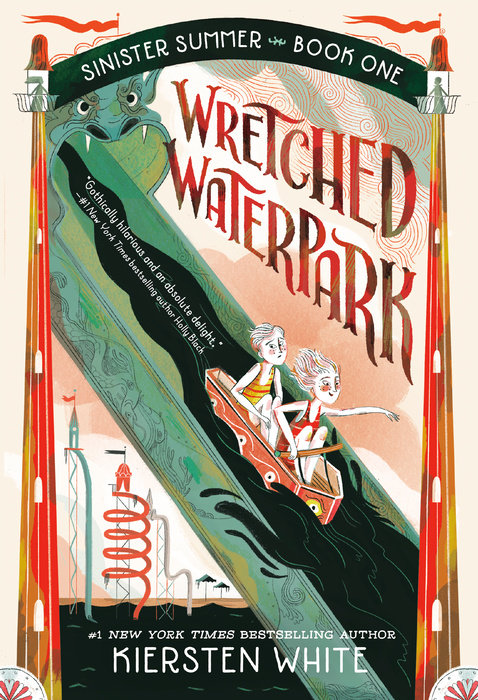

Wretched Waterpark

Wretched Waterpark is a part of the The Sinister Summer Series collection.

A middle-grade mystery series that's spooky, creepy, and filled with gothic twists! Meet the Sinister-Winterbottom twins, who solve mysteries at increasingly bizarre summer vacation destinations in the hopes of being reunited with their parents—or at the very least finally finding a good churro.

“An absolute delight. If I have to die in a waterpark, I want to die in this one.”—Holly Black, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Cruel Prince

"Wickedly weird. . . . Will appeal to anyone who loved A Series of Unfortunate Events." —The New York Times

Meet the Sinister-Winterbottoms: brave Theo, her timid twin, Alexander, and their older sister, Wil. They’re stuck for the summer with their Aunt Saffronia, who doesn’t know how often children need to eat and can’t use a smartphone, and whose feet never quite seem to touch the floor when she glides—er—walks.

When Aunt Saffronia suggests a week pass to the Fathoms of Fun Waterpark, they hastily agree. But the park is even stranger than Aunt Saffronia. The waterslides look like gray gargoyle tongues. The employees wear creepy black dresses and deliver ominous messages. An impossible figure is at the top of the slide tower, people are disappearing, and suspicious goo is seeping into the wave pool.

Something mysterious is happening at Fathoms of Fun, and it’s up to the twins to get to the bottom of it. The mystery, that is. NOT the wave pool. Definitely NOT the wave pool. But are Theo and Alexander out of their depth?

An Excerpt fromWretched Waterpark

Chapter one

Their aunt was decidedly Sinister.

But only because she was from their mother’s side of the family. If she had been from their father’s side of the family, she would have been decidedly Winterbottom. It had been a great trial for each of the Sinister-Winterbottom children to learn how to write their own names, something their usually thoughtful parents had neglected to think through.

Another thing their parents had neglected to think through was the wisdom of dropping off sixteen-year-old Wilhelmina Sinister-Winterbottom (who had actually learned how to write her own name as a toddler), twelve-year-old Theodora Sinister-Winterbottom (who had never to this day written out her whole name, preferring Theo), and also twelve-year-old Alexander Sinister-Winterbottom (who had always insisted on each and every letter of his entire name and would not answer to Alex even if he were hanging off the side of a cliff and a search party was frantically shouting it) to spend the summer with their aunt Saffronia Sinister, whom the children had never met, and who, by all appearances, had never encountered an actual human child before.

Wil had been adopted as a baby. Theo and Alexander had joined the family four years later, born hand in hand. Sometimes, still, when they weren’t paying attention or they were nervous or scared, they reached for each other’s hands.

They weren’t reaching for each other’s hands now, though, because they weren’t nervous or scared. Just confused. Their noses--with matching freckles dotted across quick-to-sunburn white skin--wrinkled in unison.

“Do you remember getting here?” Alexander whispered.

