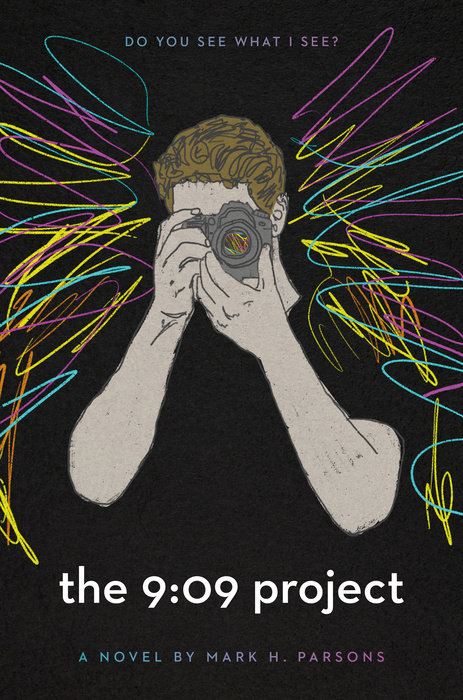

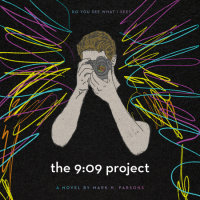

The 9:09 Project

Author Mark H. Parsons

The 9:09 Project

A thoughtful exploration about finding oneself, learning to hope after loss, and recognizing the role that family, friends, and even strangers can play in the healing process if you are open and willing to share your experience with others.

It has been two years since his mom’s death, and Jamison, his dad, and his younger sister seem to be coping, but they’ve been dealing with their loss separately and in different ways. When Jamison almost forgets…

A thoughtful exploration about finding oneself, learning to hope after loss, and recognizing the role that family, friends, and even strangers can play in the healing process if you are open and willing to share your experience with others.

It has been two years since his mom’s death, and Jamison, his dad, and his younger sister seem to be coping, but they’ve been dealing with their loss separately and in different ways. When Jamison almost forgets the date of his mother's birthday, he worries that his memory of her is slipping away. To help make sense of the passing of time, he picks up his camera—the Nikon his mother gave to him.

Jamison begins to take photos of ordinary people on the street, at the same time and place each night. As he focuses his lens on the random people who cross his path, Jamison begins to see the world in a deeper way. His endeavor turns into a school project, and then into something more. Along with his new outlook, Jamison forges new and unexpected friendships at school. But more importantly, he’s able to revive the memory of his mother, and to connect with his father and younger sister once again.

An Excerpt fromThe 9:09 Project

CHAPTER 1

It is not enough to photograph the obviously picturesque.

--Dorothea Lange

“Can stupidity make your head hurt?” Seth asked me.

“Only other people’s heads,” I said. “Never the stupid guy’s.”

He looked toward the other end of our table. “Well, that explains a lot.”

We were in the cafeteria, eating lunch while trying to ignore Beal Wilson and his buds and their rating game. Those geniuses had started a ten-point system at the beginning of the school year. Who knows why . . . maybe they saw it in a movie and missed the entire point? Now, a week in, they’d finalized it. According to them, any girl under a five was so far below grade she wasn’t even worthy of notice or discussion. (As a corollary to this, by doctrine they’d hook up with anyone five or above. So really, it was a binary go/no-go system, not a ten-pointer. But it was useless trying to tell them this. Trust me--besides being sexist asshats they aren’t exactly La Montaña High’s best and brightest.)

They continued with their hot-or-not bullshit while I looked for…

CHAPTER 1

It is not enough to photograph the obviously picturesque.

--Dorothea Lange

“Can stupidity make your head hurt?” Seth asked me.

“Only other people’s heads,” I said. “Never the stupid guy’s.”

He looked toward the other end of our table. “Well, that explains a lot.”

