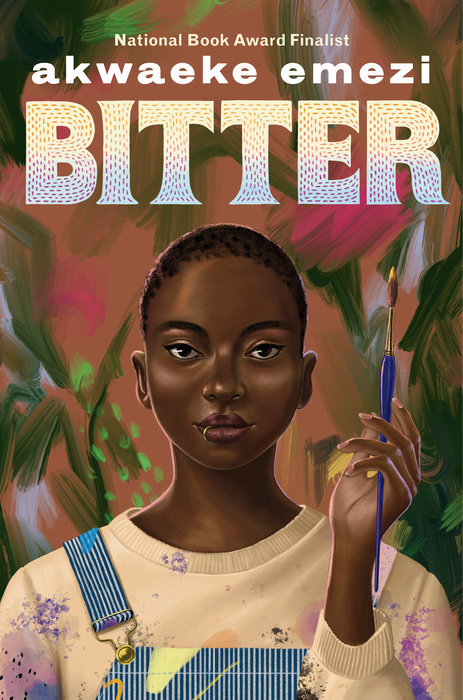

Bitter

Author Akwaeke Emezi

Bitter

From National Book Award finalist Akwaeke Emezi comes a companion novel to PET that explores both the importance and cost of social revolution--and how youth lead the way.

Bitter is an aspiring artist who has been invited to cultivate her talents at a special school in the town of Lucille. Surrounded by other creative teens, she can focus on her painting--though she hides a secret from everyone around her. Meanwhile, the streets of Lucille…

From National Book Award finalist Akwaeke Emezi comes a companion novel to PET that explores both the importance and cost of social revolution--and how youth lead the way.

Bitter is an aspiring artist who has been invited to cultivate her talents at a special school in the town of Lucille. Surrounded by other creative teens, she can focus on her painting--though she hides a secret from everyone around her. Meanwhile, the streets of Lucille are filled with social unrest. This is Lucille before the Revolution. A place of darkness and injustice. A place where a few ruling elites control the fates of the many.

The young people of Lucille know they deserve better--they aren't willing to settle for this world that the adults say is "just the way things are." They are protesting, leading a much-needed push for social change. But Bitter isn't sure where she belongs--in the art studio or in the streets. And if she does find a way to help the Revolution while being true to who she is, she must also ask: what are the costs?

Acclaimed novelist Akwaeke Emezi looks at the power of youth, protest, and art in this timely and provocative novel, a companion to National Book Award Finalist Pet.

Praise for PET:

"The word hype was invented to describe books like this." --Refinery29

NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FINALIST

"[A] beautiful, genre-expanding debut. . . . Pet is a nesting doll of creative possibilities." --The New York Times

"Like [Madeleine] L'Engle, Akwaeke Emezi asks questions of good and evil and agency, all wrapped up in the terrifying and glorious spectacle of fantastical theology." --NPR

An Excerpt fromBitter

Chapter 1

Bitter had no interest in the revolution.

She was seventeen, and she thought it was ridiculous that adults wanted young people to be the ones saving the world, as if her generation was the one that had broken everything in the first place. It wasn’t her business. She was supposed to have had a childhood, a whole world waiting for her when she grew up, but instead kids her age were the ones on the front lines, the ones turned into martyrs and symbols that the adults praised publicly but never listened to because their greed was always louder and it was easier to perform solidarity than to actually do the things needed for change. It didn’t matter. None of it fucking mattered.

Bitter sat in her room and ignored the shouts from outside her window, the stomping of feet, the rhythmic chants, thousands of throats swelling to the same song. Lucille was a brutal city to live in. There had been mass shootings at the public schools, at the movie theaters, at the shopping centers.

Chapter 1

Bitter had no interest in the revolution.

She was seventeen, and she thought it was ridiculous that adults wanted young people to be the ones saving the world, as if her generation was the one that had broken everything in the first place. It wasn’t her business. She was supposed to have had a childhood, a whole world waiting for her when she grew up, but instead kids her age were the ones on the front lines, the ones turned into martyrs and symbols that the adults praised publicly but never listened to because their greed was always louder and it was easier to perform solidarity than to actually do the things needed for change. It didn’t matter. None of it fucking mattered.

Bitter sat in her room and ignored the shouts from outside her window, the stomping of feet, the rhythmic chants, thousands of throats swelling to the same song. Lucille was a brutal city to live in. There had been mass shootings at the public schools, at the movie theaters, at the shopping centers. Everyone knew someone else who had died from something they didn’t have to die from. Too many people had seen others die, even if it was in frantic livestreams and videos, witnesses risking their lives and freedoms to record the cops and their gleeful atrocities. Too many mothers had buried their children under a lethally indifferent administration. All of Bitter’s friends were sick of it, and rightfully so. The world was supposed to have gotten better, not become even more violent, rank with more death. It was no wonder the people took to the streets, masses swallowing the roads and sidewalks, because in a world that wanted you dead, you had to scream and fight for your aliveness.

Sometimes Bitter wished she didn’t live so close to the center of the city, though; every protest in Lucille seemed to stream past this building, the sound leaking up the walls, levering its way over her windowsill, stubbornly penetrating the glass and blinds and curtains. Bitter wished she could soundproof it all away. She curled up in the large gray armchair pushed against the wall as far from the window as her room would allow and bent her head over her sketchbook, turning up the old-school music in her headphones and worrying at the steel ring in her lower lip. The metal was cool against her tongue, and Big Freedia’s voice fell into her ears over an accelerating beat as Bitter mouthed the words along, trying to match the speed, her pencil making quick, strong strokes over the paper. A mouth grew under her hand, a tail and a sleek neck, smooth round scales packed neatly on top of each other, curve after curve peeking out. She made its eyes as dark as she could, small black stones nearly weighing through the paper.

