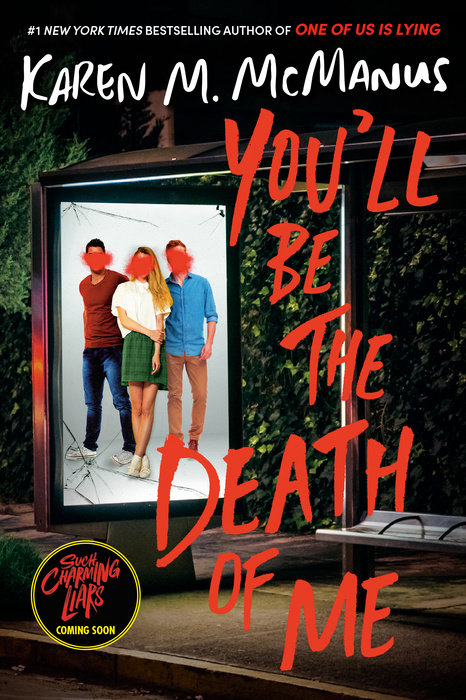

You'll Be the Death of Me

Author Karen M. McManus

You'll Be the Death of Me

#1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • From the critically acclaimed author of One of Us Is Lying comes another pulse-pounding thriller. It's Ferris Bueller's Day Off with murder when three old friends relive an epic ditch day, and it goes horribly—and fatally—wrong.

Ivy, Mateo, and Cal used to be close. Now all they have in common is Carlton High and the beginning of a very bad day. Type A Ivy lost a student council election to the…

#1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • From the critically acclaimed author of One of Us Is Lying comes another pulse-pounding thriller. It's Ferris Bueller's Day Off with murder when three old friends relive an epic ditch day, and it goes horribly—and fatally—wrong.

Ivy, Mateo, and Cal used to be close. Now all they have in common is Carlton High and the beginning of a very bad day. Type A Ivy lost a student council election to the class clown, and now she has to face the school, humiliated. Heartthrob Mateo is burned out from working two jobs since his family’s business failed. And outsider Cal just got stood up . . . again.

So when the three unexpectedly run into each other, they decide to avoid their problems by ditching. Just the three of them, like old times. Except they’ve barely left the parking lot before they run out of things to say. . .

. . . until they spot another Carlton High student skipping school—and follow him to the scene of his own murder. In one chance move, their day turns from dull to deadly. And it’s about to get worse. It turns out Ivy, Mateo, and Cal still have some things in common...like a connection to the dead kid. And they’re all hiding something.

Could it be that their chance reconnection wasn’t by chance after all?

Look for the third book in the One of Us Is Lying series--One of Us Is Back!

An Excerpt fromYou'll Be the Death of Me

1

Ivy

I respect a good checklist, but I’m beginning to think my mother went overboard.

“Sorry, what page?” I ask, flipping through the handout at our kitchen table while Mom watches me expectantly via Skype. The heading reads Sterling-Shepard 20th-Anniversary Trip: Instructions for Ivy and Daniel, and it’s eleven pages total. Double-sided. My mother planned the first time she and Dad ever left me and my brother alone--for four days--with the same thoroughness and military precision she brings to everything. Between the checklist and the frequent calls over Skype and FaceTime, it’s like they never left.

“Nine,” Mom says. Her blond hair is pulled back in her signature French twist and her makeup is perfect, even though it’s barely five a.m. in San Francisco. My parents’ flight home doesn’t take off for another three and a half hours, but Mom is never anything but prepared. “Right after the lighting section.”

“Ah, the lighting section.” My brother, Daniel, sighs dramatically from across the table as he overfills a bowl with Lucky Charms. Daniel, despite being sixteen, has the cereal tastes…

1

Ivy

I respect a good checklist, but I’m beginning to think my mother went overboard.

“Sorry, what page?” I ask, flipping through the handout at our kitchen table while Mom watches me expectantly via Skype. The heading reads Sterling-Shepard 20th-Anniversary Trip: Instructions for Ivy and Daniel, and it’s eleven pages total. Double-sided. My mother planned the first time she and Dad ever left me and my brother alone--for four days--with the same thoroughness and military precision she brings to everything. Between the checklist and the frequent calls over Skype and FaceTime, it’s like they never left.

