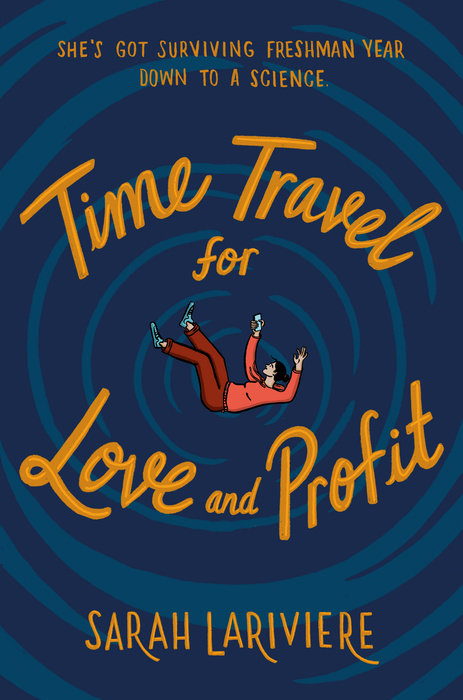

Time Travel for Love and Profit

When Nephele has a terrible freshman year, she does the only logical thing for a math prodigy like herself: she invents a time travel app so she can go back and do it again (and again, and again) in this funny love story, Groundhog Day for the iPhone generation.

Fourteen-year-old Nephele used to have friends. Well, she had a friend. That friend made the adjustment to high school easily, leaving Nephele behind in the process. And as Nephele looks ahead, all she can see is three very lonely years.

Nephele is also a whip-smart lover of math and science, so she makes a plan. Step one: invent time travel. Step two: go back in time, have a do-over of 9th grade, crack the code on making friends and become beloved and popular.

Does it work? Sort of. Nephele does travel through time, but not the way she planned--she's created a time loop, and she's the only one looping. And she keeps looping, for ten years, always alone. Now, facing ninth grade for the tenth time, Nephele knows what to expect. Or so she thinks. She didn't anticipate that her new teacher would be a boy from her long ago ninth grade class, now a grown man; that she would finally make a new friend, after ten years. And, she couldn't have pictured someone like Jazz, with his deep violet eyes, goofy magic tricks and the quietly intense way he sees her. After ten freshman years, she still has a lot more to learn. But now that she's finally figured out how to go back, has she found something worth staying for?

An Excerpt fromTime Travel for Love and Profit

Chapter 1

My Miserable Destiny

The day my best friend, Vera Knight, dumped me, I didn’t know what happened. We were sitting in the cafeteria right after winter break. I was eating my usual burrito. Vera was eating her usual six jelly beans and a bagel. I said, “My current favorite mathematical concept is fractals. Not only do they make psychedelic patterns, they also describe infinity.”

Vera nodded, and nudged a white jelly bean across the table with her index finger.

“What’s your current favorite mathematical concept?” I asked. “You’re probably still obsessed with square roots.”

Vera kept nodding and looked over her shoulder. I looked where she was looking and saw nothing but Ramsey Schultz, with her bored facial expression and her multitude of extraneous accessories. The dangly feather earrings, the metallic boots, the table of worshippers who shadowed her every move like spy drones.

“Square roots,” I said. “I knew it.”

Vera stood, said “I’ll be right back,” walked to Ramsey’s table, sat, and didn’t say another word to me for the rest of the year.

Of course, at the time, I didn’t know Vera was ghosting me. Sure, I knew that Vera and Ramsey had been taking ballet together, and that Ramsey, according to Vera, was “actually supersweet.” But Vera said she’d be right back, and I believed her. So I enjoyed the remainder of my burrito, ignorant of my miserable destiny. The icy shivers I would get when Vera passed me in the hallways and looked through me like I was transparent. The dizziness that would hit when I realized she was never going to answer my texts. The misery of overhearing my peers describe a party at Vera’s house, during which there was a kissing game, where actual kissing happened. Vera and I had sworn we’d tell each other every single detail of our first kisses. Did Vera kiss someone? Who was it? How was it? The loneliness of knowing she’d never tell me.

Things only got worse from there. When I walked down the hallway, Ramsey and her minions hissed. I guess they were supposed to be snakes, and I was the prey or something? Whatever it was, it worked; I felt like a moving target. Other kids pretended not to see me, as if looking at me might get them sent to Outcast Island, too. Then one day, someone shouted, “Neffa-Freak!” And the insult caught on. Perhaps because it’s easier to pronounce than my name, which is Nephele, after a cloud nymph from Greek mythology who is so obscure I was pretty sure nobody but my mother had ever heard of her. NEH-fuh-lee rhymes with especially is what Mom used to tell me to tell people, but you’d have to be alarmingly adorable to pull that off. Alarming I could do. Adorable? Not so much.

And then there was Valentine’s Day. Oh, how I loved Valentine’s Day. The one holiday a year when a dashing stranger might parachute into Redwood Cove out of nowhere, march up to me with a rose between his teeth, and kneel, holding a sign above his head that said, Nephele, your beauty may be complicated, but it is unmistakable, while a chubby baby with hot-pink cheeks shot an arrow made of sunbeams through my heart. I was sitting on the redwood stump outside the school, imagining other things my valentine might proclaim, such as Nephele, let’s go to the beach together and contemplate irregular polyhedrons until the sun plunges into the deep blue sea, when Youki Johnson fist-bumped Kyle “Dirty Dog” Jones and started walking my way.