We were in the cafeteria, eating lunch while trying to ignore Beal Wilson and his buds and their rating game. Those geniuses had started a ten-point system at the beginning of the school year. Who knows why . . . maybe they saw it in a movie and missed the entire point? Now, a week in, they’d finalized it. According to them, any girl under a five was so far below grade she wasn’t even worthy of notice or discussion. (As a corollary to this, by doctrine they’d hook up with anyone five or above. So really, it was a binary go/no-go system, not a ten-pointer. But it was useless trying to tell them this. Trust me--besides being sexist asshats they aren’t exactly La Montaña High’s best and brightest.)

They continued with their hot-or-not bullshit while I looked for the chance to practice my street photography skills. Given the choice I’d rather use my Nikon but there’s no way I’m dragging it around all day in my backpack, so I’m not above using my phone.

I’d just snapped someone walking toward the exit with a tray in her hand. I hadn’t seen her before, but something about her walk caught my eye. Like she meant business. Okay, and maybe something else. Just before I hit the button I reframed it so she was leaving the frame instead of entering it, and panned with her so she was sharp and the background was blurry. Like she was almost too fast to catch. After I snapped it, I took a quick peek at it. Yeah, that works. Underneath it all I could still hear Beal yakking away . . .

“. . . so, I’d say that’s a seven-five. Well, at least a solid seven.”

“Solid,” his buddy Tristan said with a snort, like the word was somehow funny.

I looked up. They were talking about the girl I’d just photographed. I never joined their rating games, but I couldn’t imagine thinking of her as “nice and ordinary,” or whatever they thought a seven was supposed to be.

“You’d better not let her hear that,” Riley said. “They call her AK-47 for a reason.” Riley is Beal’s other sidekick.

“So?” Beal said. “There’s nothing wrong with that. I’m just saying she’s fine. She’d rate even higher if she wasn’t so damn scary.” He looked down toward our end of the table. “Right, Seth?”

“You’re clearly the expert, dude,” Seth said.

Beal nodded, missing the irony. “J? What do you think?”

“Hmm. I think . . .” I paused, considering my impression of the girl. Leave it to my weird brain to come up with a cartoon image of a tour guide leading people through dangerous territory. “I think if I suddenly had to survive in an undisclosed jungle location in Argentina and could take just one student from this cafeteria, I’d choose her.” They stared at me. “She has a little Che Guevara in her,” I added for clarification.

Beal shook his head. “Man, you’re weird.”

With a few minutes left before the bell Riley suddenly came to life, all excited. “Dude, look at that! Is she new? Man, I’d be all over that. She’s an eight. At least. Maybe an eight and a half.”

“Eight and a half?” Seth replied, without looking up from his phone. “So, she’s not quite uber-hot, but still clearly hotter than just hot? Like, semi-uber-hot?” He paused his sarcasm long enough to glance up at the girl in question. He isn’t the type to make rude comments, but I could tell she had his attention.

Beal weighed in. “Eight-five, easy.” He paused for dramatic effect. “I’d let her give me a sleeper.”

“. . . says the guy who couldn’t get a labradoodle to lick his noodle even if he put peanut butter on his balls,” Seth muttered to me.

I turned my head for a look. It was Ollie. Of course. And she was coming this way. She’d started high school with a fashion-forward vengeance last week and apparently aimed to keep it that way. Today she was messy-blond-hair/surprised-eyes/preppy, like Taylor Swift’s little sister who’d been out too late the night before.

“She’s a freshman,” I said.

“That don’t plug no holes” was Beal’s brilliant retort.

“Wow--you make that up just now?” Seth asked.

They suddenly ran out of things to say as she approached our table and walked up to me. “So,” she said quietly. “Do you suppose I could get a ride from you after school?” You’d have to know her to realize the microscopic crinkles in the corners of her eyes meant she was smiling underneath the puppy-dog face. She knew what she was doing, and I knew it. And she knew I knew.

I paused, like I had to think about it. “Okay,” I finally said. “I’ll wait for you in the parking lot.”

She nodded. “Thanks.” She turned and walked away without ever making eye contact with any of the other guys.

