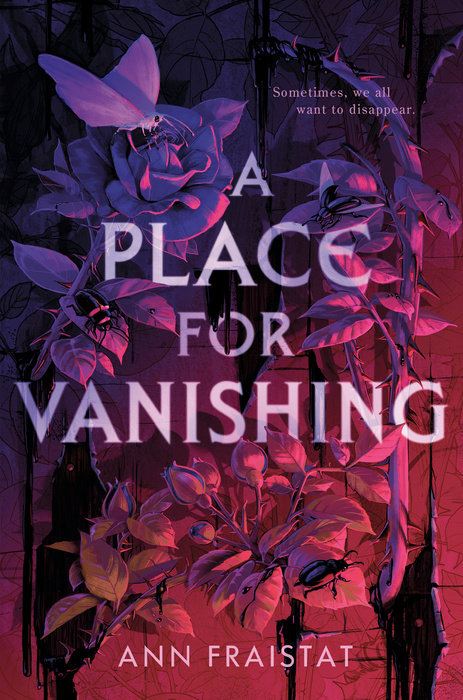

A Place for Vanishing

A teen girl and her family return to her mother's childhood home, only to discover that the house's strange beauty may disguise a sinister past, in this contemporary gothic horror from the author of What We Harvest.

The house was supposed to be a fresh start. That's what Libby's mom said. And after Libby’s recent bipolar III diagnosis and the tragedy that preceded it, Libby knows she and her family need to find a new normal.

But Libby’s new home turns out to be anything but normal. Scores of bugs haunt its winding halls, towering stained-glass windows feature strange, insectile designs, and the garden teems with impossibly blue roses. And then there are the rumors. The locals, including the mysterious boy next door, tell stories about disappearances tied to the house, stretching back over a century to its first owners. Owners who supposedly hosted legendary masked séances on its grounds.

Libby’s mom refuses to hear anything that could derail their family’s perfect new beginning, but Libby knows better. The house is keeping secrets from her, and something tells her that the key to unlocking them lies in the eerie, bug-shaped masks hidden throughout the property.

We all wear masks—to hide our imperfections, to make us stronger and braver. But if Libby keeps hers on for too long, she might just lose herself—and everyone she loves.

An Excerpt fromA Place for Vanishing

Chapter One

Days like this made me wish I’d never come back from the dead.

Since the doctors dragged me back six weeks ago, life sometimes felt foggy, like a strange dream. But nothing was stranger than this: sitting in Mom’s road-weary sedan, gaping through my window at the house towering over the yard, the street, our car. Us.

The house stared back.

The crumbling Queen Anne Victorian was massive. Solid. It sank into the earth like it had roots coiled five hundred feet down.

“Do you like it, girls?” Mom turned to me in the passenger seat and my thirteen-year-old sister in the back. Since I’d returned from the psych ward, her every word came glazed in honey. The way you might talk to a five-year-old—if you were bad with kids.

I couldn’t find the breath to answer her. I rolled down the window, that thin veneer between me and the house, inch by inch. The summer air climbed into the car with us, sticky and suffocating.

This was the house Mom had inherited from her parents? The one that Mom—a real estate agent—had ignored for decades? Had never even tried to sell?

I was stunned by the sheer size. The extravagance. The house had to be over a century old, with its spindly spires and lacy woodwork. In places, the white trim was still so shiny and marshmallowy that it hurt my teeth. But age and rot had left their marks, too. Faded cobalt paint encased the house’s shingled body, peeling like sunburned skin. Weathered wood boarded every window. It was like the place was guarding against a hurricane decades in the making.

And it was like the neighbors knew. Football-field-sized gaps sat between our property and the single-family ranch homes on either side. They hunkered low, less than half the height of our monstrosity.

