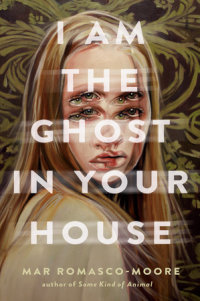

I Am the Ghost in Your House

Author Mar Romasco-Moore

From the author of Some Kind of Animal comes a wildly unique story about an invisible girl struggling to see herself in a world obsessed with appearances.

Pie is the ghost in your house.

She is not dead, she is invisible.

The way she looks changes depending on what is behind her. A girl of glass. A girl who is a window. If she stands in front of floral wallpaper she is full of roses.

For Pie’s entire life…

From the author of Some Kind of Animal comes a wildly unique story about an invisible girl struggling to see herself in a world obsessed with appearances.

Pie is the ghost in your house.

She is not dead, she is invisible.

The way she looks changes depending on what is behind her. A girl of glass. A girl who is a window. If she stands in front of floral wallpaper she is full of roses.

For Pie’s entire life it’s been Pie and her mother. Just the two of them, traveling across America. They have slept in trains, in mattress stores, and on the bare ground. They have probably slept in your house.

But Pie is lonely. And now, at seventeen, her mother’s given her a gift. The choice of the next city they will go to. And Pie knows exactly where she wants to go. Pittsburgh—where she fell in love with a girl who she plans to find once again. And this time she will reveal herself.

Only how can anyone love an invisible girl?

A magnificent story of love, and friendship, and learning to see yourself in a world based on appearances, I Am the Ghost in Your House is a brilliant reflection on the importance of how much more there is to our world than what meets the eye.

An Excerpt fromI Am the Ghost in Your House

1

The train to Pittsburgh was going backward, undoing all the distance we’d covered.

My mother had fallen asleep, head slumped against the window. Through her transparent body, I could see the landscape rushing past in reverse. Images flickered across her face: tree trunks, mountainside, sky. It made her seem restless.

“Mom,” I whispered, nudging her.

The plan was to spend only one day and night in Pittsburgh, then catch a train for New York the next morning, so I was impatient to get there. Worried we never would. It wasn’t as if we’d paid for tickets, at least. My mother and I don’t need tickets.

We just need to be careful no one sits on us.

The sun was rising. Out the window, I recognized a river, which, half an hour before, had been indistinguishable from the night sky. Now it was a cloudy green, broken by red rocks trailing lacy veils of foam. Everything looked sharp in the morning sun, as if the train window were a movie screen. But the movie made no sense. Something arty, experimental. Short…

1

The train to Pittsburgh was going backward, undoing all the distance we’d covered.

My mother had fallen asleep, head slumped against the window. Through her transparent body, I could see the landscape rushing past in reverse. Images flickered across her face: tree trunks, mountainside, sky. It made her seem restless.

“Mom,” I whispered, nudging her.

The plan was to spend only one day and night in Pittsburgh, then catch a train for New York the next morning, so I was impatient to get there. Worried we never would. It wasn’t as if we’d paid for tickets, at least. My mother and I don’t need tickets.

We just need to be careful no one sits on us.

The sun was rising. Out the window, I recognized a river, which, half an hour before, had been indistinguishable from the night sky. Now it was a cloudy green, broken by red rocks trailing lacy veils of foam. Everything looked sharp in the morning sun, as if the train window were a movie screen. But the movie made no sense. Something arty, experimental. Short on plot.

Mother shifted and groaned softly in the seat beside me.

“We’re going backward,” I told her.

“Must be a freight train on the tracks.” She waved a dismissive hand. “They have right-of-way.”

In the seat behind us, a child started crying. I wanted to cry, too. It was silly and selfish, but I thought maybe the universe was conspiring to keep me away from Pittsburgh. The last time we’d been there, two years ago, things ended terribly. That was my fault, and Mom had told me in no uncertain terms that we were never, ever going back.

But I wanted to go back. I’d been wanting it every day for the last two years.

There was someone there I needed to see.

“I feel ill,” my mother said, still curled up with her head against the train window. “Be a dear and fetch me a ginger ale.”

“Okay,” I said. “Of course, right away.”

When Mom had finally given in and agreed to a brief Pittsburgh detour, it had seemed, perhaps, too good to be true.

Today, if the train ever started moving the right way again, we’d stop by the City of Bridges, and then tomorrow we’d go to New York City to celebrate my favorite day of the whole year. Not my birthday--that had already happened. Tomorrow was far better than my birthday, far better than Christmas.

Tomorrow was Halloween, the one day of the year that I could be seen.

Not because of magic or anything. Halloween is just the only day it’s acceptable to wear a full-face mask without everyone assuming you are about to kill them. People could see the mask, but not my face.

I was born invisible.

Really invisible. Not just shy or overlooked. Not like a superhero, either. I couldn’t turn it on or off.