Once she left, they all turned toward me with that What the hell? look. And never one for subtlety, Beal said, “What the hell, J? You’re all like Mister Quiet Loner all the time and it turns out you got a little hottie in your back pocket or what?”

I just shook my head, like You dumb bastards, then grabbed my backpack and stood up. “Like I said, she’s a freshman.” I headed out to my fifth-period class.

It’s not that I was trying to mislead them. I just wasn’t in the mood to deal with a pack of loser horndogs trying to get me to hook them up with my little sister.

History class. There are a few secrets to it, at least at La Montaña High School:

1. Know the important names and dates of the major events. (Subtle hint: these are the ones they tell you.)

2. Maybe also remember the barest facts about them if you’re really shooting for an A+.

3. Let the teacher know you know. Don’t hide in the back of the class. Don’t sit front and center--unless you’re an unrepentant kiss-ass--but second or third row, maybe one seat off center, will work fine. And engage, or what’s the point?

4. But don’t piss the teacher off. Okay, I’m not great with this one. Or even moderately good. Like the fact that Mr. LaRue was born without a sense of humor is somehow my fault?

That’s it. Not much heavy lifting involved, just regurgitation.

Like today. I was gazing out the window at some hills in the distance, still thinking about those idiots in the cafeteria, when LaRue said, “Who can give me a military leader after the Civil War who rose to political prominence?” He looked at his seating chart--for the biggest offender, apparently--and said, “Jamison Deever?”

I swung my head around. “Huh?”

“Civil War. Military leader. Rose to prominence after.” He literally snapped his fingers, like I was a trained seal or something. “Weren’t you paying attention?”

The moment he said Civil War a timeline popped up in front of my eyes--the latter half of the nineteenth century. The timeline scanned to the Civil War era--early 1860s. It was blue. Which makes no sense, as you’d think a war should be red due to blood and violence, but it had more to do with the fact that the letter C is definitely light blue. A famous name from the war still stuck out after the war was over. Ulysses S. Grant.

The phrase 8+8 hovered in front of my eyes. In light gray, of course, as eights are. I knew the Civil War started in 1861 (see Secret #1, as previously stated), and the phrase reminded me that Grant became president eight years afterward, for eight years. “Grant. He became president of the US in 1869 and served two terms, until 1877.”

LaRue studied me for a moment. “That’s correct. But I suggest you keep your attention within the room from now on.” He turned away. “Now, who can tell me about the reconstruction effort during . . .”

Okay, there’s another secret. Maybe.

5. Have the neurological condition known as synesthesia.

It’s not contagious. Or fatal. Or even harmful. In fact, if there were a cure, I wouldn’t take it--life would seem too bland. And my grades would probably take a dive.

For as long as I can remember, certain things--like letters, numbers, days of the week, months of the year--have had definite colors. And those colors don’t change. Like, A is sort of a pastel orange, like orange sherbet mixed with vanilla ice cream. Always. Just like 7 is always a thin sort of purple, and Wednesday is a broad, boring, light brown/tan. Just like the day itself feels. And when someone says “Wednesday,” I instantly see it in a little box, with Monday and Tuesday in their own boxes to the left of it (in gray and yellow, respectively), and Thursday and Friday to the right (blue and brown . . . duh). It might sound goofy, but I have no control over it.

There are other manifestations. Like when someone talks (especially droning on in a boring way, like a certain US history teacher I know), I see the words spooling by as they speak, spelled out in bold, black letters like the captions at the bottom of a newsfeed. And sometimes I see ideas played out as strange little cartoons, like my brain was an anime studio on drugs or something.

My mom said most of this was the same for her. I can remember sitting with her at the kitchen table when I was a little kid, comparing notes. Like, “What color is Tuesday to you?” And she’d say Green, and I’d say “No way! It’s totally yellow. What about November . . . ?”

