1

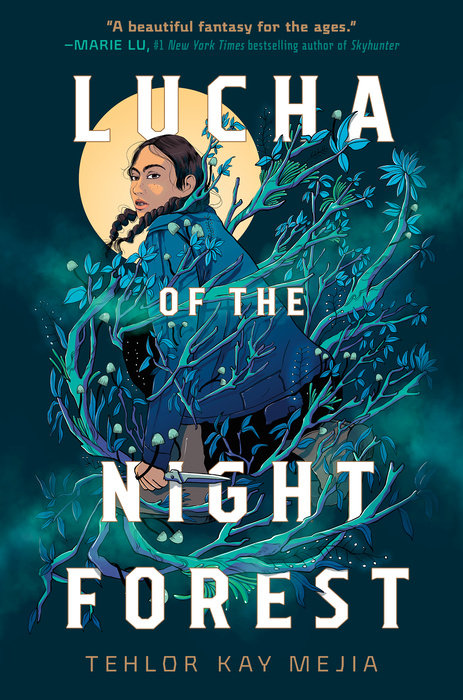

Robado was a night place, and tonight Lucha Moya was glad of it. In night places, no one looked twice at a girl like her. Even one with a long knife strapped to her belt.

In the south ward, at the very tip of the city, the streets were already filling with workers ready to celebrate the end of a grueling day.

Revelry wasn’t Lucha’s purpose tonight, but the crowd served her needs nonetheless. She slipped in among the bodies, moving north, trusting that her expression would deter conversation if her knife didn’t. She had no friends to worry about offending. None in the south ward, and none in this entire cursed city.

But no one came to the Scar—named for its utterly barren land—to make friends. In fact, no one came here at all. You were born here, you died here, and you lamented your rotten luck every day in between.

Lucha lamented her own as she fought her way out of the neighborhood she called home. The long, windowless manufacturing buildings with dilapidated worker housing crowded in…

1

Robado was a night place, and tonight Lucha Moya was glad of it. In night places, no one looked twice at a girl like her. Even one with a long knife strapped to her belt.

In the south ward, at the very tip of the city, the streets were already filling with workers ready to celebrate the end of a grueling day.

Revelry wasn’t Lucha’s purpose tonight, but the crowd served her needs nonetheless. She slipped in among the bodies, moving north, trusting that her expression would deter conversation if her knife didn’t. She had no friends to worry about offending. None in the south ward, and none in this entire cursed city.

But no one came to the Scar—named for its utterly barren land—to make friends. In fact, no one came here at all. You were born here, you died here, and you lamented your rotten luck every day in between.

Lucha lamented her own as she fought her way out of the neighborhood she called home. The long, windowless manufacturing buildings with dilapidated worker housing crowded in alongside them. The narrow tail of land pushing right up to the bank of the blighted salt river.

Too many bodies, Lucha thought. Not enough space to breathe. But that was how it had always been. If you wanted air, you had to pay for it. And the price was too high for most.

She stayed to the center of the road despite the crush, avoiding the river. She’d always been repelled by its expanse of murky nothingness. The salt that leached into the soil and killed everything living for a mile in any direction. The tang of it tainted the air, too. It warped the pressed wood-pulp walls of every structure, making gaps for the dark humors of the forest to steal in . . .

Enough, Lucha chastised herself. Plenty of monsters you can see in this world, no sense worrying about the ones you have to imagine.

Lucha knew the monsters of Robado as well as anyone—she’d lived here as far back as her memory stretched. In a larger unit with windows until she was nine. That hadn’t been quite as bad. But then her father had died, and everything had changed: their household income cut by half, her mother growing less and less reliable in her grief. They climbed down the housing ladder one rung at a time. Ever closer to the river. Beginning again, and again, and again . . .

But none of the units or sectors of the south ward Lucha had lived in had been remarkable. There was only one remarkable thing about Robado, and it came into view as Lucha turned onto the stone-paved road heading north.

The Bosque de la Noche was nothing but a massive, dark shape on any map she’d ever seen. The southern border was always defined by the curve of the river penning it in. But the forest itself extended to the northern edge of the page, staining it with solid ink, giving the impression the mapmaker’s brush had simply gone on until it could go no farther.

No one knew what was on the other side—or if there even was one.

Lucha’s steps slowed without her permission, her eyes drawn as always to the trees. Everyone else in this place seemed to avoid looking at the forest. Its seemingly sentient presence. But Lucha had never grown out of her childhood fixation with the wall of greenery that was their constant companion.

The forest was said to be uninhabitable. The governors of the Elegidan continent—skittish as squirrels and twice as greedy—refused to recognize any territory north of the river. They took their shares of Robado’s ill-gotten profits readily enough, but they claimed no authority in the city. Or any of the responsibility that would go with it.

The mapmakers, for their part, blotted the wood into their landscapes without sparing a stroke for this wound of a place clinging to its edge.

Like we don’t even exist, Lucha thought, still loitering in the middle of the road.

“Watch it!” snarled a man heading south. Lucha staggered backward, reminded of the dangers of standing idle. The little cart the man pulled turned sharply and splattered her shoes with mud.