Nobody in this world had ever seen my actual face, except for my mother, who was invisible, too. She saw me the same way I saw her, the same way I saw myself in mirrors. To her, and to myself, I looked like I was made of glass or water. Insubstantial. A girl who might break or wash away.

To anyone else, I looked like nothing.

I’d never had a job or a car or a friend. My mother and I roamed, taking what we needed, living in other people’s houses like ghosts.

We had been formally exorcised, in fact, six times.

On the backward train, I stood and made my way down the aisle. We took trains because they have more space. Buses are like moving sardine tins. Airplanes, I imagine, are even worse.

I pressed my gloved hand against the automatic door panel at the end of the train car. We are invisible but not insubstantial. The door didn’t know the difference between me and someone normal. One old Mennonite woman glanced up as the door rattled open for--from her perspective--no one, but this early, most passengers were asleep.

In the tiny metal no-man’s-land between cars, the muted rumble of the train became a clanking, wailing, whistling roar. On crowded trains, my mother and I were occasionally obliged to spend most of the trip in these thunderous spaces where the floor and the ceiling and the doors all rattle like wild. The wind wants to get in, wants to ride for a while.

In the café car, a conductor was sitting on one of the blue padded benches, eating a muffin. He frowned through me as I came in.

“Is that door broke?” he called to the café man, who shrugged.

The train shuddered to a stop, and I lost my balance, banging my hip against a booth. The conductor grumbled about the “goddamn freight trains” clogging the tracks.

I crept past him to the counter and pulled off one of my gloves. They were lilac silk with pearl buttons, lifted from a vintage shop in Chicago.

When the café man turned to wipe down the microwave, I hefted myself up onto the counter, reaching out with my bare hand for the stacked soda cans on the shelf behind it. The moment my fingers brushed against a can, it went filmy, translucent, as see-through as me. To the conductor and the café man, had they been looking, it would have disappeared.

That’s how it works. That’s why I always wear gloves. Anything that touches my bare skin turns invisible, too. For Halloween, I have to wear two masks, one on top of the other, because the first one will vanish.

My mother says that we are controlling this effect, on some level, but unconsciously. It’s a reflex, like flinching when touched. Sometimes my mother can control it a tiny bit if she concentrates super hard--can cause, for instance, only one small part of an object to become invisible--but I’ve never managed.

Ginger ale acquired, I slipped back out of the café car. Behind me, the conductor cursed “this run-down hunk of junk.” We were still at a dead stop.

Mother was slumped forward in the seat when I reached her, head cradled in her hands.

“Mom?” I said quietly.

She glanced up, face pale, which is to say more see-through than usual. Out the window behind her, a hawk landed on a tree alongside the tracks, perched directly in line with her right eye.

We don’t reflect any visible light, for the most part, though Mother says if we stood stock-still against a white wall, a close observer might spot a slight darkening of the air where our pupils are. But she and I can see a fraction of the spectrum that normal people can’t. It means we see better in the dark, because there’s a haze of infrared around anything living, anything warm. That’s why I can see her, though faintly, and she can see me.

It’s always been that way.

I tried to hand her the ginger ale, but she blanched, turned away, and clutched her stomach. I thought she was going to puke, but she didn’t.

Instead, she disappeared.

A Small Town Somewhere Near Lake Michigan

Unlike me, my mother wasn’t born invisible. It came on, like a condition, in adolescence. At ten, she told me, her invisibility first manifested, during a trip to the lake. She remembers standing at the edge of the water. Just a few feet away, her father yelled her name, but his eyes passed right over her. For a few wonderful moments, she was safe.

At first, her invisibility would come on unpredictably, last for a few hours, fade. The duration and frequency increased over the years until, by the time she was fourteen, it was permanent. Irreversible.

Not that she had any desire to reverse it.

My mother believes it was a defensive adaptation. Protective camouflage. Because already, by that age, she was being seen in ways she didn’t want to be.

I have never met my grandparents and I never will. My mother doesn’t like to talk about them. They weren’t good parents, weren’t good people.

At fourteen, as soon as she could hide from them, as soon as she could get away, she did. From then on, my mother took care of herself, haunting the houses of the rich, taking what she needed. She never finished high school, but she read voraciously, sat in on college classes. Learned all she could. Traveled. She was self-sufficient. Alone.

Not counting, of course, the five or so years she spent being an international art thief with my father.

She says she regrets those years now.

Never fall in love, she always tells me. It isn’t worth it.

Well, too late.

2

I stared at the empty seat beside me on the train, which was supposed to be going to Pittsburgh but at that moment was going absolutely nowhere.

My mother is dead. That’s the first thought that popped into my mind. It didn’t make sense, but neither did what I’d just seen.