“What?” Theo answered, shifting closer to him. Her short, spiky brown hair was pushed back from her forehead with a headband. Alexander’s was neatly combed and gelled into place.

“How did we get here?”

“The kitchen?”

“No, this house, in-- Where are we? What town is this, Aunt Saffronia?”

But Aunt Saffronia spoke as though she didn’t hear Alexander’s question. “I wonder about your parents’ judgment, summoning me. I am not well suited to--” Aunt Saffronia gestured vaguely in their direction. “And I wonder if you will be suited to the grave tasks ahead. Still. They had no other options.”

“So you’re taking care of us. The whole summer.” Theo scowled.

Aunt Saffronia merely nodded. “How often would you say you need to eat? If I set out some food in the morning, will that be enough?”

“Depends on how much food you set out,” Wil answered, not bothering to look up from where she tapped furiously on the screen of her phone. Her fingers moved so fast, sometimes they blurred. Her phone’s name was Rodrigo, and it was her third-favorite member of the family. She always refused to say who were in first and second place, though, leaving Alexander vaguely worried that he came in after the phone. Theo was confident she was first and would not have believed it if anyone had told her otherwise.

“It also depends on what kind of food you set out,” added Alexander, who was very particular about food-safety protocols. Images of sweating cartons of milk going sour made him feel as though he were breaking out in a cold sweat along with the milk.

“Definitely not enough,” said Theo. “We need to eat at least as often as you do.”

Aunt Saffronia pursed her colorless lips. This statement seemed to puzzle her even more than trying to calculate how to feed three children. “Yes. As often as I . . . eat.”

Theo stomped past her and opened the fridge. It was empty. Apparently the food in question was theoretical. And theoretical food was Theo’s least favorite type. She even preferred beets over theoretical food, and all beets tasted like dirt.

Alexander was distracted from the theoretical food by the non-theoretical kitchen. It looked like it had been transported directly from an old TV show. The floor was black-and-white tile, the walls a warm marigold color, the cabinets and counters white like the old-fashioned fridge. Had he not still been vaguely queasy just thinking about spoiled milk, he would have appreciated how well the kitchen matched his aunt.

Aunt Saffronia looked a bit like she had been transported from another era as well. Her dress trailed on the floor, hiding her feet. Her hair was long and straight, nearly black, and her skin was so pale it blended in with the stark white cabinets. Her large eyes, which Alexander was fairly certain had not blinked once during this conversation, remained fixed on a point somewhere behind them.

“I could . . . buy some food?” she suggested. Alexander did not understand why it was a question and not a statement.

“Or you could order it,” Wil said, scowling at Rodrigo. If Aunt Saffronia never blinked, Wil never looked up from the shiny screen.

“How?”

“On your phone.”

Aunt Saffronia looked at an odd sculpture affixed to one wall. She picked up part of the sculpture and held it gingerly to her ear. It was, puzzlingly, a phone. Why was it on the wall? Why did it have that curly cord, like a leash keeping it in one place? Was it going to run away if it were set loose?

“Hello?” Aunt Saffronia whispered. “Is anyone there? Do you have food?”

Wil finally looked up. “I mean on your cell phone? Using the internet?” She shook Rodrigo meaningfully. Her fingernails were bright blue, her skin was dark brown, and her face held an expression Theo and Alexander both knew meant she was about to lose it. Their parents would have gently redirected her to the piano to slam out her anger on the keys, but their parents weren’t here, and neither was their piano, and neither was anything from home, because their parents had decided to ruin the entire summer.

Why? The kids had been roused from their beds in the middle of the night with urgency. Urgency and candles. A lot of candles. Why had their parents been lighting so many candles? Then--they were here. Alexander couldn’t quite fill in the blanks. Had they taken a car? An airplane? A train? Why couldn’t he remember?

But he remembered the worry behind his parents’ eyes as they tried to smile and promise the summer would be great. He couldn’t shake that same worry, like it had jumped from them to him, like it was connected to him with the same tangled, curling leash that kept the phone on the wall.

He didn’t think this summer would be great.

