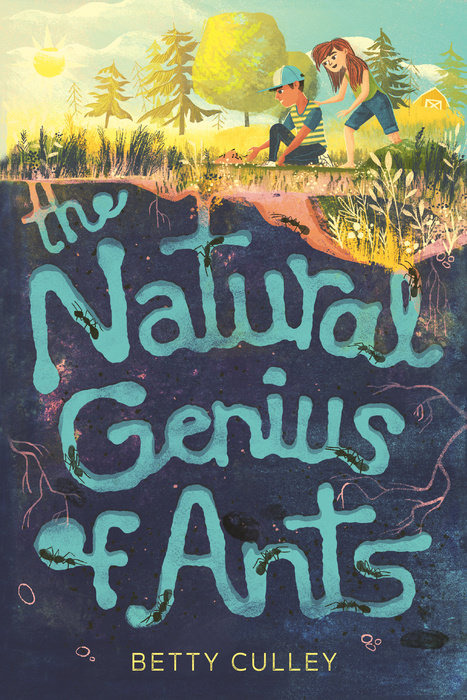

The Natural Genius of Ants

Author Betty Culley

A summer ant farm grows into a learning experience for the entire family in this lyrical coming-of-age story from the award-winning author of Down to Earth.

"Endearingly executed, this gentle tale will see readers applauding as they reach the end.” –Booklist, Starred Review

Harvard is used to his father coming home from the hospital and telling him about all the babies he helped. But since he made the mistake at work, Dad has been quieter than usual.

A summer ant farm grows into a learning experience for the entire family in this lyrical coming-of-age story from the award-winning author of Down to Earth.

"Endearingly executed, this gentle tale will see readers applauding as they reach the end.” –Booklist, Starred Review

Harvard is used to his father coming home from the hospital and telling him about all the babies he helped. But since he made the mistake at work, Dad has been quieter than usual. And now he is taking Harvard and his little brother, Roger, to Kettle Hole, Maine, for the summer. Harvard hopes this trip isn’t another mistake.

In the small town where he grew up, Dad seems more himself. Especially once the family decides to start an ant farm--just like Dad had as a kid! But when the mail-order ants are D.O.A., Harvard doesn't want Dad to experience any more sadness. Luckily, his new friend Neveah has the brilliant idea to use the ants crawling around the kitchen instead. But these insects don't come with directions. So the kids have a lot to learn--about the ants, each other, and how to forgive ourselves when things go wrong.

An Excerpt fromThe Natural Genius of Ants

ONE

The Mistake

Dad said being in Kettle Hole was like going back in time, but I didn’t know what he meant until we got here. The trees are tall and straight, and farm fields stretch out to the sky. There are gigantic bullfrogs with eyes as big as nickels, and trucks filled with logs rumble down the dirt roads, blowing up dust. Instead of streetlights shining outside our windows, we’re in a place so dark at night you feel invisible. A place where you hear coyotes howl and yip. Dad says they live deep in the woods, even though it sounds like they’re very close.

We came here because of my father’s mistake. He can’t forgive himself for what he did. It doesn’t matter that he’s a doctor, and doctors make mistakes like everybody else.

After the baby died, Mom tried to explain why Dad was so sad. She said people are human and she’d gotten things wrong at work, too.

“Did any parasites die?” I asked. She’s studying a parasite that makes people lose their vision. It’s so…

ONE

The Mistake

Dad said being in Kettle Hole was like going back in time, but I didn’t know what he meant until we got here. The trees are tall and straight, and farm fields stretch out to the sky. There are gigantic bullfrogs with eyes as big as nickels, and trucks filled with logs rumble down the dirt roads, blowing up dust. Instead of streetlights shining outside our windows, we’re in a place so dark at night you feel invisible. A place where you hear coyotes howl and yip. Dad says they live deep in the woods, even though it sounds like they’re very close.

We came here because of my father’s mistake. He can’t forgive himself for what he did. It doesn’t matter that he’s a doctor, and doctors make mistakes like everybody else.

After the baby died, Mom tried to explain why Dad was so sad. She said people are human and she’d gotten things wrong at work, too.

“Did any parasites die?” I asked. She’s studying a parasite that makes people lose their vision. It’s so small you can only see it through a special microscope.

My little brother Roger’s eyes got very big.

Since Dad’s mistake, my mouth has been on autopilot.

“Harvard!” Mom said my name once, like a warning, and quickly looked around to see if Dad had heard me. Luckily, he hadn’t.

For five months after his mistake, Dad didn’t work. He didn’t leave our apartment on the fifth floor except to get a haircut. He cried when no one was looking and even when everyone was looking.

Then he got the idea for us to go to Kettle Hole for the summer, the place where he grew up. His childhood friend Vernon Knowles was renting out his house six states away from our apartment and the hospital where Dad used to work.

“You know I can’t leave my research right now,” Mom said when Dad told us about his plan.

“I know you can’t leave the parasites. They need you so much. They depend on you. They can’t live without you,” I said. Mom and I collect parasite jokes.