She was about to shout something rude when she saw the cart’s tiny passenger. A girl of no more than four. She dangled her bare feet over the edge as her father rolled her along.

Lucha smiled, remembering her younger sister, Lis, at that age. Her huge brown eyes and shining curls . . .

“Better watch out!” the girl called in her lisping baby voice. “El Sediento will get you if you look too long!” Sticking her fingers into the corners of her mouth, the girl stretched her smile too wide and rolled her eyes back so only the whites showed.

The cart rolled on. From the direction of the night greenhouses drifted a song in a language she did not know. Lucha turned her boots north again. Along with the crowd of greenhouse workers, she moved into the city’s center as twilight gathered above the treetops.

It was here that the bodies around her became an impediment. The stream pooled at the Plaza de Centro like the huge marketplace was dammed. Greasy animal-fat lanterns flared to life as Lucha fought against the workers already queueing up to buy. Her pulse picked up speed.

The stall counters were lined with food and drink. Jars of cloudy cider made from a berry that was poisonous until fermented, carved wooden boats filled with chunks of meat in the same oil that made the lamps burn.

Other stalls sold handmade wares to tempt the superstitious. Stone talismans for protection, bundles of herbs for luck or love or money, tiny candles in every color said to ward off this or attract that. At one booth, an old woman sat silent in a black veil. In front of her were tiny painted portraits, their eyes drawing Lucha’s gaze.

The pale, angular face of a man, eyes black as the night itself. In his hands, a clay cup of blood. El Sediento, Lucha thought with a thrill. They’d all been warned as children not to linger too long in the trees for fear that he’d steal their souls—and even skeptical Lucha, so consumed with the practical details of her family’s survival, had seen him in her nightmares more than once.

She averted her gaze out of instinct. It landed on the next portrait instead, a woman this time. A goddess. Her face was round and shining. Her hair streamed all around her. Her eyes were somehow penetrating, even in this diminutive size.

The contrast was clear. Good and evil. Shadow and light.

Lucha turned away from this one, too. The old woman behind the counter was tempting fate even displaying it. Talk of this goddess, or any other, was forbidden in Robado.

The crowd grew livelier as Lucha reentered it, and she more desperate to be free of it. Not a single proprietor named their true product. They didn’t have to. The legitimate goods were just for show. It was what was under the counters that sold—passed from closed fist to shaking fingers. Paid for with teetering stacks of rusty coins, or else desperate promises that they’d pay tomorrow. Tomorrow . . .

Olvida. The forgetting drug.

In the Bosque de la Noche, and nowhere else on the continent, grew a short, scrubby bush, with silvery leaves that seemed to catch even the dimmest light. The Pensa plant. So named by the roaming witches and wise men who had once chewed it, it had been part of religious rituals before Robado had even existed. The leaves produced a mild, sleepy euphoria. They enhanced the voices of the spirits with whom the users communed.

If only people had left well enough alone, Lucha often thought. If only no one had ever discovered that, smashed to a pulp, its potent juice wrung out and heavily processed, the Pensa plant became infinitely more powerful. No longer used to gently open the mind to greater currents of inspiration. Instead, to obliterate it.

And so the greenhouses of Robado had been built to grow a domesticated version of the Pensa plant, and the manufacturing buildings to process it. The purified result was a powdered substance called Olvida—which produced a powerful forgetting effect. For a time, it would steal your cares, your worries, your memories. An effect in high demand in a city like this, where every day was a long, dangerous trudge toward sleep.

Olvida was the lifeblood of Robado—and the rotting death creeping through it.

“Forget for a night?” asked a hooded man at a stall without a line as Lucha passed. “All your worries gone, little sister. Your dreams at your fingertips.”

Lucha knew she should keep her eyes forward, but there was something about the way he said it. Little sister. It snapped in her like a dry twig begging for a flame. As if Lucha weren’t out here tonight because of her own little sister, left hungry by the drug in the man’s pockets.

She stepped up to the stall, anger kindling in her chest. The acid emptiness in her stomach only fed it. “You’re lucky I have somewhere to be,” she said, pulling her knife before she could think better of it. “If I didn’t, I’d slit your throat.”

Instead of cowering, the man only smiled. The row of teeth he exposed was rotten. “You’ll be back, little sister,” he said. “They always come back.”

“I won’t,” Lucha spat. “Not ever.”

“She’s holding up the line!” said a high, thin voice from behind her. “Out of the way!”

Several more voices joined in, a queue building behind Lucha as she stood with her knife exposed. Her cheeks flushed with a fury that died when she turned to look at them.

Lucha wanted to kill this man. To kill every bastard who sold Olvida in this marketplace. In Robado. In all of Elegido. Instead, she sheathed the knife and pushed through the crowd of faces with their haunted eyes, trying not to look for her mother’s.

The north ward was deserted by the time Lucha reached it.

All the rest of Robado was built on the salted ground, safe from the forest’s rampant growth. But Los Ricos, the self-appointed rulers of this lawless city, had grown greedy, and thus the north ward had come to be the kings’ seat of power. Carved into the center of what had once been an ancient woodland.