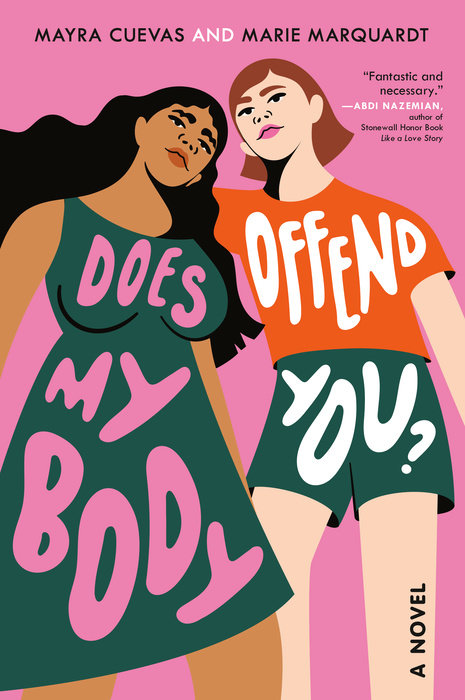

Does My Body Offend You?

Author Mayra Cuevas Marie Marquardt

Does My Body Offend You?

A timely story of two teenagers who discover the power of friendship, feminism, and standing up for what you believe in, no matter where you come from. A collaboration between two gifted authors writing from alternating perspectives, this compelling novel shines with authenticity, courage, and humor.

Malena Rosario is starting to believe that catastrophes come in threes. First, Hurricane María destroyed her home, taking her unbreakable spirit with it. Second, she and her mother are now…

A timely story of two teenagers who discover the power of friendship, feminism, and standing up for what you believe in, no matter where you come from. A collaboration between two gifted authors writing from alternating perspectives, this compelling novel shines with authenticity, courage, and humor.

Malena Rosario is starting to believe that catastrophes come in threes. First, Hurricane María destroyed her home, taking her unbreakable spirit with it. Second, she and her mother are now stuck in Florida, which is nothing like her beloved Puerto Rico. And third, when she goes to school bra-less after a bad sunburn and is humiliated by the school administration into covering up, she feels like she has no choice but to comply.

Ruby McAllister has a reputation as her school's outspoken feminist rebel. But back in Seattle, she lived under her sister’s shadow. Now her sister is teaching in underprivileged communities, and she’s in a Florida high school, unsure of what to do with her future, or if she’s even capable making a difference in the world. So when Ruby notices the new girl is being forced to cover up her chest, she is not willing to keep quiet about it.

Neither Malena nor Ruby expected to be the leaders of the school's dress code rebellion. But the girls will have to face their own insecurities, biases, and privileges, and the ups and downs in their newfound friendship, if they want to stand up for their ideals and––ultimately––for themselves.

An Excerpt fromDoes My Body Offend You?

Chapter One

Malena

I’m not a superstitious person, but my abuela Milagros says catastrophes come in threes. I’m starting to believe she’s onto something.

First came this beast of a hurricane called María, which caused our Island more devastation than we can mentally process. Mami and I are now stranded in the swampland that is Florida--our second stroke of bad luck. (The only upside is I get to hang out with my cousins every day, instead of just once or twice a year.)

And now, because irony is Lady Fortuna’s weapon of choice, thanks to those very cousins, my mala suerte trifecta may be complete.

How do I avert this third disaster looming over me before it wrecks what’s left of my life?

I reach for the medal of La Virgencita hanging around my neck, which Abuela says protects me from the mal de ojo. A cold chill runs down my spine as I step back from the full-length mirror attached to my bedroom door. I don’t know which sight is more pitiful, my reflection or the mishmash of secondhand furnishings…

Chapter One

Malena

I’m not a superstitious person, but my abuela Milagros says catastrophes come in threes. I’m starting to believe she’s onto something.

First came this beast of a hurricane called María, which caused our Island more devastation than we can mentally process. Mami and I are now stranded in the swampland that is Florida--our second stroke of bad luck. (The only upside is I get to hang out with my cousins every day, instead of just once or twice a year.)