Youki had the face of a superhero, and he was a straight-A student like me. And he was coming to talk to me—on Valentine’s Day. My head hummed. My tongue tingled. I was so excited that I almost forgot how to breathe. Looking back, my reaction was irrational, but at the time, I couldn’t think straight. I’d been fantasizing about a moment like this for years.

When Youki stopped in front of me, he handed me a pink razor tied with a droopy red bow. “This is for you, Woolly Mammoth,” he said. “Shave those hairy arms.”

Kyle fell all over himself laughing in this strangled way, like he was choking on a chipmunk. Other kids also laughed. A few frowned; a few looked at their feet.

I looked at the pink razor dressed up in its bow tie and wondered where Youki had gotten the red ribbon. Did his mother keep a roll of it for presents? Had he asked her for a piece of it that morning? Had she smiled when she’d handed it to him, proud that her son had found a valentine?

Then I looked at my arms. Thousands of thick black hairs crawled over each other like headless, skinny, wiry blind worms. I was hairy. My mother was hairy. Our relatives in Greece were total furballs. Our hairiness was fascinating, and I knew this. I wished someone would explain the rules to me about what constituted an attractive person and what did not. It made zero sense, mathematically.

“Omigod, she’s talking to herself,” said someone, and I looked up. Behind Youki, Ramsey was wiping tears of laughter from her eyes. She said, “That girl is, like, aggressively weird.”

Beside Ramsey, Vera was frowning, playing with a droopy branch of a cypress tree. “It’s not her fault,” she said. My ears perked up, and my heart pumped a woozy, hopeful beat. Was my former best friend finally going to defend me?

Vera went on. “My mother says all prodigies develop abnormal personalities after puberty.”

I closed my eyes and concentrated on the black static pattern of the galaxy. Inner space. I liked inner space. It was safe in there.

After Valentine’s Day came spring, with its bursts of rain, and its dewy flowers, and its rapidly multiplying bunnies—and a rapidly multiplying crowd of people who yelled, “Neffa-Freak!” when I walked by. I felt more and more lonely and desperate, like the world would just keep turning while I spiraled down a rickety roller coaster that was one earthquake away from collapsing.

When the last day of freshman year was finally over, I walked directly to the Big Blue Wave. My loose plan was to hide in my parents’ bookshop until I died of a rare used-book disease, such as paper-cut plague or word poisoning.

The foghorns moaned low and steady as I crossed Highway 1 and turned onto Main Street. The wind was tugging my hair out of its bun and tying it in knots. I put up my hood and shoved my hands deep in my sweatshirt pockets.

The Big Blue Wave used to be a fish-canning factory. It’s brick with tons of windows and two floors crammed with used books, with a special section on California History for the tourists. Sometimes birds slip in through the skylights and flit around, pooping on the cement floor. The front door was propped open, and from Main Street I heard Dad spinning jazz saxophone.

My parents are tragically analog. Fact: One milk crate full of records weighs as much as a baby sperm whale. Dad has more than a hundred crates, and he keeps the bulk of his collection in the shop. I’m always offering to digitize it. I think I do it just to see the face Dad makes when I use the word “digitize.” It’s disturbing.

Dad was standing behind the checkout counter, wearing his usual outfit of a band T-shirt, a flannel button-down and jeans. Recently he’d grown a mustache. It was puffy and red, as opposed to his hair, which was curly and black, which created a clashing situation that Mom and I couldn’t decide how we felt about.

When he saw me, he called, “Congrats, Fi! Another year bites the dust.”

My parents were the only ones who called me “Fi.” It’s pronounced “fee,” as in when you have to pay extra.

I leaned on the counter. “Well, it bites, anyway.”

“It’s like that?” said Dad. “What’s up?”

I sighed. I didn’t know what to tell him. That I’m destined to spend eternity alone? Dad would only try to reassure me. Ignore the haters, this too shall pass, get that dirt off your shoulder, etc.

“Where’s Mom?” I asked.

“She’s in the back, whittling.”

My mother was in a whittling phase. “Spatula?” I asked.

“Spoon,” said Dad. “Maybe this’ll cheer you up. Came in today.”

Dad handed me a hardback book with a glossy cream cover that was torn around the edges. The title was written in faded purple calligraphy: Time Travel for Love & Profit. That was it; just text. No illustrations of futuristic vehicles, no calendar with the dates swirling in a tornado. No Civil War soldiers dancing in a 1970s New York City disco. No half-naked alien draped over a cowboy with perfect teeth. Oh well. It would probably be pretty good, anyway. I turned the book over and read the back cover out loud. “The author, Oona Gold, lives in the beautiful cosmos.”

Dad said, “If it gets your stamp of approval, would you mind shelving it?”

“Sure, boss,” I said as Dad saluted me and turned to help a customer.