Later, I overheard Mom and Dad talking in their bedroom. She asked him why he wanted to go to Kettle Hole. In his thought-out, list-making way, he gave her three reasons.

“People know me as the Corson boy there, not Dr. Corson. Kettle Hole is always in my heart, even though I haven’t been back since my grandfather’s funeral. And Robert Frost was right—that home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.”

Mom had one answer to his three reasons.

“If that’s what you need to do, Marshall.”

Dad answered back, “Vern thought Earlene would make it, but she’s been gone six months and he’s in a spot trying to pay off her medical bills and raise his daughter. He was going to lose the house, and we need a place to stay. Give me this time with the boys, Dee. Maybe I can do something right and make it a summer they will always remember.”

It was quiet then, and I peeked into their room. Mom had her arms around Dad, her cheek pressed against his. He just stood there with his arms hanging down, like he didn’t have enough energy to hug her back.

Mom answered, “You were born to be a doctor, Marshall. Please use this summer to figure out a way to forgive yourself.”

To get to Kettle Hole, we drove east for more than a day and then headed north. The highway in Maine was only two lanes, and the farther north we went the less cars there were on the road.

I’ve never been to the town where my father grew up. Mom grew up in the city where we live, but Mom’s mother, my abuela, is from the Dominican Republic. I’ve never been there, either. Part of the year she lives right near us, and part of the year she goes back to the DR to see family.

“The fields and the woods are just how I remember,” Dad said when we got off the highway. “It’s like going back in time.”

“Then you better speed up,” I blurted out.

Dad drove exactly five miles under the speed limit, both hands on the wheel.

“Why would I want to do that?” he asked without turning his head away from the road.

“So we get there before you’re too young to drive. And I’m only ten, so if you go too slow, I’ll disappear.”

I saw a little smile on Dad’s face in the rearview mirror, but he didn’t drive any faster.

Being on a long car trip makes you think about things.

Roger, I know, thought about one thing. The food in the cooler on the back seat between us. He’d watched Dad fill it and he had a contest with himself to eat some of everything packed in there. Grapes, cheese slices, juice boxes, macaroni and cheese, oatmeal raisin cookies.

Mom wouldn’t have let Roger eat so much, but Dad was busy driving. And when Roger had food in his mouth, he wasn’t asking the same thing over and over—What do you think Mommy is doing RIGHT NOW? Or saying, If Mommy was here, she’d sing the car song. I have no idea what the car song is, but Roger sang the only lines he remembered until they were stamped in my brain.

Car, car, car

Far, far, far

While Roger ate, I looked out my window and thought about the things people say about mistakes, all of which are wrong:

Mistakes happen.

Don’t be afraid to make mistakes.

It’s only a mistake.

You learn from your mistakes.

Don’t worry. It was an honest mistake.

None of those things are true, I thought, because if they were, Dad would still be taking care of the smallest and sickest babies in the hospital instead of planning our summer to remember. Roger wouldn’t be one state away from a bellyache after eating his hundredth snack. All I could do, as we got closer and closer to Kettle Hole, was hope that going back to the place where Dad grew up wouldn’t turn out to be another mistake.

TWO

One Word or Two?

When we finally pull up in front of Mr. Knowles’s house in Kettle Hole, it’s dark all around us, with only one light shining on a porch the whole length of the house. Dad shuts off the motor and opens the car door. Roger snores in his sleep.

“Listen,” Dad says. “Barred owls.”

There’s an eerie hooting noise and then cries like monkeys screaming. Dad stands there looking into the woods where the sounds are coming from.

“Do you have the key to the house?” I ask.

“It should be open,” he says.

That’s how I end up being the first one in, carrying my backpack over my shoulder. I feel for a switch on the wall, and the room lights up. The floor is wood and the house smells like the cabin I stayed in at summer camp last year. It’s colder inside the house than outside. The living room has a couch and chair at one end and a desk and floor lamp in a corner. There’s a kitchen with a square table and four chairs. The windows are low and tall, and none of them have curtains.

Up a set of stairs are three bedrooms and a bathroom. One bedroom has a big bed like Mom and Dad’s. I drop my backpack on the bed in the smaller of the other two. This way there’s no tears from Roger for getting the worst room. Plus the smallest room has a window that looks out onto a roof, and a long closet under a sloping wall. That night I fall asleep on the bed in the room without even taking my sneakers off.

The morning after we arrive, I’m the last one awake. Dad is in the kitchen and I smell his coffee brewing. Roger is at the kitchen table.

“What are Roger and I going to do here?” I ask Dad.

“Any number of things,” he says. “See what catches your eye, where your interests take you.”

Dad’s face is pale from spending the past five months inside, his eyelashes almost see-through, and his hair is the same light brown as Roger’s, but thinner on top.

“What about you? What are you going to do?” I ask him.

“I’m going to work on being a better parent,” he says.

“Better how? Who are you competing against?” The words are out before I have a chance to think.

Dad answers in a serious voice.

“Better in all ways, Harvard. More involved. More focused. More adaptable.”

“You’re hired. When can you start?”