And now, because irony is Lady Fortuna’s weapon of choice, thanks to those very cousins, my mala suerte trifecta may be complete.

How do I avert this third disaster looming over me before it wrecks what’s left of my life?

I reach for the medal of La Virgencita hanging around my neck, which Abuela says protects me from the mal de ojo. A cold chill runs down my spine as I step back from the full-length mirror attached to my bedroom door. I don’t know which sight is more pitiful, my reflection or the mishmash of secondhand furnishings around me--mostly donations from a local church drive for María evacuees.

This is bad. The skin on my back has gone from brown to angry red. The color of a Caribbean lobster that’s just been pulled from a pot of scalding water. It turns out bathing suits make for terrible landscaping apparel.

Yesterday, after my cousin Soraida back-talked Tía Lorna one too many times, we--because Tía Lorna sees me as an accessory to my cousin’s shenanigans--were forced to clean and mow their backyard. All afternoon, I pruned bushes while the sun literally licked my back.

My cousin Carlos went shirtless too, but somehow he managed to get a great tan. It’s so annoying that guys don’t have to worry about their boobs hanging out. Or about how to fall asleep if you can’t lie on your back.

I bet Carlos slept like a baby last night.

Not me. I barely slept at all. Lying on my stomach was pure torture, thanks to the two mountains that have recently risen from my chest. No one told me that double D really stands for doble dolor--double the pain.

Where did these things come from, anyway? Besides Soraida, I don’t know many other fifteen-year-olds that have to shop for “big bust bras.” My abuela says the Rosario women were all blessed with the precious “gift” of “tetas grandes”--a clear sign of our female strength, she reassures me.

“Wear them proudly,” she loves to say.

But this morning, they feel more like an enormous inconvenience than a gift.

Mami knocks on my bedroom door and peers in.

“You ready, nena? I can’t be late. They’re short-staffed at the ER,” she says in Spanish.

It’s a small comfort that, at home, we only speak in our mother tongue--Puerto Rican Spanish.

Mami opens the door a little wider. Her scrubs are covered in palm trees and flamingos standing on one leg. They’re what my cousin Soraida mocks as “Florida chic.” Mami says the kids at the pediatric ER where she works love them. The cute pink birds apparently help ease her patients. I wish they would do the same for me.

“There’s no way I can wear this.” I drop the bra dangling from my fingers onto the bed. “It stings.” I turn so she can get a better view of my back.

Mami walks in and sits on my bed. She pulls a penlight from a pocket in her top and aims it at my skin, inspecting at close range.

“You have first-degree burns,” she says in her no-nonsense medical voice. “Did the pomade we spread on last night not help?” She picks up the white tube on my nightstand and reads the label. “I’ll bring you something stronger from the hospital.”

Then, switching to her other no-nonsense voice, that of the Puerto Rican mother, she adds, “I told you to wear sunscreen.”

“I couldn’t find it.” I jerk away, trying to hold back the wave of irritation that washes over me.

For four years, Tía Lorna has harped on and on about the virtues of life in Florida. “People really know how to live here,” she likes to say. “The government gets things done. The people are not a bunch of vagos and sinvergüenzas. There’s plenty of money for anyone willing to work hard.” Tía could sell the American Dream to the gringoest of gringos.

I never thought my parents would fall for Tía’s Disneyfied depictions, but that was Before María--before a category 5 hurricane uprooted our lives and replanted us 1,200 miles away from home. After María, they bought the dream, hook, line, and sinker.

The weekend of Abuela Milagros’s seventieth birthday, Mami and I flew to Jacksonville to celebrate, vaguely aware that another hurricane was barreling toward the Island. Papi was supposed to come with us, but he works as a local supervisor for the Federal Emergency Management Agency. It had only been ten days since Hurricane Irma skirted Puerto Rico, blasting the northeast coast with hundred-mile-per-hour winds. He had to stay behind to deal with Irma’s wreckage.

“There’s a prayer chain going around the world, mija,” Abuela said as we ate too-sweet birthday cake, watching María’s deadly approach from Tía Lorna’s living room. “See how Irma went away? Same thing is going to happen with María. Nothing to worry about. The prayers will keep the islita safe.”

