Classic Slime

1 eight-ounce bottle of white glue

1 tablespoon of baking soda

1/2–2 teaspoons of contact lens solution

A few drops of green food coloring

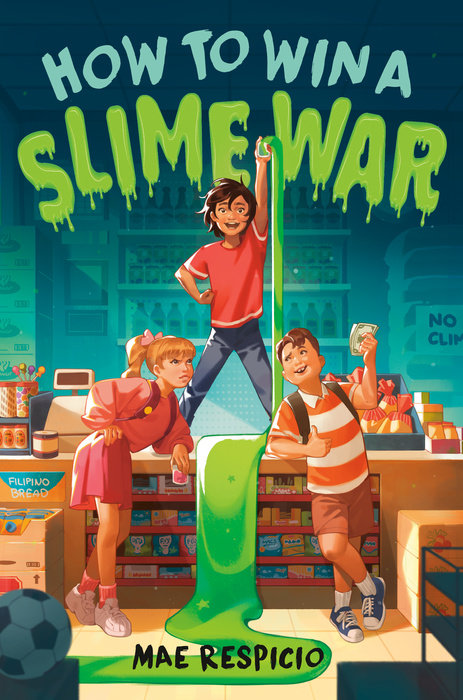

The world has plenty of twelve-year-olds who’ve accomplished amazing things, like:

Hoisting 308 pounds in one clean lift.

Inventing a braille printer from a Lego set.

Making millions of dollars from candy that’s good for your teeth.

I wish I could add myself to this list, but I can barely lift a fifty-pound bag of rice, when I play with Legos I usually lose the pieces, and when it comes to candy--especially my favorite kind, with an edible wrapper--I’d rather eat it than sell it.

I do have one hobby I’m not bad at:

Making slime.

I’m stellar at slime challenges. This morning my best friend, Raj, and I are doing one final face-off before my dad and I move from San Jose to Sacramento. It’s our way of saying goodbye.

I lay out the ingredients, a couple of bowls, and some fat wooden stirring sticks. Raj sets my laptop on the kitchen counter, raises the volume, and cues up a video:

Slime Time Soraya’s 30-Second Challenge!

He rubs his hands together. “I’ve been waiting the whole week for this!”

We’ve done all her challenges except this one, which we’ve been saving for a special occasion.

“Okay, Slime Squad!” Slime Time Soraya says on-screen. “Today we make . . . classic slime! Your goal: mix as fast as you can.”

“Challenge accepted!” Raj says back.

“Who makes good slime in thirty seconds?” I say. “Art takes much longer than that.”

Raj smiles slyly. “You’re not the only one with skills, Alex.”

We get into position and Soraya counts down:

“Three, two, one . . . GO!”

We squeeze glue into our bowls. Shake in baking soda. Squirt in food coloring. Green, of course.

“Stir, slimers, STIR!”

I mix in quick circles. Raj looks like he’s beating eggs. My bowl whirls around, I can’t keep it still. The timer ticks loudly and we stir even more frantically.

“Time’s up! Sticks down!” she says. We throw down our craft sticks and let out a huge sigh.

I look at Raj--his glasses are covered in drops of green glop--and we burst out laughing. At school I don’t have many friends, but I can count on Raj. I’m going to miss him. My dad and I are moving into Lolo and Lola’s house, right next door to my cousins, while our grandparents are away on their retirement trip. I’m nervous but excited--Dad and I are taking over Lolo and Lola’s Asian market. I’ve always wanted to have my own business.

Raj scoops up his slime and lifts his stick high. Goop drips down his wrist. “Gross. It didn’t congeal at all.”

“Told you we needed more time.”

There’s baking soda on my cheeks and slime hanging from my long hair, too. We take one look at our mess and crack up.

And then Dad walks in.

“Hi, Mr. Manalo.” Raj waves but forgets he’s still holding his stick. More goo flings on the counter and floor. “Whoops.”

“Hey there, Raj.” Dad gives him a smile, but it disappears when he turns my way. “Alex, we’re supposed to be packing, not making more work.”

“We’ll clean it up, Mr. Manalo. We promise,” Raj says. He crosses his heart with the stick and accidentally smears goop on his shirt. I try to hold back my laughter. It’s lucky Raj is here, otherwise Dad would have gotten mad. He doesn’t think sliming’s productive (and he hates the cleanup).

Dad nods and goes to do more packing.

“Are you nervous?” Raj asks as we wipe everything down.

“About what?”

“About being the smallest kids in sixth grade!”