“Nine,” Mom says. Her blond hair is pulled back in her signature French twist and her makeup is perfect, even though it’s barely five a.m. in San Francisco. My parents’ flight home doesn’t take off for another three and a half hours, but Mom is never anything but prepared. “Right after the lighting section.”

“Ah, the lighting section.” My brother, Daniel, sighs dramatically from across the table as he overfills a bowl with Lucky Charms. Daniel, despite being sixteen, has the cereal tastes of a toddler. “I would have thought we could turn them on when we need them, and off when we don’t. I was wrong. So very, very wrong.”

“A well-lit house deters break-ins,” Mom says, like we don’t live on a street where the closest thing we’ve ever witnessed to a criminal act is kids riding bicycles without a helmet.

I keep my eyeroll to myself, though, because it’s impossible to win an argument against my mother. She teaches applied statistics at MIT, and has up-to-the-minute data for everything. It’s why I’m thumbing through her checklist for the section on CCY Award Ceremony--a list of to-dos in preparation for Mom being named Carlton Citizen of the Year, thanks to her her contributions to a statewide report on opioid abuse.

“Found it,” I say, quickly scanning the page for anything I might have missed. “I picked up your dress from the dry cleaner yesterday, so that’s all set.”

“That’s what I wanted to talk to you about,” Mom says. “Our plane is supposed to land at five-thirty. Theoretically, with the ceremony starting at seven, that’s enough time to come home and change. But I just realized I never told you what to do if we’re running late and need to go straight from the airport to Mackenzie Hall.”

“Um.” I meet her penetrating gaze through my laptop screen. “Couldn’t you just, you know, text me if that happens?”

“I will if I can. But you should probably sign up for flight alerts in case the plane Wi-Fi isn’t working,” Mom says. “We couldn’t get a signal the entire way over. Anyway, if we don’t touch down before six, I’d like you to meet us there and bring the dress. I’ll need shoes and jewelry, too. Do you have a pen handy? I’ll tell you which ones.”

Daniel helps himself to more cereal, and I try to suppress my usual low-simmering resentment of my brother as I hastily scribble notes. Half my life is spent wondering why I have to work twice as hard as Daniel at everything, but in this case, I asked for it. Before my parents left, I insisted on handling every aspect of the award ceremony--mainly because I was afraid that if I didn’t, my mother would realize she’d made a mistake by asking me, not Daniel, to introduce her. My wunderkind brother, who skipped a grade and is currently outshining me in every aspect of our senior year, would have been the logical choice.

Part of me can’t help but think Mom regrets her decision. Especially after yesterday, when my one-and-only claim to school fame was brutally torpedoed.

My stomach rolls as I drop the pen and push my empty cereal bowl away. Mom, ever alert, catches the motion. “Ivy, I’m sorry. I’m keeping you from breakfast, aren’t I?”

“It’s fine. I’m not hungry.”

“You have to eat, though,” she urges. “Have some toast. Or fruit.”

The thought doesn’t appeal even a little. “I can’t.”

Mom’s forehead scrunches in concern. “You’re not getting sick, are you?”

Before I have a chance to reply, Daniel loudly fake-coughs, “Boney.” I glare daggers at him, then glance at Mom on-screen to see if she caught the reference.

Of course she did.

“Oh, honey,” she says, her expression turning sympathetic with a touch of exasperation. “You’re not still thinking about the election, are you?”

“No,” I lie.

The election. Yesterday’s debacle. Where I, Ivy Sterling-Shepard, three-time class president, lost the senior-year election to Brian “Boney” Mahoney. Who ran as a joke. His slogan was literally “Vote for Boney and I’ll leave you alone-y.”

Okay, fine. It’s catchy. But now Boney is class president and really will do nothing, whereas I had all kinds of plans to improve student life at Carlton High. I’d been working with a local farm share on bringing organic options to the salad bar, and with one of the guidance counselors on a mediation program to resolve disputes between students. Not to mention a resource-sharing partnership with the Carlton Library so our school library could offer ebooks and audiobooks along with hard copies. I was even looking into holding a senior class blood drive for Carlton Hospital, despite the fact that I faint at the sight of needles.