Maybe this was what happened when people like us died. I’d always assumed we died the same way as everyone else, but it wasn’t like I had proof.

My mother had told me she didn’t know if there were any other invisible people out there. We hadn’t met any. It might just be the two of us. Alone in the world.

Except not entirely alone. We had each other, at least.

That was all we had.

Panicked, I clutched at the empty air where my mother had been. But it wasn’t empty. My knuckles collided sharply with her shoulder.

She stuttered back into view.

“You hit me,” she said, brows furrowed.

I gaped at her. A moment later, she doubled over and vomited onto the floor.

We always spoke quietly to each other on trains. The muted rush of air and clatter of wheels on tracks was usually enough to hide our words. But Mother’s retching sounds were loud. A sharp acrid odor jammed itself up my nose.

“Aw, hell no,” said the woman in the seat behind us. “Riley, you being sick over there?”

“Nuh-uh,” called a kid from across the aisle.

I shoved the ginger ale into my backpack. My mother had figured out a system years ago: we cut slits in the shoulders of our shirts, then threaded the backpack straps through so they would touch our skin at all times and thus keep the packs (and everything in them) invisible.

My mother was wiping her mouth with a shaking hand. I waved urgently toward the far end of the train car. She nodded and followed me down the aisle into the larger of the two bathroom compartments. I slid the heavy door shut, latched it.

“What the hell is going on?” I asked her, trying to keep my voice level.

She leaned against the wall by the sink, eyes shut, one hand on her stomach. The train lurched back into motion beneath us. Going the right way this time, it felt like.

“Mom?”

Her eyes fluttered open. She reached toward the sink, cupped her hand under the faucet. “Turn it on for me, will you?”

I wanted to refuse, to yell at her for scaring me like that, but I knew that was a selfish, childish way to act. I was seventeen, nearly an adult now, so I reached forward, pressed the faucet button. Water dribbled out, gathering slowly in my mother’s glassy palms. She rinsed her mouth. Rinsed it again.

“I’m sorry, baby,” she said finally, straightening up. “I guess I got motion sick.”

Which was bullshit. I’d been riding trains with her all my life, and she’d never gotten motion sick. We rode for days sometimes. Weeks.

“You disappeared,” I said accusingly.

“Oh.” A series of expressions ghosted briefly across her face. “I didn’t realize.”

I realized, though. Understood those flickers of emotion. She wasn’t shocked, wasn’t panicked. She knew. This wasn’t the first time. I felt a flicker of rage.

“This has happened before?” I asked, far louder than usual. Loud enough that someone could have heard. I knew I wasn’t being fair. She was sick, obviously. Something was wrong with her. I should be nice to her, not angry with her.

She frowned, seemed to consider lying, which was answer enough.

“When?” I demanded. “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Keep your voice down.”

“You’re the one who puked loud enough for the whole train car to hear.”

She sighed and rubbed her eyes. Was she more translucent than usual? I wasn’t sure. I could read the be considerate of your fellow passengers, don’t leave a mess sign clearly through her left shoulder.

“What’s wrong with you?” I asked.

“I’m fine,” she said, another obvious lie. “I just need to rest.”

We had been moving around a lot lately. But that wasn’t unusual.

We are restless people by nature. We roam, from one house to another, one city to the next. There is a limit to how long we can stay somewhere before people start to notice. Even when we find an empty house, there is always the risk of the owners returning, or new buyers moving in, or (as happened exactly once) waking up to a wrecking ball smashing through the front window.

“You aren’t fine,” I told her. “That was scary.” An understatement.

“Pie,” she said, which is what I went by, since the name she gave me was too sad. “We can talk about this later.” Her voice took on the hard edge of a maternal lecture, the same tone in which she had so often said, We are never going back to that city, Pie, and you know why. “Let’s find a house as soon as we get in. I feel like I’ve barely had time to close my eyes the last few weeks.”

I frowned at her. Three weeks ago had been my birthday, which we’d celebrated on the coast of California in a condemned beach house. My mother had gathered seventeen miniature cakes from various bakeries, and I’d taken a single bite out of each.

My birthday gift, she told me, was that I could choose where we went for a while. Which was unusual. I was used to my mother being in charge. Always following her where she wanted to go, following her many rules to keep us safe and undetected.

Do not wander off. Do not walk in snow or sand or gravel or mud or loose dirt. Do not exhale too much outside when the temperature is below freezing. Avoid walking in precipitation of any kind. Avoid smoke. Never get in a pool or other body of water in view of others. Do not sit on a soft surface unless alone. Never touch anything with an ungloved hand when someone is looking. Never move anything with a gloved hand when someone is looking. Do not take anything with a security tag. Do not take anything too personal or too ostentatious. Take only what you need. Be quiet, be quiet, be quiet. Never speak when someone can hear you. Never touch them. Never let anyone, in any way, know that you are there.