Raj and I both got stuck with short genes. I don’t remember my mom--she died when I was little--but Dad describes her as petite. He’s average height, so out popped me: Alexander T. Manalo, short-kid, science-loving, sports-failing entrepreneurial slimer.

Before I found out about our move, Raj and I decided we would work our way up to the popular table in middle school. He didn’t think we could do it. He thought we had to be taller and sportier and way cooler for it to ever happen.

“Why would I be nervous?” I ask as we put everything away. “I’m launching the new me.”

“How? By sliming?”

“Don’t be so sure, Raj. Things can change.”

He snickers, but it makes me think.

It seems impossible that greatness could be achieved by turning glue into goo, but it’s happened--Slime Time Soraya and other kids have literally made millions on tutorials and challenges.

Maybe I can, too. Maybe one day I’ll make sliming work for me.

All I need is my chance.

Super Stretch

1/2 cup of white glue

3–4 cups of shaving cream

Sprinkle of baking soda

3–4 drops of food coloring

3 squirts of baby oil

Beads, confetti, or any other fun mix-ins

In Lolo and Lola’s kitchen, I shake a can of shaving cream and squirt it into a plastic tub, circling until it peaks into a tall, foamy mound. The last time I made this slime Dad got mad since I used his whole can, but he won’t miss it. Even though it’s been a few weeks since we moved, there are still boxes and packing paper scattered all around.

The glob doesn’t look like much until suddenly--it does. Because here’s what happens: white glue’s a polymer--a molecule with thousands of atoms--and when you combine it with certain ingredients and give it a lot of care, they stick to each other. They turn into something new.

Slime.

I make all kinds: butter slime, crunch slime, sand slime; glow-in-the-dark slime, and one time, an edible batch that tasted like juicy watermelon! Sometimes I create rainbow colors. Other times I plop in teeny beads so it feels unexpected as you’re squishing.

There. Finished.

This batch sticks to the bottom of the bowl until I ball it up. I knead it like bread, then pull it like taffy as wide as it’ll go--the length of my arms.

I twist it up until it fits neatly into a small, clear container and the bright green shines through.

Hmm. What should I call this?

I write out a label and slap it onto the lid:

Super Stretch.

“Alex! Let’s get going!” Dad yells.

I peek my head through the kitchen door. Dad’s waiting with a big smile.

“I’ll get my helmet,” I say.

“How about we drive? There’s a box I want to bring home from the store.”

“It’s okay, I’d rather bike,” I say. “Meet ya there?”

Dad nods. I strap on my helmet and head out.

I’m finally getting used to it around here. It’s different from our old home, where we lived in a tall condo on a busy street, surrounded by giant tech companies and endless lines of electric cars whizzing by.

Here I roll past boxy houses with trim lawns.

Past a packed coffee shop, a bustling tire shop.

Past a grassy park of smiley people walking their dogs.

My grandparents’ store isn’t far from the house. I mean our store--I still have to get used to saying that. On the way I stop under a large, leafy oak in the park. Sunlight peeks in through the trees and makes cobwebbed shadows on the pavement.

I stare at a building across the street.

golden valley middle school

I’ll start sixth grade there tomorrow. I’m somewhere between ready . . . and petrified.

My old school had boys twice my height who called me by the wrong name--Allen, Felix, Alec. They made fun of me for “playing with boogers at lunch” when I brought an oozy batch to school. Everyone laughed. We were jealous of the attention people gave them, but mainly we were curious. What was the big fuss about being popular?

Now I start fresh.

I get rolling. In a few minutes I reach a corner of shops. Some boys around my age are biking through the parking lot, too. I wish I had friends to goof off with already.

My family’s market is in a little strip mall, along with a mailbox and shipping place, a nail salon, and an empty storefront with a for lease sign. Across the way is a similar-looking block but with fancier shops like an olive oil store that sells every flavor of olive oil (why?) and a store that sells unfinished tree stumps (also why?). We’ve seen lots of businesses come and go, but my family’s has been here the longest.

I sling off my helmet, lock up my bike, and push through the glass doors. A bell jingles and a sign says:

new and improved manalo market coming soon!

This is the whole reason we came here--and I’m ready.

CEO

Sunlight floods the store through floor-to-ceiling windows. Dad grew up in the market, and I’ve spent a lot of time here, too, while staying with my grandparents on the weekends during school or sometimes the whole summer. Twelve years of the same happy memories: people coming in and out, the smell of savory Filipino food, and a bright mix of languages and laughter. Whenever I walk in I always have the same feeling--of home.