They didn’t.

The prayers decidedly Did. Not. Work.

God just flat-out ignored us.

María wrecked the Island beyond recognition. And with it, she destroyed my life. A life filled with friends I’ve known since birth, a school where fitting in was easy and my teachers told me I was a “natural leader,” and a home with two loving parents. A life that I didn’t fully appreciate until it was gone.

We arrived in Jacksonville with one carry-on suitcase each. Mine was packed with a couple of cute dresses, my favorite strappy sandals, and a bathing suit, basically everything I needed for a birthday weekend.

Tía Lorna arranged a collection for us at her church, and now, as a result, we have two single beds, a couch, a coffee table, pots and pans, tableware, and a brand-new fondue set. We’re still considering what to melt first: cheese or chocolate. Tough decision.

Through the church’s connections, Mami landed a job as a physician assistant at a local hospital’s pediatric emergency room. Tía was quick to point out that she’s making more money here in Florida for the same work that she was doing back home. “Money isn’t everything,” I tried to argue. But given our current state, everyone ignored me.

I enrolled in the same high school as my cousins. And Papi is still in Puerto Rico. God only knows when we’ll all be together again. No use praying for any miracles, I guess.

“I can’t go to school like this,” I protest, waving my hands in front of my bare chest in an exaggerated gesture.

“They’re just breasts, Malena. Everyone has them.” Mami rummages through the few items hanging in my closet. There’s not much to pick from. In hindsight, I did an awful packing job, even for a five-day trip.

“All of my stuff is dirty,” I remind her. Which is how I ended up wearing my one-piece bathing suit with the scooped back to rake grass clippings. Our new apartment doesn’t have a washer-and-dryer hookup--because, as we learned, this costs extra--so I’ll have to wait until next Saturday, our allotted laundry day at Tía Lorna’s. Our dirty laundry has literally become a source of family drama. The solution: alternating weekends, so that we don’t get in the way of Carlitos’s pristine baseball uniforms.

“You can wear one of my shirts,” Mami says, heading to her room. She returns with a flowery tunic that’s far too big for me.

“Can’t I just stay here?” I plead. “We still have a bunch of the church donations to unpack. I’m pretty sure I saw an ice cream maker somewhere.” I’m grateful for the kindness of all those strangers, but it’s funny, the things people think you will need to rebuild your life. “I can sort everything while you’re at work. Maybe make some homemade ice cream?”

“I don’t want you missing any more school.” She takes the tunic off the hanger and tugs on a loose thread. “You can’t afford to fall behind.”

“I’m doing fine,” I mumble.

“Lorna thinks that if you keep up your GPA and get more involved--”

I cut her off. “Tía Lorna has an opinion about everything.”

“I think she’s right about this. Between your grades and extracurriculars, you may be eligible for a full scholarship when you graduate. The next three years will go by fast, and the colleges here are expensive. It’s not like Puerto Rico.”

What is she talking about?

I look away, too overwhelmed by the same argument we’ve had every other day since we got the apartment. To me, our relocation is temporary. A Band-Aid to get us through the rebuilding efforts back home. Once our condo in San Juan is fixed and power and running water are restored, we’ll go back to the same contented existence we had before. An existence that included lazy afternoons on the beach at Ocean Park, those tropical fruit paletas you can only get in Old San Juan, and Sunday night family dinners at El Mesón de Pepe. If I close my eyes, I can almost taste the savory sauce in the mofongo de mariscos.

They say that the coquí frogs native to Puerto Rico can’t survive outside the Island. I’m starting to understand why. Every pore of my body longs for home.

That’s what I’m begging La Virgencita for every night.

My old life, just as it used to be.

Sure, I’ve dismissed any concept of an all-powerful, wish-granting God. But, strangely, I’m becoming the same sort of candle-lighting, rosary-praying, kneeling Catholic as my abuela and her mantilla-wearing friends. Talking to La Virgencita is different. For some reason, I still believe she cares.

“Raise your arms,” Mami says.

“It hurts,” I complain.

She gently slips the tunic over my head so that it doesn’t come into contact with my raw skin. “See? That’s not so bad. You can’t see anything.”