Dad ignores or doesn’t notice that I’m being mouthy. He drops toast on plates, puts out jelly, shakes the orange juice container, and spins silverware across the table so it lands exactly in front of where we’re each sitting. Then he sits down and clasps his hands on the table in front of himself.

He’s wearing a white short-sleeved button-down shirt, and in the front pocket there’s a pen and a mini notepad.

“I didn’t bring the computer because there’s no internet connection in the house. It’s also hard for me to get reception on my cell phone unless I’m outside. But anytime you want to call Mom you can use the house phone there on the desk.”

“Is that what you meant by going back in time?” I ask.

“Internet access and TV cost money Vern doesn’t have. I think you’ll find plenty of things to keep you busy here. Also, I want you both to know you can talk to me about anything, and ask whatever questions you have.”

I can’t stop myself. “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?”

“Which came first, the chicken or the egg?” Roger repeats, tipping himself out of his chair and onto the kitchen floor laughing. He’s still holding a piece of jelly toast in one hand.

Roger is five and falls on the floor whenever he thinks something is really funny.

“Roger, back in your chair,” Dad says automatically. “That’s an eternal question, isn’t it? I don’t have an answer. I also wanted you to know you can invite your friends here anytime. If they fly up, we can meet them at the airport.”

There’s only my friend Tobias who I’d want to come. He’s the friend who never asked why Dad was always home or why Dad would sometimes cover his eyes with his hands and turn away. Tobias would sit at the kitchen island while Dad was cooking or cleaning up and tell him stories about what happened at school.

“The word vacationland. Would you think it was one word or two?” I ask.

On the drive here I saw the Maine license plates, white with black letters and the word vacationland on the bottom.

“I don’t know. Probably two?” Dad guesses.

“That’s what I thought, but it was one word on the Maine license plates. Vacationland. Not vacation land. It doesn’t make sense.”

I don’t stop there.

“It’s hard to know, right? Like why is toothbrush one word but swimming pool is two words?”

“Swimming pool. Can we get a swimming pool?” Roger asks.

“And bathroom and spaceship are one word, but ice cream is two words.”

“That is a puzzle,” Dad says, looking at his plate. He cuts the crusts off his toast with a knife and fork, cuts the toast into four squares, then cuts the squares into perfect triangles.

“I want ice cream, too. Swimming pool. Bathroom. Spaceship. Swimming pool. Bathroom. Spaceship. Ice cream,” Roger says over and over, because whatever I say, Roger wants to say at least twice.

Dad puts down his knife and fork. He presses his hand on his throat, over the place where his stethoscope used to hang. When I first started blurting things out, Mom said, If you can, Harvard, before you say something you might regret or that could hurt someone’s feelings, ask yourself why you’re saying it. And if you know the reason and it’s a good reason, then go ahead.

But the sadder Dad is, the more I can’t stop to ask myself anything. Or maybe I don’t try because what if some of those words make him laugh again?

THREE

Heat Lightning

On our first day in Kettle Hole, I see a bullfrog and a skinny snake with yellow stripes in the woods, and get bitten by bugs Dad calls deerflies. Roger plays ball with Dad, climbs in the tire swing that’s hanging from a tree, and rocks himself in a hammock on the back lawn.

Dad says Vernon Knowles and his daughter are supposed to stop by around dark. I’m near the open window when a man and a girl walk up the stone step onto the porch. The sun hangs right over the tops of the trees, and the sky is orange and pink.

The porch light shines on them. The man is wearing a T-shirt and jeans.

“I don’t think I’ve ever knocked on this door before,” he says.

The girl leans against him. He puts his arm around her. The girl’s face reminds me of a bird. It’s triangle-shaped, with her chin the bottom point and her brown eyes far apart above a small sharp nose. Her brown hair hangs down past her shoulders.

“Me neither,” she says.

“They’re here,” I call to Dad, “but they’re just standing there on the porch.”

Dad rushes to the door and opens it wide. The man comes in first. He’s shorter than Dad and his arms are thick and muscly, like a weight lifter’s. His hair is almost as dark as mine and Mom’s.

Dad hugs the man, who thumps him on the back.

“Marshall Corson, Spelling Bee King of Kettle Hole,” his friend says. “Welcome back!”

“Vern,” Dad says. “It’s been too long.”

Mr. Knowles squeezes Dad’s shoulder.

“Thank you, Marshall, for helping me keep my promise to Earlene and stopping us from losing the house. I’m sure my father is looking down on me, shaking his fist that I took out a second mortgage on the homestead.”

“No, it’s you, Vern, who helped me, more than you know. Boys,” Dad says, “meet Mr. Knowles, my oldest friend in the world. Vern, this is my son Harvard, and that’s my younger boy, Roger.” Dad points first to me, still near the window, and then to Roger, who’s on the couch. Roger waves at them with both hands.

“Hello there, Roger!” Mr. Knowles waves back, then turns to me. “Harvard, that’s a great old Maine name. I hope it suits you as well as it did your great-grandfather. He was a good man. And this is my daughter, Nevaeh. She’ll be eleven in October.”