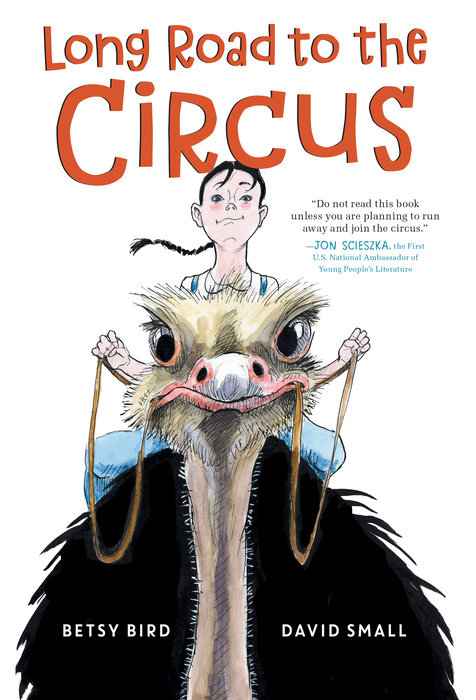

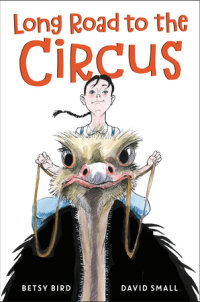

Long Road to the Circus

Author Betsy Bird Illustrated by David Small

Long Road to the Circus

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST CHILDREN’S BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY THE NEW YORK TIMES

The story of a girl who rides an ostrich straight to her dreams from the award-winning writer and librarian Betsy Bird, illustrated by Caldecott Medalist David Small.

"[A] charming, wacky novel." —The New York Times

Twelve-year-old Suzy Bowles is tired of summers filled with chores on her family farm in Burr Oak, Michigan, and desperate to see the world. When her wayward uncle moves back home to the farm, only to skip his chores every morning for mysterious reasons, Suzy decides to find out what he's up to once and for all. And that's when she meets legendary former circus queen Madame Marantette and her ostriches. Before long, Suzy finds herself caught-up in the fast-paced, hilarious world of ostrich riding, a rollicking adventure that just might be her ticket out of Burr Oak.

“Beautifully told by one of our best librarians.” —Jon Scieszka, First National Ambassador of Young People’s Literature

An Excerpt fromLong Road to the Circus

One

“Strongest grip in a girl I’ve ever saw,” Daddy said, not without some pride.

I looked down at my palms, rubbed raw where earlier I’d clung to the elm tree in our front yard with my no-good, stinking brother Bill pulling on my leg to get me down. He’d called me in for mealtime and I didn’t want to jump to obey his word, so there’d been a good five minutes of yanking and gripping before Daddy put a stop to it. I still wasn’t feeling anything in four of my fingers, but his praise was a cool, clear salve to those burning digits. A salve, that is, until Mama chimed in with “Just like the day she was born.”

Once she said that, no amount of moaning on my part could derail her from telling “The Legend of Baby Suzy,” and believe me, I’d tried. Changing the subject didn’t amount to anything. Lying about our cow going into labor didn’t do any good (possibly because she wasn’t pregnant at the time). Ignoring my petulance, Mama launched…

One

“Strongest grip in a girl I’ve ever saw,” Daddy said, not without some pride.

I looked down at my palms, rubbed raw where earlier I’d clung to the elm tree in our front yard with my no-good, stinking brother Bill pulling on my leg to get me down. He’d called me in for mealtime and I didn’t want to jump to obey his word, so there’d been a good five minutes of yanking and gripping before Daddy put a stop to it. I still wasn’t feeling anything in four of my fingers, but his praise was a cool, clear salve to those burning digits. A salve, that is, until Mama chimed in with “Just like the day she was born.”

Once she said that, no amount of moaning on my part could derail her from telling “The Legend of Baby Suzy,” and believe me, I’d tried. Changing the subject didn’t amount to anything. Lying about our cow going into labor didn’t do any good (possibly because she wasn’t pregnant at the time). Ignoring my petulance, Mama launched right in.

“The day you were born, lamb pie, you gave me more trouble than I’d ever had with your sister and brothers.” This was no small thing. Mama had three kids before me, and according to her, each one had been a trial. “I thought I knew all the ins and outs of birthing, but you gave me a real ride. You just didn’t want to leave! You were holding on for dear life to keep from meeting the world.” Then she began to laugh.

My mama cannot talk about the day I was born without bursting into giggles. Granny says it’s unseemly. That means whenever she gets to the hilarious part, Granny will totter over and start poking her with her cane, which only sets my mama off further.

“Get ahold of yourself, woman!” Granny says. “Birthing babies is our war! And telling the stories of it means telling about all the bloodshed and battles we overcame. Ain’t no time for tittering like a schoolchild.” Then she’ll poke me once upside the head with the cane and say, “You don’t see this one acting the fool when you tell that tale.”

I don’t think it much fair to get rammed in the head when I am doing something she likes, but that’s the way with Granny. Doing something right gets you one poke. Doing something wrong gets you a lot worse.