Sometimes, when she had music filling her ears and paper spreading at her fingers, Bitter could almost feel the bubble she was building, as if it was tangible, a shield that would protect her better than her weak windows. If she got it just right, maybe she could block out everything else entirely. Maybe when the stomps and chants five floors down on the street turned into screams and people running, the bubble could block out the other sounds that Bitter knew would come with it—the clank and hiss of canisters, the attack dogs barking, the dull heaviness of water cannons spitting wet weight on flesh. On the bad days, there was gunfire, an inhuman staccato. Sometimes the streets were hosed off afterward. Bitter frowned and bent closer to her drawing, adding a crest of spikes. It looked like a dragon now, which was fine, but it just wasn’t right. She ripped out the sheet from her sketchbook and crumpled it into a messy ball, tossing it aside. She’d have to start again, pay more attention to what she was pulling out of the page.

Almost immediately, she felt a brief pang of regret at having crumpled up the dragon. Maybe she could’ve tried to work with it instead, but Bitter knew the answer even as she asked the question. There were things she could draw and then there were things she could draw, and when the streets were loud the way they were this evening, only the second sort of thing would do. Only the second sort of thing could make her feel a little less lonely.

She was about to start sketching again when her door swung open and someone stepped in. Bitter pulled off her headphones, pissed at the interruption, but the visitor raised her hands in peace. “Don’t even start, Bitter—I knocked! You never hear anything with those headphones on.” She was a tall girl in a neon-pink hijab that framed her soft face. Her lashes were a mile long and tiny iridescent stickers were scattered over her cheekbones. Bitter relaxed. “Hi, Blessing. Wha’s the scene?”

Without her headphones, the sounds from the street seemed to fill up her room. Blessing sat on the bed, stretching her legs out in front of her. Her jeans and hoodie were covered with colorful doodles, flowers and suns and rainbows. It was aggressively adorable, and Bitter hid a smile. The two girls had been friends for years, since they’d both come to this school and started living in the dorms, small bedrooms lined up next to each other. Blessing had been the one who shaved Bitter’s head for the first time, dark tufts of hair falling in clouds around them, and Bitter had kept her curls cropped close since then, because she could, because here she was as free as she’d ever been. They both knew how special that was. Blessing had been in and out of queer shelters since her parents kicked her out, but then a social worker found her and told her the same thing Bitter had been told—that there was a private boarding school called Eucalyptus, that it was for young artists and she’d been selected, that none of the students had to worry about paying for it. All they had to do was graduate.

It made no sense. No one knew who owned the school, only that it was full of kids like Bitter and Blessing who had been found and brought somewhere safe. They all had the same story of the first time they walked into Eucalyptus: the rush of relief and security they’d felt when they met Miss Virtue, the extraordinarily tall woman who ran the school. Miss Virtue had a deep voice, a shock of steel hair, and the most eerie gray eyes, and she was always dressed in the sharpest suits they’d ever seen, not to mention that she was the kindest person they’d ever met. All the kids ignored that first rush of relief because they’d learned the hard way that you couldn’t trust first impressions, but after a while, they also learned that Eucalyptus was different, and that was because of Miss Virtue. You couldn’t help but feel safe around her, not because she was soft or anything, but because there was something behind her dark skin, something terrifying that leaked through her gray eyes and made everyone uncomfortably aware that her kindness was a deliberate choice. It also made them feel safe, like she would go to horrific lengths to protect them, and that was what they needed, someone who believed they were worth burning the world down for.

Still, all the students were curious about who Miss Virtue worked for, whose money ran Eucalyptus, how and why they had been chosen to attend, but there were no answers for these questions. Even the hacker kids couldn’t find a trail that would explain any of it. Bitter didn’t care. Eucalyptus was safe, and that was all that mattered, especially when you knew what other options were out there. Bitter had bounced around foster homes since she was a baby, ending up with a steady foster family when she was eight, and she had removed all memories of the years before that, on purpose, because she needed to stay sane and some memories were like poison.

Her new foster family had known her biological parents, but they hadn’t liked Bitter very much. Your father was a monster, the woman there used to say, and you’re going to end up nowhere. It kill your mother, you know—that’s why she give you this name, that’s why she did die when you was a baby, you born with a curse. They were religious, and they didn’t like how loud Bitter was, how she stared at them with unflinching eyes, how she liked to draw almost as much as she liked to talk and challenge and yell. It was just Bitter and the woman and her husband, both from her mother’s island, both stern and cold, and while they weren’t as cruel to Bitter as she felt they could’ve been, her whole life in that house had been one continuous wilting. When she’d pierced her lip, the woman had slapped her so hard that new blood fell against Bitter’s teeth, so she’d started running away like she was taking small calm trips. Inevitably, she was found and brought back, found and brought back, until the Eucalyptus social worker found her and asked her if she wanted to leave, and yes, hell yes, she wanted to leave. And the woman and the man came and said goodbye and preached at her for a little bit, told her things about herself Bitter had stopped believing, and then the social worker took her away, and then there was Eucalyptus and Miss Virtue and Blessing, and Bitter had all the friends she could roll with, all the time to draw that she wanted, and a room with a door she could lock, even if it was all too close to the city center.