In the absence of a piano, Theo stepped in. She wasn’t worried. She was annoyed. She’d had big plans for this summer, and now they were all on hold. “Do you have a cell phone?” she asked, wanting to study the antique phone she had thought was merely decorative. The whole thing was absurd but kind of funny, and she wondered how it worked. “Or a computer?”

“What’s the Wi-Fi password? I can’t find a signal.” Wil’s fingers tightened around Rodrigo.

“Water park!” Aunt Saffronia said, a smile like a skull’s grimace on her face. “I’m taking you children to the water park. It’s the first task to be accomplished.”

“We have to accomplish a water park?” Alexander asked.

“What does ‘task’ even mean? Isn’t that like an assignment?” Theo chimed in. “Do you mean ‘activity’?”

“And besides,” Aunt Saffronia said, ignoring their questions once again, “children like water. And parks.”

“Does the water park have Wi-Fi?” Wil asked through gritted teeth.

“Does the water park have food?” Theo asked.

“Does the water park have strict food-safety protocols and an A rating from the local health department?” Alexander asked.

None of them asked if the water park was plagued with a series of mysterious disappearances, which would soon be much more important to them than Wi-Fi or lunch, but, in Alexander’s case, would still rank slightly below food-safety protocols.

Chapter two

“Here we are!” Aunt Saffronia sounded as relieved as the three Sinister-Winterbottoms felt as they tumbled out of her ancient metal beast of a car. She drifted along the roads in the same way she drifted through her house--distracted, never quite focused, and with an air of confused distance. None of which were ideal qualities in a driver.

Aunt Saffronia rolled down her window. Though the day was windy, her hair did not move. “Get the week pass. A week should be enough time.”

“Enough time for what?” Theo asked.

“Yes, exactly. We need time. We don’t have it yet, but we must get it. Do you understand?”

“Really, really no,” Alexander said. Wil wasn’t even listening, but Theo looked as confused as Alexander felt.

“Find what was lost,” Aunt Saffronia said, and there was something strange about her voice--it went from sounding sort of like an echo, to sounding like a rumble of thunder. Theo and Alexander felt it. They both nodded without quite knowing why.

“Very good. I’ll pick you up when it gets dark,” Aunt Saffronia said, her eyes fixed on a point far above their heads. “Outside, I mean. It might get dark in many ways far before then, but you are good, brave children.” She drove away without another word.

“Fantastic,” Wil said, not looking up from Rodrigo. “A week at a water park. If our aunt wasn’t going to bother watching us, why didn’t Mom and Dad just let me be in charge?”

“I’m gonna walk into traffic now,” Theo said, testing her.

“Hey, Theo,” Alexander said. “Do you think this knife is sharp enough? Here, hold out your hand.”

Wil had not heard a word, thus proving why, exactly, their parents did not leave her in charge. Perhaps if Theo and Alexander had texted Wil that they were going to get matching tattoos or were ingesting poisons in small doses to increase their tolerance, she might have responded.

But probably not.

“Why do you think they left us with Aunt Saffronia?” Alexander asked. “And do any of you remember her ever being mentioned? Wil, have you met her before?”

Wil just grunted noncommittally. “I’m busy,” she said, fingers tapping.

“I don’t really listen when Dad talks about his family, and Mom never talks about hers.” Theo shrugged.

“Doesn’t that seem weird? That Mom never, ever talks about her family, but suddenly we’re with a Sinister aunt? Is she Mom’s sister? Married to one of Mom’s brothers or sisters? Does Mom even have any brothers or sisters? And doesn’t Aunt Saffronia seem . . . ?”

“Too old?” Theo suggested.

But that wasn’t it. She didn’t look old, like as in wrinkly and decrepit. She looked old like a photograph you find in a box, youth captured but frozen and faded, long gone even though it’s right in front of you. Alexander opened his mouth to share that thought, but Theo had already moved on. She liked movement and hated standing still.

“So, the water park,” Theo said, hands on her hips as she slowly turned in a circle. “Where exactly is it?”

