a small swimming pool.

“Hey, everybody,” I shouted, “there’s free pizza for the first ten people who show up to the dining area. Better hurry!”

My lie emptied the ball pit in no time. I scanned each kid who scrambled down the foam steps. No striped shirt. I was about to turn away when a sound made me pause. I stared hard at the surface of the ball pit.

And there it was. Ever so slight, a shifting. Just the barest hint of movement over at the far end of the pit, a few balls settling.

I climbed the foam steps and waded in. Walking through plastic balls is surprisingly hard. Halfway across I hit a weird spot. There must have been a hole in the mesh at the bottom of the pit or something because I took a step and felt my foot sinking. I flailed, unbalanced.

“Arrgh,” I cried, gripped with a brief panic. My foot was stuck, somehow.

On the other side of the pit, a kid with blond hair and a striped shirt emerged in a sudden explosion of balls. He made a run for the nearest tube. With one enormous burst of effort, I wrenched my foot free of whatever was holding it and lunged at the escaping figure, managing to snag the back of his shirt with one hand.

“Brayden?” I asked.

“No,” he said, “I’m a shark.”

“Your mother is looking for you. Come on.” I dragged him toward the foam stairs.

“No!” he cried, wriggling mightily. “I hate taekwondo. They kick you.”

“Who does?”

“The other kids.”

“Well, kick them back. Isn’t that the point?”

“I’m scared,” he wailed.

“If we didn’t do the things we’re scared of,” I said, “we’d never do anything at all.”

I felt silly as soon as the words left my lips. It was something my mother said to me. I’d always thought it was dumb, so why was I repeating it?