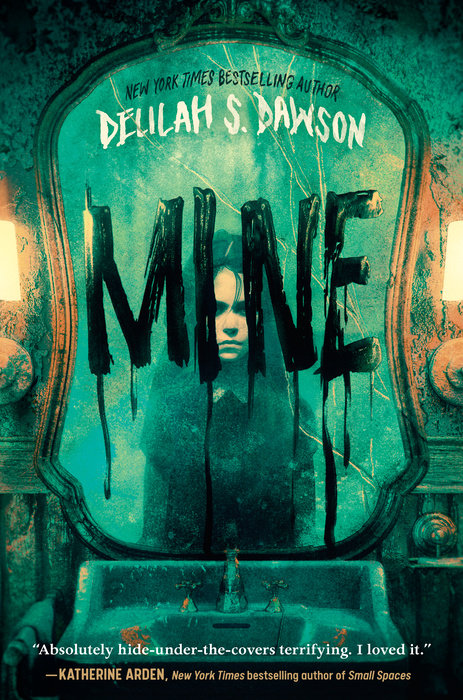

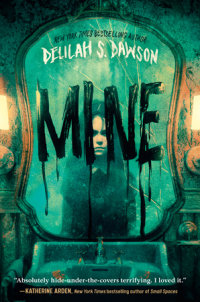

Mine

Author Delilah S. Dawson

Mine

A twisty, terrifying ghost story about twelve-year-old Lily, her creepy new home in Florida, and the territorial ghost of the young girl who lived there before her.

Lily's new house is a real nightmare. . . .

Lily Horne is a drama queen. It's helped her rise to stardom in the school play, but it's also landed her in trouble. Her parents warn her that Florida has to be different. It's a fresh start. No theatrics. But this time, the drama is coming for her.

The Hornes' new house is awful. The pool is full of slime, the dock is rotten, and the swamp creeps closer every day. But worst of all, the house isn't empty . . . it's packed full of trash, memories, and, Lily begins to fear, the ghost of the girl who lived there before her.

And whatever is waiting in the shadows wants to come out to play.

An Excerpt fromMine

1.

Lily Horne was dying.

Literally dying.

Okay, maybe not literally.

But very, very theatrically.

“This is the end!” she gasped, swooning as much as her seat belt would allow. “World . . . going dark. Can’t breathe . . .”

She took a moment to try out various moaning and gagging sounds, making sure she had the absolute attention of her audience, before naturally pivoting into the dramatic death that always made her cry.

“I was aiming for the sky,” she sang, low and questioning, following it up with a sputter.

“Oh God, no more Hamilton,” her mom moaned.

With a final gasp, Lily went rigid, eyes flown wide in shock and terror, then exhaled and let her bones melt so that her body went limp and unnaturally twisted, held up only by the constricting seat belt. Waiting for a reaction, she kept her breaths completely silent, her chest barely moving--a trick she’d learned from a video by a corpse actor on YouTube--a guy who actually got paid to pretend to be dead. A…

1.

Lily Horne was dying.

Literally dying.

Okay, maybe not literally.

But very, very theatrically.

“This is the end!” she gasped, swooning as much as her seat belt would allow. “World . . . going dark. Can’t breathe . . .”

She took a moment to try out various moaning and gagging sounds, making sure she had the absolute attention of her audience, before naturally pivoting into the dramatic death that always made her cry.

“I was aiming for the sky,” she sang, low and questioning, following it up with a sputter.

“Oh God, no more Hamilton,” her mom moaned.

With a final gasp, Lily went rigid, eyes flown wide in shock and terror, then exhaled and let her bones melt so that her body went limp and unnaturally twisted, held up only by the constricting seat belt. Waiting for a reaction, she kept her breaths completely silent, her chest barely moving--a trick she’d learned from a video by a corpse actor on YouTube--a guy who actually got paid to pretend to be dead. A little morbid, maybe, but it helped her land the part of Juliet last summer--and gave her a new possible career goal.

“You’re fine,” her dad said, pretending to be cheerful despite the fact that he was talking with his teeth clenched together. He glanced at her mom, who was quietly crocheting in the passenger seat, her head studiously down as she tried to avoid having this argument. Again. “Right, Laura?”

Mom looked up. “It’s going to be great,” she recited woodenly. “A new beginning.”