Anyway, the reason I wasn’t guffawing along with the rest of the family is because I’ve never found the story all that funny. And that’s on account of how Mama ends the story.

“Finally we get you out and there you are, smaller than a coop’s egg. This tiny little baby, all flailing limbs and wailing cry, looking half-starved, which is not the way a baby should be. But quick as lightning you latched on and started drinking on me, from the get-go. That’s when we knew you would do just fine.”

A pause.

“Except--”

“Except nothing,” I interrupted, not eager to hear any more. “And I ate everything you ever put in front of me and stayed small and that’s okay, the end.”

“Except,” she continued, like she hadn’t heard me, “when your granny came in to take you so I could rest--and truth be told, I was pretty tired as well--we tried to dislodge your tiny baby hands from my hair and clothes, and discovered a grip we’d never encountered before. Strongest thing I’ve ever felt from something that small.”

“Could be you just didn’t try hard enough,” Granny muttered to herself.

Mama shrugged at that. “I was plumb exhausted, I admit,” she said. “But the harder I tried, the harder you’d grip.”

Every single time, without fail, she’d start to laugh again. Laughing at the remembrance of laughing.

“There’s Granny looming over me, trying to take the baby Suzy away, and I just couldn’t get you loose. And then suddenly”--she snorted, which isn’t ladylike, but at this point she didn’t care--“I’m laughing too hard to dislodge you.”

“And then Granny gives it a try,” Daddy continued, because by this time Mama was having a high old gigglefest and wasn’t fit to talk, “and she can’t get you to let go either.”

“I tried,” Granny snapped. “But as soon as you got one hand undone, the other one would snake up and grab whatever was in reach.” She glared long and hard at me. “Like she was doing it on purpose.”

Not having anything to say to that, I said nothing.

Now Daddy was laughing too, along with my siblings. Even Bill was laughing, but that’s because he’s a nasty toad of a brother, and that look on his face wasn’t because he found the story funny but because he found my finding the story not funny, funny. Make sense?

“And then I tried to pull,” Daddy said, “and you just gripped your mama harder. I thought we’d have to take scissors to the dress just to cut you off.”

“And my hair!” Mama cackled.

Oh, they’re a regular funny troop, my family. I stood to leave, but Mama’s hand shot out and grabbed me. And if there’s any question of who I get my grip from in this family, they just need to feel that vise. You go nowhere.

“The thing is,” she said, calming down slowly and looking at me with real love, “I knew then that you were going to be one of my best and biggest problems, right from the start. Knew it like I knew your pretty face. ’Cause my girl’s the kind who never lets go of something when she wants it. Never.”

“Any fool can grip,” Granny spat. “It’s the smart ones that know when to let go.”

Well, there you have it. My name is Suzy Bowles and I’ve never known when to let go a day of my life.

Two

Let me tell you something about the summer of 1920 in Burr Oak, Michigan. So far it had been a nice round year with not a lot happening. In fact, I had good reason to suspect that as summers went, this one was shaping up to be among the dullest. President Woodrow Wilson was in office, but according to Mama and Daddy, he wasn’t doing a whole lot of stuff, and that’s just the way they liked it. Unfortunately, the very stuff he wasn’t doing was causing some problems for our farm. Seemed like a lot of folks in town were out of work, which was just weird to me, seeing as in farm country, land’s all around. Someone has to till it. What was stopping them?

Case in point, Uncle Fred. Wait. Stop. I got that all wrong. According to our neighbors and friends and pretty much any lady I’ve ever passed on the street for the better part of my short life, his name is actually Lazy Old Fred or Good Ole No‑Good Fred or even Deadbeat Fred, which has a nice ring to it alongside its not-too-nice meaning. Uncle Fred was one of those folks out of work. That wouldn’t have been much of an anything except, somehow, he was married now with a kid, and if he didn’t work and his wife didn’t work and the baby didn’t work (naturally), then nobody was working and everyone was starving. Plus, he was Daddy’s brother and all, so the solution seemed simple. Uncle Fred was gonna come to our farm to be a farmhand. Not much in the way of pay, but free food and a place to sleep. Not too shabby.

Our farm’s pretty good as they go. It’s not all that big. We’ve only got a few cows and chickens and horses and sometimes a goat or a pig or a sheep or two, but the crops are decent and that’s where Daddy and his hired crew spend most of their time. That’s where Uncle Fred was going to spend his time too, when he came. Which he did in just the strangest way.

I wasn’t paying all that much attention when Unlce Fred, Aunt Juliet (that’s his wife), and little Catalonia stumbled onto our property. Someone had mentioned they were coming, but I don’t think I heard it at the time on account of the fact that my brother Bill kept whispering to me all breakfast that there was no way I was gonna be able to keep that toad I’d caught the day before. Bill’s two years older than me, and he’s the closest to my age on the farm. The rest of my siblings are all okay. I keep out of their way and they keep out of mine. Except Bill. I know we’re supposed to love our brothers (which they say in church ALL the time) like ourselves, but there ain’t no way to love Bill. He is unlovable. Something’s not right with him. Mama loves him, but I think she’s the only one who does. Daddy pays so much more attention to Ernest, who’s big and strong and does what he’s told, that he ignores Bill half the time, and for the other half he’s yelling at him for some prank he pulled or job he didn’t do. It’s what makes the boy such a mean son of a gun. Or why he’s the worst to me. Particularly when it comes to pranks involving food and slimy worms.