The longer I stared, the more my chest tightened under my seat belt. The house’s steep rooflines towered with octagonal turrets and sharply gabled dormers, masking the layout inside. It felt like the kind of puzzle that if you stared long enough, revealed a whole new picture. One hiding smugly just under the surface. There had to be some reason it had sat empty so long. Maybe the neighbors and their flinching houses knew something I didn’t.

Worse, maybe Mom knew something I didn’t. All this time, she’d been holing us up in a two-bedroom apartment a couple counties over, and she’d made this place sound like some rinky-dink shack.

“Mom . . . ,” I said finally, “I thought you said this house was worthless.”

“No!” Mom hid her hands in her lap, tearing at her thumb’s cuticle. A habit I’d inherited, but she’d tried to kick, to set an example. “It wasn’t the best fit for us before, but I couldn’t have said ‘worthless.’ ”

She’d definitely said worthless. It was only since my stint in the hospital that Mom had started singing this house’s praises. Suddenly decided this was the place for us after all. Anything to get me into a new school before the fall crept up on us.

I looked over my shoulder at Vivi, hoping she’d help me call Mom out. She’d been there for the same conversations I had.

But she ducked my glance. “It’s great, Mom,” she said, though her chirping voice came out uncertain. A little thin. “Maybe we could check out the inside. Right, Libby?”

Likely, she was prodding me to play along for Mom’s sake.

And she was probably right—I should. For better or worse, this was our new home, and I wanted to love it. The old-timey embellishments weren’t without their charm. The size was astounding. I just couldn’t shake the strange sensation gnawing at my brain—that something was wrong.

Maybe it was me who was wrong.

I’d caused a lot of misery lately. I owed it to Mom and Vivi to make them feel good.

“Sorry, Mom. I was just surprised,” I lied dutifully. Once I adjusted to my new medicine, Dr. Glaser said it would get easier to smile. For now, I had to settle for a stiff flash of teeth and hope I didn’t look as much like a grinning skeleton as I felt. “Give us the grand tour.”

“The grand tour, yes,” Mom echoed with new life. A little color flushed back into her white cheeks, and she fluffed her shoulder-length brown curls like it was showtime. This time, I’d said the right thing.

I followed Mom and Vivi out of the car, past the white spiked fence.

On the cracked front walkway, I craned my neck until it twinged, peering at the house overhead. This place delighted in asymmetry. The whole thing felt unsteady, like any second it might topple down to crush us.

And yet I couldn’t look away. You didn’t take your eyes off a snake sizing up your ankle. Somehow, this place filled me with the same uneasy impulse.

“Don’t you love all this ornamental trim? That’s called ‘gingerbread’—isn’t that sweet?” Mom cooed, in full saleswoman mode. “And the yard needs some sprucing, but can you believe the potential?” She swept her arms around like the star of some musical, inviting Vivi and me to join her onstage.

We nodded, and managed the appropriate murmurs of admiration. But the yard was a patchy yellow, sun-dried to straw. Even the stray dandelions had been reduced to scraggly stems. Maybe it had been less bedraggled when Mom had lived here as a kid, but decades of neglect had amounted to decades of decay.

Strangely, the only plants thriving were the shaggy bushes that wrapped around the base of the house and the inner perimeter of the fence. Glossy leaves, blue buds. They pulsed with cicadas, buzzed with wasps. And they bloomed in the early July heat, oblivious to the steaming roads and sidewalks.

“Blue roses,” Mom told us, “if you can believe it. I don’t remember much from my time in this house when I was little, but those made an impression. Usually, florists have to dye roses blue. They aren’t supposed to grow in the wild.”

I glanced down the street, expecting to spot them in nearby yards if they were local to the area. But the rest of the block was all puffy popcorn balls of hydrangeas and cheery pink crape myrtles.

This tangle of impossibly blue roses was ours alone.

I examined the nearest bush, with its clusters of thorns and red-veined leaves. The petals, arranged in mesmerizing swirls, were velvety-soft against my finger but oddly thick for a rose. Almost meaty.

Floral perfume billowed into my nose, so heavy it was practically mind-altering.