But in the end, nobody cared about any of that. So today, at exactly ten a.m., Boney is going to give his presidential victory speech to the senior class. If it’s anything like our debates, it will mostly consist of long, confused pauses between fart jokes.

I’ve been trying to put on a brave face, but it hurts. Student government was my thing. The only activity I’ve ever been better at than Daniel. Well, not better, exactly, since he never bothered to run for anything, but still. It was mine.

Mom gives me a look that says Time for some tough love. It’s one of her most powerful looks, right after Don’t you dare take that tone with me. “Honey, I know how disappointed you are. But you can’t dwell, or you really will make yourself sick.”

“Who’s sick?” My father’s voice booms from someplace in their hotel room. A second later he emerges from the bathroom dressed in travel-ready casual clothes, rubbing his salt-and-pepper hair with a towel. “I hope it’s not you, Samantha. Not with a six-hour flight ahead of us.”

“I’m perfectly fine, James. I’m talking to--”

Dad approaches the desk where Mom is sitting. “Is it Daniel? Daniel, did you pick something up at the club? I heard there was a rash of food poisoning over the weekend.”

“Yeah, but I don’t eat there,” Daniel says. Dad recently got my brother a job at a country club he helped develop in the next town over, and although Daniel is only a busboy, he makes a fortune in tips. Even if he had eaten bad shellfish, he’d probably drag himself into work anyway, if only to keep adding to his collection of overpriced sneakers.

As usual, I’m an afterthought in the Sterling-Shepard household. I half expect my father to inquire about our dachshund, Mila, before he gets to me. “Nobody’s sick,” I say as his face comes into focus over Mom’s shoulder. “I’m just . . . I was wondering if maybe I could go to school a little later today? Like, eleven or so.”

Dad’s brows shoot up in surprise. I haven’t been absent for a single hour of my entire high school career. It’s not that I never get sick. It’s just that I’ve always had to work so hard to stay on top of classes that I live in constant fear of falling behind. The only time I ever willingly missed school was way back in sixth grade, when I spontaneously slipped out of a boring field trip at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society with two boys from my class who, at the time, I didn’t know all that well.

We were seated close to an exit, and at a particularly dull point in the lecture, Cal O’Shea-Wallace started inching toward the auditorium door. Cal was the only kid in our class with two dads, and I’d always secretly wanted to be friends with him because he was funny, had a hyphenated last name like me, and wore brightly patterned shirts that I found oddly mesmerizing. He caught my eye, and then the eye of the kid next to me, Mateo Wojcik, and made a beckoning motion with one hand. Mateo and I exchanged glances, shrugged--Why not?--and followed.

I thought we’d just linger guiltily in the hallway for a minute, but the outdoor exit was right there. When Mateo pushed it open, we stepped into bright sunshine, and a literal parade that happened to be passing by to celebrate a recent Red Sox championship. We melted into the crowd instead of returning to our seats, and spent two hours wandering around Boston on our own. We even made it back to the Horticultural Society without anyone realizing we’d been gone. The whole experience--Cal called it “the Greatest Day Ever”--created a fast friendship between the three of us that, at the time, seemed like it would last forever.

It lasted till eighth grade, which is almost the same in kid years.

“Why eleven o’clock?” Dad’s voice yanks me back into the present as Mom twists in her chair to look at him.

“The post-election assembly is this morning,” she says.

“Ahh,” Dad sighs, his handsome features settling into a sympathetic expression. “Ivy, what happened yesterday is a shame. But it’s no reflection of your worth or ability. That wasn’t the first time a buffoon has been handed an office he doesn’t deserve, and it won’t be the last. All you can do is hold your head high.”

“Absolutely.” Mom nods so vigorously that a strand of hair nearly escapes her French twist. But not quite. It wouldn’t dare. “Besides, I wouldn’t be surprised if Brian ends up resigning when all is said and done. He’s not really cut out for student government, is he? Once the novelty wears off, you can take his place.”