Now, if it happened to anyone else, I might almost admire Bill for managing to get five of those crawlers onto a single breakfast plate without anyone seeing. The problem was, it was my plate, and under usual circumstances I really, really like Mama’s scrambled eggs. Then there’s the fact that I came dangerously close to shoveling one of those thick, bluish worms right down my gullet, and it’s a miracle I saw the telltale wiggle in time.

I’ve found that when it comes to handling Bill, actions speak louder than words. That’s why I perched myself on the porch roof when he wasn’t looking and then balanced one hand down on the trellis. With my feet hooked on a strong-but-loose roof tile, I was in the perfect striking position. My mission was one of revenge.

I imagine the scene that met my uncle, aunt, and tiny cousin as they came up the drive that day was probably as close to a full-blown family carnival as they had ever hoped to see. There I was, the lower half of me on the porch roof and the upper half gripping the trellis with one hand and Bill’s ear with the other. It’s a pity they hadn’t seen my lunge. I’d whipped out fast, like a water moccasin nabbing a frog, and Bill was howling practically before I started digging my fingernails into him.

“NEVER PUT STUFF IN MY FOOD AGAIN!” I screamed at him. He was doing his own fairly good worm imitation, writhing and wiggling under me, but I’d wedged my feet so well into the roof that I wasn’t budging for anything. Besides, he knew my hands don’t let go until I tell ’em so. Each one of my joints has a little lock in it, and only I know the combination.

“I won’t do it again, I promise!” he howled, but we both knew he was lying.

“Actually promise!” I howled right back, but by now he’d seen our relatives standing, shocked, at the bottom of the stairs. He stopped caterwauling all of a sudden, and, confused, I strained my neck up to see what the heck had distracted him from my vengeance.

“Ah, hello,” said the man. He was a raw-boned, unhappy-looking fellow. All hunched up at the top and floppety down below. His wife was pretty but looked like she was just half a second from getting old too soon. And the baby? They pretty much all look the same to me until they’re able to string four words together.

Bill took advantage of my surprise and managed to pry my thumb and forefinger apart for half a second before I felt what he was doing and double-quick grabbed him again. He screamed bloody murder, and then the rat appealed to the man standing before us.

“Please, Uncle Fred, save me!” he said.

Uncle Fred? I’d heard Daddy talk about him for years but had never seen him in the flesh before now. He was what they call a black sheep in the family or something. One of those fellows born here in Burr Oak who took off for parts unknown all around the country. To hear Daddy and Granny tell it, he was never satisfied in one place. Just kept bouncing and bouncing all over until, with all that bouncing, he somehow found himself a wife and child. Looked like he was finally bouncing back here again for some reason.

I vowed at that moment to find out more about the man. I had a boring summer before me. Might as well solve a tiny mystery or two.

Bill continued to whine. “Tell her to let go.”

Uncle Fred looked me dead smack in the eyes and said, “Suzy. Let go of your brother now.” I looked back, feeling defiant, but he hadn’t said it in a mean or superior way. Just a conversational manner that made you think twice about being a hooligan in his presence. I dropped the ear, Bill went like lightning into the house, and Aunt Juliet looked plumb frightened by the whole ordeal.

“Juliet, why don’t you take Catalonia into the house to meet my ma?” Uncle Fred said. “She’ll be happy to welcome you when you do.”

Aunt Juliet gave just the barest of nods, then ducked her head down and scurried into the house. I wondered if she spoke at all or if she was more of the nodding and scurrying type. Takes all kinds.

Uncle Fred, for his part, just looked up at me, dropped his head, then settled down onto the top step of the porch.

“Need your help, girl, if you’re able.” No more words after that. Curious, I scrambled down the trellis and stood before him. When he saw me, it was like he knew I’d come no matter what. Then he pointed to the top of his back on his right side.

“Saw you have strong hands. I’ve got a knot so big I can hardly lift my arm right now. Need you to pound it away with whatever strength you have.” He paused. “Give you a nickel if you do.”

My eyes brightened. A nickel! For doing to Uncle Fred’s back what I’d done to my brother’s ear for free? Without a word, I bounded up the porch steps and looked where he’d been pointing. As I did, I thought back to some of the offhanded comments I’d heard my daddy make about his brother over the years. “Can’t hold on to his money for two minutes without it burning him,” he’d say. “It’s like his skin boils on contact with good honest cash. The minute he has it, he just has to get rid of it.” Then he’d shake his head and give this little laugh like it was kind of cute, even if it drove him wild. “That man’s never happier than when he’s broke.”