Aunt Saffronia had dropped them on the side of the road. The trees were old, green and gray, heavy with trailing Spanish moss. A few steps into their shade lowered the temperature by several degrees. The only thing they could see was a gravel road leading into the forest.

Alexander rubbed his arms against the sudden chill. “Maybe along this road?”

Theo went confidently in that direction, followed by Alexander and less quickly by Wil, who navigated much like a bat with echolocation, only without the echolocation. She stumbled on the occasional root and walked directly into at least one tree, neither action peeling her eyes away from her phone.

Theo ran her hand through her hair, making it stick up wildly. She had been trying for low-maintenance, and ended up looking a bit like a young, brunette Albert Einstein. “It’s a sign,” she said.

Alexander thought she was being metaphorical, referring to their being lost in the woods as a sign that their entire summer was doomed, until he followed her gaze upward to an actual sign.

In rusting wrought-iron, curling and twisting more elaborately than the ivy trailing from it, a gate stood. Along the top in imposingly sharp letters was written:

FATHOMS OF FUN Waterpark

Wil’s eyes flicked up and then back down. “It has five stars on . . . Gulp. Not Yelp. Gulp. I’ve never heard of Gulp.” Unconcerned, she continued walking forward, missing the edge of the gate by a hair.

Alexander hiked his backpack up, tightening the straps. He didn’t like water parks, or parks in general, though he was fond of water. Still, the sign felt more ominous than exciting. And decidedly un-water-parkish.

Theo loved water parks, and parks in general, and she was also very fond of water. “Race you,” Theo said.

“Race yourself,” Alexander answered.

Theo obliged, as she always did. She took off sprinting along the gravel road, pumping her legs and arms in perfect unison. She was very good at running, and climbing, and swimming. She was rather bad at sitting still, waiting, and spelling. Unlike Wil and Alexander, she was excited by the prospect of a week at a water park. With a full week, she could do all sorts of things. Time herself going down slides and aim for new personal records, adjusting for friction, body positioning, even the time of day. Make a course out of the slides and race Alexander to see who could get through fastest. And have a churro-eating contest. Last summer she’d been introduced to those delightful lengths of fried-dough-cinnamon-sugar goodness, and they tasted like happiness, like what summer vacation felt like. She was confident she would win any churro-eating contests. And it could impact her slide times in interesting ways!

All her thoughts of churro consumption came to a screeching halt as her sneakers slid on the gravel and she stopped just short of the entrance gates.

Wil and Alexander caught up. Wil kept walking. Alexander stopped next to his twin and stared.

Water parks are this:

The scents of chlorine, sunscreen, and water drying on pavement.

Sun-drenched bright colors--yellow and blue mostly, some red. Palm trees, real or fake. Rainbow-colored shade umbrellas. Aqua slides like twisty straws for giants.

Children running and laughing and screaming and crying, parents likely doing the same minus the laughing, everyone in tropical-print suits, board shorts, bikinis, wraps.

Somehow, Fathoms of Fun had entirely missed the meeting where water parks were explained. Theo and Alexander would have been sure it wasn’t a water park at all, except for the sign--carved in the base of a giant angel statue, the wings thrown forward to hide the angel’s face--listing prices for entrance, including suit and towel rentals. The prices were all listed in roman numerals.

“Whoa,” Theo said. “Do we have XVII dollars?”

“Yes,” Alexander said. “But do we want to have it, if it means we’re going inside there?”

Beyond the massive ivy-choked stone wall, beyond the wrought-iron gate slowly swinging open as if beckoning them in, was a tower. The tower loomed above the overhanging green trees, scraping against the sky itself. Rather than wood scaffolding, or even metal or plastic, the tower was made of the same heavy, weather-pocked gray stone of the wall. At various points along the tower, huge gargoyle heads leered, and between their jaws, gray slides extended like lolling tongues, twisting and looping away. At the very top of the tower, where one half expected either a lighthouse light or a cannon, there was a window. Theo frowned, thinking she saw a flash of white there, a hand pressed against the glass. But it was too far away to be sure.