“Sure,” Dad says cheerfully, like being Boney Mahoney’s cleanup crew wouldn’t be a mortifying way to become class president. “And remember, Ivy: anticipation is often worse than reality. I’ll bet today won’t be nearly as bad as you think.” He puts a hand on the back of Mom’s chair and they smile in unison, framed like a photograph within my laptop as they wait for me to agree. They’re the perfect team: Mom cool and analytical, Dad warm and exuberant, and both of them positive that they’re always right.

The problem with my parents is that they’ve never failed at anything. Samantha Sterling and James Shepard have been a power couple ever since they met at Columbia Business School, even though my dad dropped out six months later when he decided he’d rather flip houses. He started here in his hometown of Carlton, a close-in suburb of Boston that turned trendy almost as soon as Dad acquired a couple of run-down old Victorians. Now, twenty years later, he’s one of those recession-proof real estate developers who always manages to buy low and sell high.

Bottom line: neither of them understand what it’s like to need a day off. Or even just a morning.

I can’t bring myself to keep complaining in the face of their combined optimism, though. “I know,” I say, suppressing a sigh. “I was kidding.”

“Good,” Mom says with an approving nod. “And what are you wearing tonight?”

“The dress Aunt Helen sent,” I say, feeling a flicker of enthusiasm return. My mother’s much older sister might be pushing sixty, but she has excellent taste--and lots of discretionary income, thanks to the hundreds of thousands of romance novels she sells every year. Her latest gift is from a Belgian designer I’ve never heard of before, and it’s the most fashionable thing I’ve ever owned. Tonight will be the first time I’ve worn it outside my bedroom.

“What about shoes?”

I don’t own shoes that do the dress justice, but that can’t be helped. Maybe Aunt Helen will come through on those when she sells her next book. “Black heels.”

“Perfect,” Mom says. “Now, in terms of dinner, make sure you don’t wait for us since we’re cutting it so close. You could unfreeze some of the chili, or--”

“I’m going to Olive Garden with Trevor,” Daniel interrupts. “After lacrosse practice.”

Mom frowns. “Are you sure you’ll have time for that?”

That’s my brother’s cue to change his plans, but he doesn’t take it. “Totally.”

Mom looks ready to protest, but Dad raps his knuckles on the desk before she can. “Better sign off, Samantha,” he says. “You still have to pack.”

“Right,” Mom sighs. She hates to rush when it comes to packing, so I think we’re done until she adds, “One last thing, Ivy--do you have your remarks for the ceremony all ready?”

“Yeah, of course.” I’d spent most of the weekend working on them. “I emailed them yesterday, remember?”

“Oh, I know. They’re wonderful. I just meant . . .” For the first time since we started speaking, Mom looks unsure of herself, which almost never happens. “You’re going to bring a hard copy with you, right? I know how you--I know you can get nervous in front of a crowd, sometimes.”

My stomach tightens. “It’s in my backpack.”

“Daniel!” Dad barks suddenly. “Turn the computer, Ivy. I want to talk to your brother.”

“What? Why?” Daniel asks defensively as I spin the laptop, my cheeks starting to burn with remembered humiliation. I know what’s coming.

“Listen, son.” I can’t see Dad anymore, but I can picture him trying to put on his stern face. Despite his best efforts, it’s not even a little bit intimidating. “I need you to promise that you will not, under any circumstances, mess with your sister’s notes.”

“Dad, I wouldn’t-- God.” Daniel slumps in his chair, rolling his eyes exaggeratedly, and it takes everything in me not to throw my cereal bowl at his head. “Can everyone please get over that? It was supposed to be a joke. I didn’t think she’d actually read the damn thing.”

“That’s not a promise,” Dad says. “This is a big night for your mother. And you know how much you upset your sister last time.”

If they keep talking about this, I really will throw up. “Dad, it’s fine,” I say tightly. “It was just a stupid prank. I’m over it.”

“You don’t sound over it,” Dad points out. Correctly.

I turn my laptop back toward me and paste on a smile. “I am, really. It’s old news.”

Based on my father’s dubious expression, he doesn’t believe me. And he shouldn’t. Compared to yesterday’s fresh humiliation, sure--what happened last spring is old news. But I am not, in any way, shape, or form, over it.