When Dad sighed, it was understood that he was disappointed in everyone--in Lily for being Lily, and in her mom for putting her in that first preschool production of Peter Pan and awakening her overly dramatic nature.

Would they respond this way, she wondered, if she were actually dying? Having a panic attack? Or a heart attack? If she just curled up and expired in the backseat without any of her telltale theatrics?

If so, they’d be sorry they hadn’t paid more attention.

As it was, she’d been sighing and flouncing and swooning and groaning around the house in obvious misery for weeks, ever since Dad had announced that they’d be moving to Florida. Lily didn’t want to move to Florida because it was an awful place and her new school probably wouldn’t have a drama club, or even a stage. Her Internet searches had revealed that there wasn’t a local theater in their new town.

She’d loved everything about Boulder, Colorado, from the audaciously wide skies and tall mountains to the startlingly sudden snowstorms and the fields full of popcorning prairie dogs. She’d especially loved their local playhouse--which was an actual Quonset hut, according to the many informational placards she’d read in the hallways over the years while in line to audition. She’d never wanted to leave--until she departed for New York or Hollywood. Now the deeper south they drove, leaving her entire world behind, the worse she felt. Colorado was full of bright surprises, but Florida seemed so old and withered. Everything here was too hot and shriveled to do anything but make swampy fart sounds.

Lily wouldn’t even let herself think about the reason they’d had to leave. Her dad kept insisting Florida was a chance to start over, so when she saw the blue Florida sign with the oranges on it, she closed her eyes and lifted her feet to jump into her new life. She felt it, the exact moment they crossed that invisible border. It was as if a barrier resisted her slightly, as if the hot summer sun rejected exactly who she was, or at least wanted to punish her for rejecting it first. When she put her feet down, she felt no victory.

The miles rolled by and the car inched along the cracked, lonely highway, deeper and deeper into central Florida, an adventurer crawling toward death in a desert while vultures circled overhead. Unlike the rush of stage jitters, this panic sat in her belly, heavy as a lump of cafeteria pizza that should’ve been good but was actually terrible.

“Just a few more miles,” Dad said, even though it was perfectly obvious, thanks to the map app on his phone in its stand on the dashboard.

The setting sun slashed viciously through the car windows, and Lily tried to shrink away, as her pale skin sunburned easily. But with the rest of the backseat packed so tightly with bags and boxes, there was nowhere to hide. She was stuck. All the things she wanted--comfort, choice, freedom, the ability to be her overly dramatic self--had been taken away.

The motion sickness medicine they’d given her every four hours had worn off, and her cell phone was almost out of battery. She couldn’t even text her best friend, CJ, back in Colorado. The only thing she wanted more than for the car to stop was for Dad to just turn the old sedan around and head straight back to their empty house, the house where she’d grown up, where she knew and loved every brick, and where she’d arranged her big, walk-in closet into a stage. But she knew better than to say that out loud. Every time she brought up Colorado, her dad’s face went red, and his mouth pinched down, and he looked away. She couldn’t remember the last time he’d genuinely smiled at her.

“Are you excited back there?” he asked with the forced cheerfulness of a mall Santa. He’d been that way ever since he’d accepted the new job in Tampa, as if saying that this was a good move for the family a hundred times a day could make it true. His acting skills were extremely subpar.

“No. I told you: I’m dying,” Lily answered. “My heart--”

“You’re not dying. You’ve got to stop being so melodramatic. We talked about this.”

But . . . Lily’s entire life revolved around being dramatic, and . . . well, the panic wasn’t too far from the truth. She was out of Colorado for the first time ever, destined to die of an exploded heart in the state that--to her--only existed because of Disney World. She didn’t know anyone here, her parents were always angry at each other, her dad was always annoyed with her, and she had an entire summer to sit around, worrying about what would happen when she started eighth grade at a school that probably had no drama club and no fall musical.

And although she’d asked to see pictures of the new house, her parents had only shown her one--of the outside. Which meant there was something wrong with it. Her room was probably super tiny and didn’t have a closet.

Finally they turned off the highway, cruising past palm trees and plants that looked like giant pineapples.

“This is Land O’ Lakes,” her mom said--the first thing she’d spontaneously offered in hours. She couldn’t even pretend to sound excited. “Our new home.”