I’d never seen or smelled anything like it.

Still, for Mom’s sake, I was grateful. She’d always had an appetite for gardening, swamping our old apartment patio with herbs and the poor tomato plants that died no matter what. A real yard like this could be the escape she needed.

And if Mom had couched those roses as a scientific anomaly to capture Vivi’s attention, then well played. My sister was practically buried headfirst in a nearby bush. Mom had to pry her away so we could continue our tour.

As she led us across the creaking wraparound porch to the front door, the moment of truth approached. The inside of the house might not feel as strange as the outside. I might even like it. Please, please, please.

The knocker was also a rose—a silver hunk the size of my fist. Its petals were rendered in breathtaking detail, thin and rumpled, the edges burnished with age. Custom-made. No doubt expensive.

It should make me feel better: Someone had once loved this place. It was possible to love this place.

Mom threw open the front door. “Welcome home, girls!”

We were greeted by a whiff of fresh lemon, one of Mom’s inviting real-estate-agent tricks.

But the second I stepped inside, a musty ripeness closed around me like a fist. Rotting logs and honeysuckle. Like under the skin of this wallpaper, the house’s guts were a pulpy mash of mothballs and mildew.

Light trickled in from the open door behind us, but beyond the cramped foyer, the house gaped as dim as a mouth. Not even the faintest rays slanted in through the windows.

It took me a second to realize why. The windows weren’t only boarded from the outside. They were boarded from the inside, too. I’d thought the point was to protect the house from the outside world, not the other way around.

Metallic dread gummed up the back of my throat, even as I fought it.

Vivi also hung back, hovering in the doorway behind me.

Mom winced at our lack of enthusiasm. “Uh, hang on!” She fumbled toward a floor lamp in the foyer, complete with droopy shade and dripping fringe. It flickered to life with all the conviction of a candle in a cave. “The windows were supposed to be uncovered by now. I’ll give the contractor another call.”

A brassy gleam caught my eye. Across from the front door, a plaque clung to the wall, mottled with oxidized patches. Its deep-etched lettering read: madame clery’s house of masks. est. 1894.

I squinted at the words, as if an explanation might appear if I stared hard enough. “Mom, what is this?”

“Oh!” Mom turned back, with an absent-minded smack to her forehead. Not like someone who’d actually forgotten their keys, more like someone who wanted to indicate they had. “Right. This house is something of a local landmark. Apparently, your great-great-great-granduncle and his wife were entertainers. So you’ll notice a bit of kitsch here and there.”

“What does it mean, though?” I asked. “ ‘House of Masks’?”

“Sweetie, that was . . . what? A century and a half ago? I can’t claim to know all the history.”

Mom had just called this house a local landmark. And she was a complete nerd about houses and their histories. Even if no one in the family had told her, did she really want me to believe she hadn’t looked this up?

She was avoiding my eyes again.

Guess I’d have to look it up myself.

The plaque lay on top of cloudy blue wallpaper. Past the dust, a faint gold glinted. I swiped away a palmful of grime to reveal a filigree design: Winding vines and bugs creeping through leaves. Beetles and ants and butterflies, centipedes and praying mantises . . .

If this is what Mom meant by kitsch, it wasn’t what I’d been expecting.

“Hey, this is kind of cool . . . ,” Vivi said, stepping closer to trace over the nearest gold caterpillar. A shadow of her old smile played across her face.

Vivi loved bugs. For years, Mom and I had prayed it was a phase, but now she was an up-and-coming teen and an aspiring entomologist.

Maybe she’d bond with this house after all.

I did want that for her—for her to find a new happy place—but if the house won her over, I’d be the only one with actual reservations. Yet again, the problem child.

My bare arms itched. The dust of this place was settling over me like a second skin.

“How long has the house been empty, Mom?” My voice came out small, muffled by what had to be a million rugs and drapes, sure as a hand clapped over my mouth. “Has anyone been in here since you and your—”