I turn left and right in front of the mirror, assessing my chest. The last thing I want is to become That Puerto Rican Who Doesn’t Wear a Bra. That would be so much worse than the person they already see: That Puerto Rican Who Lost Everything to María.

I’ll take Poor María Malena over Braless Boricua.

Miraculously, I manage to move through the morning unnoticed. I’ve kept my math and chemistry books continuously pressed against my chest as I make my way between classrooms.

By fifth period, I’m relieved to be halfway done with the day. I take my seat in Ms. Baptiste’s class, waiting for my cousin Soraida to walk in. When she does, she drops a granola bar and a banana onto my desk.

“I didn’t see you at lunch. Were you hiding your tetas in the library?” she asks with a smirk.

Find a Puerto Rican slang dictionary and look up the word candela, and next to it you’ll find a picture of Soraida. She’s loud-mouthed, brash, and unapologetic, and she completely lacks a filter. Her long mane of curly brown hair and big expressive brown eyes only add to the effect. On most days she’s a royal pain in the ass, but I love her anyway.

“I like hanging out in the library,” I tell her. “I miss my books.”

“You’re such a nerd, prima.”

It’s true. I love learning new things, especially in this class.

Originally, I signed up for video production because Soraida was in it, but I’m completely geeking out on cameras, composition, lighting, and storytelling.

And I adore the teacher, Ms. Baptiste. She’s always dressed in bold colors, with flashy gold earrings and a wrist full of bracelets. It’s oddly reassuring to be in her presence. Not only is she from Trinidad and Tobago, which practically makes us Caribbean neighbors, but she also shows some cool documentaries. Last week, we watched a short film titled He Named Me Malala, about a Pakistani teen who was shot in the face for speaking out to defend girls’ right to education. She was even awarded the Nobel Peace Prize--at seventeen!

Watching that documentary, I was in awe. In the film, Malala said remaining silent is like giving up, and we have to raise our voices to speak the truth. To quote a reggaeton song, that girl’s got babilla.

Ms. Baptiste calls it “owning your narrative.”

How can a girl who’s been through such a horrible experience turn her life into a message so powerful that it’s changing the world? I have no idea.

As for me, I’m just trying to stay quiet, keep my head down, and survive. At Sagrado Corazón, I was a doer. Here, I’m a spectator. Mostly binge-watching the documentaries Ms. Baptiste tells us about in class. Which makes me both a coward and a total nerd. I guess Soraida is right.

“Have you talked to your dad?” Soraida asks, turning to face my desk.

“For, like, a second last night. He’s running operations in the mountains.”

“Wait, how long is he staying there?” she asks, her eyes wide.

I shrug, trying to avoid the pity in her eyes. “As long as he’s needed.”

“How did he call you from way up there?” she asks.

“He borrowed a satellite phone from someone.”

“Doña Lucrecia, that vieja down the street, keeps going on and on about how her son calls her every day using a satellite phone.” Soraida pauses, clears her throat, and adjusts her voice so it’s high-pitched and nasal, like Doña Lucrecia’s. “Yo no entiendo. Why doesn’t everyone have one of those phones?” She curls her lips and pinches her nose as if something smells rotten around us. Her Doña Lucrecia impressions always make me snicker.

“She’s such a come mierda, that vieja,” she adds, her face falling back to normal. “Her son’s house didn’t have any damage. Of course it didn’t! The guy lives in freaking Montehiedra. Those mansions up on that hill are like fortresses.”

I let her ramble until she runs out of steam and possibly even forgets what we are talking about. I don’t want to think about Papi right now with a classroom full of strangers around me. Missing him hurts too much.

Ms. Baptiste calls for our attention, and I do my best to focus on class. It’s proven to be a good distraction from my island troubles. A few times a week she guides us through a meditation session. She says it can help us deal with stress and clear our minds. At first I thought it was a little woo-woo, sitting there in silence for ten minutes, watching our thoughts. But over time it’s become a release. For those ten minutes, the heaviness in my chest lifts, evaporating like fog at sunrise over the mountains of Cayey.