They passed stores and chain restaurants and, surprisingly, cows. The sun began to set, fiery orange and pink against a sky gone the soft purple of milk left in a bowl after eating marshmallow cereal. The streetlights came on as the car entered a residential area, and Lily noticed that most of the homes here hid behind high wrought-iron fences and heavy stone walls, like medieval citadels constantly under fire. Beyond the black bars, she sometimes caught a glimpse of kids riding bikes or swimming in pools surrounded by weird cages made out of screens.

But her dad didn’t turn the car into any of these comfortable, walled-off communities. He put on his blinker and slowed to turn down a mangy dirt road flanked by sharp bushes nestled in sand. Scrubby forest hid what lay beyond, and the headlights flashed over low branches dripping with grotesque gray moss that looked like witch hair.

“Don’t touch that stuff,” her mom said. “It’s full of lice.”

“Mites,” Lily corrected. She’d Googled all the ways to die in Florida so that she’d be prepared.

Mom’s voice quavered like she was going to cry. “Just don’t touch it.”

Up ahead, a shape appeared amid the trees, and Lily recognized the building she’d seen in that one picture on Dad’s phone. The house was brown and angular and strange, with sloping roofs and big windows--it almost looked like it was half buried underground. Just in front of it, a bright blue dumpster sat, the only hard, colorful object in a sea of rustling shadows.

But the house didn’t quite match that picture she’d seen, either. It looked . . . sadder. The gutters were stuffed with leaves and the sprouts of baby trees, the fence was falling down, weeds were growing knee-high, and an old recliner sat out front with stuffing exploding out of squirrel-chewed holes. The car rolled to a halt, and Lily realized that the house didn’t look like it was all shined up for sale--it looked like it had been abandoned years ago.

“What’s wrong with it?” she asked.

Her mom sighed, and her dad quietly but firmly said, “It just needs a little TLC.”

“Tender loving care,” her mom said, glancing at Lily’s confused face. “It was a bank sale. We have to clean it out.”

“Hence the dumpster,” Lily finished with great gravitas. “We bought a dumpster house.”

Dad ignored that and got out first, leaving the headlights on and his door open. Mom sniffled as if sucking down a sob, picked up her purse and yarn bag, and got out, too. When Lily didn’t budge, her dad opened the back door for her and said tightly, “Stop this moody nonsense and get out of the car. It’s not that bad. You just always have to make everything into such a big production.”

Lily flinched. He always talked to her now as if she did everything specifically to annoy him. He used to smile at her, eyes twinkling, like he didn’t quite understand her but was still fond of her. But not anymore, not after the night last winter when . . .

Nope. Lily wouldn’t let herself think about it.

She raised her chin, undid her seat belt, and scanned the darkness out beyond the house, where tall trees and pointy-leaved bushes crowded close, their shadows shifting restlessly beyond reach of the car’s headlights. Two green sparks flashed and disappeared into the brush.

Eyes.

Lily had read that the animals in Florida were somehow wilder than elsewhere, like they hadn’t changed much since the time of the dinosaurs. Burmese pythons and other big snakes bred in the wild here and terrorized the swamps, and the trees were drooping with big cats and murderous birds. She wondered what kind of strange creature lived out there, one foot on her property and the other in the wilderness.

She stepped out of the car. The heat settled on her like a wet, suffocating blanket, and a drop of sweat trickled down her face. Her long dark hair felt heavy on her neck. Thunder rumbled threateningly, shaking the ground, and the sounds of the night bore down on her, a chorus of hums and peeps and screeches unlike anything she’d ever known in Colorado. It sounded like a pet store. She couldn’t see a single neighboring house from here, and yet somehow this place felt too hot, too crowded, too heavy, too loud, pressing in on all sides. When she looked at the building before her, an odd numbness crept down her arms. It just felt . . . wrong. Every instinct urged her to unleash a stage scream, the kind that would rattle down her throat and make adults finally take notice.

But she didn’t, in part because she didn’t want to give those green eyes any indication that she was a frightened prey animal, and in part because her dad was already mad and, like the night, just looking for a reason to boil over.

Lily had the distinct feeling the house was going to open its mouth and swallow her whole. She felt tiny and helpless, and she hated that. The fear turned to bubbling anger--at her parents for bringing her here, at herself for what she’d done to start this chain of events, and at Florida for being . . . Florida. She threw herself back into the car, slamming the door shut and crossing her arms.

“I wish I was dead,” she growled.

She didn’t really, not quite.

She just didn’t want to be here.