I never gave it much thought--I guess I’d assumed it was pretty universal. When I learned otherwise, I’ve got to tell you, I was kind of stunned. I was helping my dad in the garage where he had an NPR science program on the radio and they were talking about how some people had this condition where they associated colors with letters or numbers, or sometimes with sounds or other cross-sensory stuff. I remember thinking This is news? but then they said it was a neurological condition called synesthesia, and apparently it only affects a small percentage of the population. I’ll admit for a second there I was a little worried because it sounded like some sort of disease--somewhere between amnesia and diarrhea. But then they said there were no known negative side effects, blah blah blah . . . possible correlations with creativity or memory . . .

But all I could think was, you mean everyone doesn’t do this? Seriously, it’d be like seeing the headline, Scientists report some people can breathe through their nose!

“I’d kind of figured most people saw things that way,” I said to my mom, “but I guess not. Apparently, it’s pretty rare.”

She looked at me with the same little crinkle in her eyes that Ollie’d had today and nodded. “I knew that. I never made a big deal out of it because I didn’t want you to feel ‘different.’ But you have to admit it’s pretty cool, don’t you think?”

Yes, I did. But now that feeling was gone--along with my mom--and no one else seemed to have her ability to understand me or help me feel less alone in the universe.

As for my sister, sure enough she was waiting in the parking lot, leaning against Mom’s old Subaru Outback. Yeah, it still kind of weirded me out, driving it. But it beats walking. I guess.

As I unlocked the car, one of the seniors rolled by in a new Camaro. What my dad called a Faux-maro. Bright yellow. We both watched it, appraising the potential perfection of this particular hue.

“Perfect?” Ollie asked.

I shook my head. “It’s a couple shades too dark.”

Ollie shot me a look. “It’s always something with you, isn’t it?”

CHAPTER 2

Photographers stop photographing a subject too soon, before they have exhausted the possibilities.

--Dorothea Lange

As soon as I rolled out of the parking lot Ollie had her face in her phone. I figured she was texting, like always. But when we stopped at a red light, she held it up and showed me a pic of a model. She was Latina, professional-grade hot. Wild dark hair, with some sort of smoky thing going on around her eyes. Just this side of a raccoon. But a really attractive raccoon.

“Judge,” she said. Probably because I tell her Don’t be so judgy at least three times a week. “Which do you like better? This one, or”--she scrolled to another pic--“this one?” If the first one was “sultry,” the second was at the other end of the continuum, over toward “fresh-faced” or whatever. A white girl--beachy-blond, blue eyes, big smile. Also, professionally hot.

“So, am I judging the pro hair and makeup, the studio lighting, the fan-in-the-face, or the Photoshop skills?”

She took her phone away and pulled a face. “Can’t you be serious for once?”

“I am. No one looks like that in real life.”

“Well, duh. But if they did, which one would look better?”

I was about to render a preference, then stopped. Did I really want to come off like Beal? “They both look great.” And regardless, they were both way out of my league.

“J!”

“Okay. Maybe the first one? Something about the look in her eyes . . . she seems smart.”

She leaned back in her seat and folded her arms, looking away. “You’re useless.”

I glanced over at her. “This is for you, right?” She was still looking forward, but her head bobbed almost imperceptibly. “Look. You’re my sister, so to me you’re not even like a real girl.” She started to say something, but I kept going. “However, some of the guys at school seem to like the way you look--God knows why--so maybe you should consider just sticking with whatever you’re doing now. If it even matters to you, I mean.”

I was expecting her usual pushback, like Fashion is an art form and It’s not about hotness, but instead she said, “They do?”

I had her full attention now, so I told her all about their messed-up rating system.

“What did I get?” she asked.

“Seriously? You care what Beal Wilson--who’s grown into an all-around snarky dickwad--gave you on his patented hotness scale?”

“No. I was just curious. But if you don’t want to--”

“Eight.”

Her eyes narrowed. “So that’s it? I’m eighty percent? Like a B or something?” This from a girl who cares about her grades almost as much as her fashion. Not quite, but it’s close.