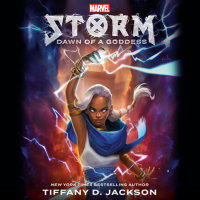

Storm: Dawn of a Goddess

Before she was the super hero Storm of Marvel's X-Men, she was Ororo of Cairo—a teenaged thief on the streets of Egypt, until her growing powers catch the eye of a villain who steals people's souls. An epic origin story that will blow you away, from the New York Times bestselling author of Monday's Not Coming.

The gorgeous first edition hardcover of Storm: Dawn of a Goddess will feature an electrifying dust jacket that glows in the dark!

"Tiffany D. Jackson has crafted the story of Storm that the world has been waiting for!" —Nicola Yoon, #1 New York Times bestselling author

Few can weather the storm.

As a thief on the streets of Cairo, Ororo Munroe is an expert at blending in—keeping her blue eyes low and her white hair beneath a scarf. Stealth is her specialty . . . especially since strange things happen when she loses control.

Lately, Ororo has been losing control more often, setting off sudden rainstorms and mysterious winds . . . and attracting dangerous attention. When she is forced to run from the Shadow King, a villain who steals people's souls, she has nowhere to turn to but herself. There is something inside her, calling her across Africa, and the hidden truth of her heritage is close enough to taste.

But as Ororo nears the secrets of her past, her powers grow stronger and the Shadow King veers closer and closer. Can she outrun the shadows that chase her? Or can she step into the spotlight and embrace the coming storm?

In her first speculative novel, New York Times bestselling author Tiffany D. Jackson casts a breathtaking spell with one of Marvel's most beloved characters, and brings the superhero Storm to life as you've never seen her before.

An Excerpt fromStorm: Dawn of a Goddess

One

Ororo Munroe stood on the steps of her primary school, little six-year-old fingers splayed, glancing up at the sky, willing the gates to open so she could escape.

A group of girls behind her giggled, whispering in Arabic. She wasn’t familiar with the language yet, but their voices echoed in her ear. Just that day, she had asked a teacher to translate a word she often heard thrown in her direction during recess, and it now made her want to vomit.

“White jungle monkey,” they taunted.

Back straight, eyes puffy from crying in the wash closet, she stared down the street, anxiously waiting for her mother, wondering why she ever thought her hair was something beautiful. It wasn’t like the other girls’, long silky brown or rich black. It was nothing but a frizzy rain cloud.

She wanted to go home and never leave again. Despite what her parents insisted, this school was nothing like her American school, with its colorful playgrounds and classrooms, where she could wear whatever she wanted. In America, she had chicken nuggets with Tater Tots and cookies.

Here, in Egypt, she had to wear a dark blue jumper over an itchy white-collared shirt. At lunch, she had two pâtés, biscuits, and a slice of flaky date pie. Though, if she was honest, she loved the date pie. If she was honest, she loved the lessons on hieroglyphs and the teachers. She was learning so much.

But the kids . . .

“There she is, Mommy! The freak!”

Ororo winced, peering over her shoulder, spotting two little boys pointing at her. Pointing at her thick, silver-white hair that came down to her tiny waist, covering her like a coat.

The boys’ mother glanced over, blinking back in surprise.

“My, what the devil is that?” she mumbled, hurrying them along.

Ororo bit her lip, fighting back tears, and combed her hair down over her face, using it as a shield.

If she was honest, the kids in her school were just like the ones in America.

“You have eyes like the sky, child.”

Ororo startled at the deep voice, looked up through the gate bars, and gasped, pushing away from it, eyes cast down to the ground. A large man stood on the opposite side, so large he blocked out the sun, his beige skin covered in a thin layer of sweat.

“Hello, dear one,” he said. “What is your name?”

She shook her head, refusing to look at him.

“Oh, come now, hmm? Surely you have a name.”

Ororo studied his shadow on the ground, noticing he was wearing a hat with a tassel that swung. Her tummy ached, like the time she’d eaten bad hummus. She couldn’t explain it, but the man’s very presence made her ill. She wanted him to leave.

“I’m not allowed to talk to strangers,” she mumbled, turning her back to him.

“Well, that is a shame. I just noticed you crying, and, my, what extraordinary hair you have.” He breathed in deep, sniffing the air around them. His lips smacked. “And your energy . . . Wherever did you—”

“Ororo!”

Ororo whipped around to see her mother, face bright, waving at her through the crowd.

“Mommy!” she shrieked, and ran. She dove into her mother’s waist, nuzzling into her stomach, feeling at ease for the first time all day.

“Oh my.” Her mother laughed, nearly falling back. “I am so sorry I’m late! Still getting lost in our own neighborhood.”

“Hello,” the same strange, raspy voice said from behind them. The hair on Ororo’s neck stood up. The large man must have followed her through the crowd. “I was just keeping your lovely daughter company. She seemed rather upset.”

Ororo buried her face in her mother’s coat, and her mother patted her back.

“Would you ladies care to, uh, join me for tea? I insist.”

Ororo carefully looked up, only at her mother’s face. Ororo didn’t like the stranger and she didn’t like tea. She just wanted to go home.

Mother smiled at the man. “That is kind, but no, thank you. It is about time for me to start dinner. My husband will be waiting for us.”

But the man pushed further.

“Really, I insist,” he implored, eyes fixed rabidly on Ororo. “Your daughter is . . . quite extraordinary.”

Mother straightened at the comment, gripping Ororo closer. She smoothed a protective hand over Ororo’s hair.

“Yes, she is,” she said curtly. “Have a good day, sir.”

He tipped his hat. “Same to you, madam. Same to you. I’m sure we’ll be seeing each other real soon.” He turned back to Ororo, an odd smile on his face. “Goodbye for now, dear one.”