The market has a small seating area and aisles stocked with local and imported food and trinkets from China, Korea, India, Japan, Thailand, and the Philippines. There’s a packed, colorful row of candies and crackers, and guava juice boxes that go tastily with salty dried squid snacks. One wall is stacked with pallets of giant rice sacks and has a no climbing sign. True story: that sign’s there because of me and my cousins. It’s one of our favorite things to do.

I zoom past the rice wall and smack the bags like drums. Dad’s behind the counter ringing up a mom and her little kid. A small TV plays Filipino soap operas in a steady hum of Taglish--Tagalog words mixed with English. We don’t really watch the shows, but since we miss Lola, we keep it on.

“How are your parents doing?” the woman asks my dad.

“Oh, they’re loving retirement,” he says. “They’re in Hawaii now. Then they’ll be in Alaska, and back here again for an RV trip up the coast.”

The register bings and Dad hands her some change.

“Hold on, don’t leave yet,” I say to the lady, and I reach under the counter for a small box of candy. I pull one out. It’s peach-colored with a clear wrapper, and I hold it up to the boy. “Do you dare me to eat this . . . with the wrapper still on?” The kid’s eyes widen, and before he can answer I pop it into my mouth. The rice paper melts on my tongue.

“For you,” I say, and I hand him the whole box.

“Thanks, guys, see you soon,” the mom says, waving, and the doors swing closed.

“Do you know her?” I ask.

Dad shakes his head. “Probably a regular.”

Everyone around here loves my grandparents. They trust them. Plus Lolo always gives treats--candies or almond cookies or sweet rice cakes wrapped in banana leaves that Lola bakes--to any cute kid or neighborhood buddy who drops by. “It’s never something for nothing, Alex,” he likes to say. “Owning a store is about building relationships.”

Dad grabs a clipboard and begins roaming the aisles, making notes.

I slide my backpack onto the empty takeout bar, which used to sell fresh, steaming-hot Filipino dishes. We’re bringing it back, bigger and better. It’s on Dad’s list somewhere.

The store stocks everything else, too, all the “normal” items, which some people ask for when they come in. When I ask, “What do you mean by ‘normal’?” they say cereal or toilet paper. Seems strange. What we carry is normal to people who need it.

Mainly we carry Filipino food: bottles of salty fish sauce and jars of sweet ube, a purple yam, all in neat, bright rows, and a big basket with bags of my favorite Filipino bread, sweet pandesal. The produce section has crates of calamansi, a small green-and-yellow Philippine citrus fruit, plus saba--short, squat bananas that hang like sunshine from hooks.

In the Philippines, Lolo and Lola owned a sari-sari store. It means “variety,” although Lola says it means “community.” Her favorite memory of running their sari-sari was when everyone in town would come to shop and then stay the whole day chatting and eating, like a family party.

When my grandparents came to California in the 1970s, Lolo wore bell-bottom pants and Lola had fluffy black beehive hair, and they couldn’t find any place to buy fish sauce--so they opened Manalo Market. It was successful for a long time, but lately it hasn’t been doing as well. My grandparents wanted to sell the store and retire, when Dad and I stepped in. We had a family meeting about it.

“We’d like to take over,” Dad told my grandparents. “Right, Alex?”

I nodded. I’ve always wanted to run a business.

Lolo and Lola turned to each other and Lola cried happy tears. Dad worked for a huge tech company that invents apps and other digital things. His sister, my Auntie Gina, runs her family’s successful physical therapy clinic. Both of them have always said they never wanted to inherit the market.

“I’m ready for a change,” Dad said.

There was more to it, like how Dad broke up with a lady named Revi who I thought might become my stepmom, and how he hated his job staring at computers all day. I liked Revi. The three of us had fun together, and Dad didn’t stress out about work when she was around. But I hated his job, too. He worked long hours, and I had a ton of different sitters.

“You’ve made me very proud, son,” Lolo said as they shook on it. No hug, pure business. Dad’s not big on hugging.

All morning we hear the store’s steady song of the front door jingling and people shopping.

A lola taps on the watermelons and listens close for the perfect hollow sound.

A woman in a suit bags green onions and bok choy, then grabs two Chinese newspapers from a tall stack near the door.

Teenagers giggle and try to steal a pack of gum until Dad gives them his don’t-even-try-it look and they pay and say sorry.

Next comes a man I recognize--Paolo, a friend of my grandparents.

“There they are, my favorite Manalos,” Paolo says. “But don’t tell your lolo I said that.”

A dollar bill hangs near the register from our store’s first sale, and it’s Paolo’s. He moved to the neighborhood from Brazil around the same time that my grandparents opened the market. He ate his first Filipino meal here--sticky garlic rice and pork adobo. Once a week he still comes in for lunch and a lottery ticket.