Mother pulled Ororo along, scurrying down the busy street toward home. Ororo looked back. The man had disappeared into the crowd, yet she had the lingering sense that someone was still watching.

x

When they finally reached home, Ororo threw her backpack down by the door and sighed. It felt like a weight had been lifted from her shoulders. The world inside their home made sense, while everywhere else did not. Mother made her way to the kitchen to put away food from the market. Ororo pushed her hair back from her face and glanced toward Daddy’s office. She knew what she had to do.

She scuttled past the living room, where Daddy sat in his favorite leather recliner. Quiet as a mouse, Ororo crept into his office, slid open the top drawer of his desk, and grabbed her prize. She padded across the hall and into the dark bathroom, the floor tiles cool against her feet. Flicking on the light, she looked up at the mirror, chewing the inside of her cheek. Yes, this would do.

She climbed up to the bathroom sink and stared at her reflection, noting the determination in her features. With a deep breath, she tugged at a chunk of her hair . . .

“Ororo Iqadi Munroe! What on earth are you doing?”

Ororo’s blue eyes flared in the mirror with her arm frozen, a pair of black scissors held taut to her silver-white hair. Caught. She winced. How had she not heard her mother coming?

“Goddess help me with this child,” Mother called to the ceiling. She stomped into the narrow bathroom, snatching the scissors out of Ororo’s hands.

“Have you lost your senses?” She glanced back into the living room. “David, do you see what you daughter is attempting to do?”

Ororo let out a hmmph in frustration. “Of course he does, Momma,” she said, climbing down from the sink. “He has eyes.”

Daddy held in a laugh. “Well, she certainly has your Kenyan pragmatism,” he quipped before returning to his book on African theology.

Mother narrowed her eyes at him. “And your American stubborn foolishness.”

He took off his glasses and winked. “Touché.”

Mother couldn’t help but smirk in response. “So silly.”

Ororo frowned. “What does prag-maz-tism mean?” She hated not knowing things. Hated feeling like she was missing out. Her mother always said that even as a baby she’d stayed up until morning, never wanting to miss a thing.

“Never mind all that,” her mother muttered, dragging her out of the bathroom and into their colorful living room filled with art, books, musical instruments, gemstone-colored pillows, and plush Turkish rugs.

The early-evening breeze billowed through the curtains of their top-floor apartment that faced east, giving them a view of the Giza pyramids in the distance. It was why they’d picked the place. Daddy wanted to wake each morning and be reminded of their great leap to Cairo.

Mother sat on the leather sofa, placing Ororo in front of her so she could look her daughter square in the eye.

“Ororo, tell me: what on earth would make you want to cut your beautiful hair?”

Ororo wrung her fingers. “Because you and Daddy don’t have white hair. You have normal hair.”

Mother’s eyes softened. She glanced at Daddy, who softly closed his book.

“Sweetheart,” he said, “there’s absolutely nothing wrong with your hair.”

Ororo took in her parents, one by one. Both her mother and father had dark copper skin with brown eyes. While her father had jet-black hair he kept cut low, her mother had tightly curly brown hair.

Ororo’s own white mane stopped at her waist, like a cape draped around her back, and her eyes were a clear blue ocean. White jungle monkey.

“No one else has it,” she cried, tugging at her locks. “Why do I have to look like this?!”

Mother smiled at Ororo, reaching up to tuck a lock of white hair behind her ear. “You know, there are many women in my family who have hair and eyes just like yours.”

Ororo blinked in surprise. “Then where are they? How come I’ve never seen them?”

Mother hesitated, her eyes holding a strange sadness. “It’s . . . hard to explain.”

Ororo’s eyes filled with tears. “The other kids make fun of me. They call me a freak, and I don’t want to be a freak.”

Mother wrapped her arms tight around her daughter. “Oh, sweetie. I know it’s hard to believe, but your hair— It just means you’re special.”

“But I don’t want to be special. I want to be like everyone else.”

Mother laughed, wiping Ororo’s tears away. “My dear child, you were not meant to be like everyone else. You were meant to shine like the brightest star.”

“I don’t care!” Ororo cried, stomping her foot.

“Sweetheart, have I ever lied to you? Do I not always tell you the truth?”

Ororo thought of all the times her mother had carefully explained things to her. About how plants grew and flowers bloomed, and how stars were made. She nodded twice.

“So, trust me when I say one day soon, you’ll learn that when you are born different, it means you were meant to be part of something different. Something way bigger than anything you could ever imagine. A dream so big that it may scare you.” Mother smiled mysteriously. “That’s when you learn just how brave and powerful you can be.”

Ororo pushed a strand of hair out of her face and sniffed. “But why do I—”

A sudden boom made her mother jump to her feet. The sound rang through their apartment. Ororo tensed, the back of her neck prickling.

“What’s that noise?” she asked, gripping Mother’s waist.

Daddy slowly stood, facing the balcony.

“Mommy? What is that?”

“I’m . . . I don’t know.” Her mother’s arms tightened around her. “David?”

Daddy stared out the open doors, squinting into the darkness. He gasped as orange light filled the room, growing brighter, the noise deafening. He spun around, racing toward them.

“Get down! Get down now!”

“What’s happening?” Ororo screamed, gripping her mother.

“David?”

“DOWN!”

Mother yanked Ororo to the floor, throwing her body on top of her baby girl’s. Daddy curled himself around them as the room shook with a violent jolt, dust pluming. Her mother screamed. Then the roof and floor collapsed all at once.

x

Ororo peeled her eyes open at the sound of something churning nearby.

“Mommy?” she moaned. “Daddy?”

Blackness surrounded her. She couldn’t tell which way was up or down. She tried to move her arms, legs, and head. She could feel everything, but she somehow could not move. As if she were trapped inside a tight black box.