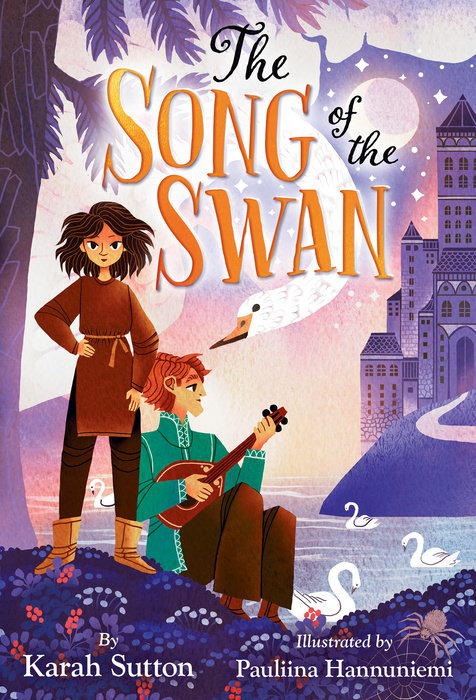

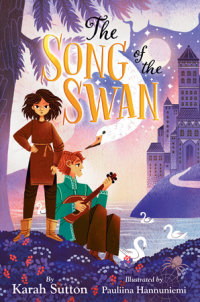

The Song of the Swan

A magical retelling of Swan Lake, featuring a clever orphan, a castle filled with enchanted swans, and a quest to unearth the secrets of the past.

Olga is an orphan and a thief, relying on trickery and sleight of hand to make her way in the world. But it’s magic, not thievery, that could get her into trouble.

When Olga and her partner-in-crime Pavel learn of a valuable jewel kept in a secluded castle, Olga sees an opportunity to change their lives: a prize so big, they’d never have to steal again. But the castle is not as it seems, ruled by an enchanter who hosts grand balls every night, only for the guests to disappear each morning, replaced by swans. Guided by cryptic clues from the palace spiders, Olga soon realizes she’s in over her head—torn between a bargain with the enchanter, loyalty to Pavel, and determination to understand how the enchanted swans are linked to her own fate.

One thing is certain: there is dark magic behind the castle’s mysteries, and Olga will stop at nothing to unmask it.

An Excerpt fromThe Song of the Swan

one

Years of traveling with a notorious swindler had taught Olga an important lesson: people who are trusting are the easiest to trick.

So she ignored the obvious lies being spun by her deceitful guardian as she jabbed her needle into the sewing in her lap.

“My illustrious lady!” shouted Mr. Bulgakov at a passing woman. “Don’t be shy. Your beauty needs no decoration, but our fine jewelry will complement the sparkle of your eyes.”

Mr. Bulgakov gave his usual speeches to the visitors of the market, but so far no one had been drawn in. Other merchants were beginning to disassemble their stalls, and very few stragglers meandered past, those who did only half listening to Mr. Bulgakov’s entreaties. “Jewelry, fine fabric, delicate trinkets, and music boxes! We have sold to tsars and kings and sultans, so exquisite are our wares!”

Behind the wagon, which had fabric draped over it to form the tent of their stall, Olga stayed hidden. She wasn’t good at interacting with customers. She yanked the thread, groaning as she made yet another messy stitch that her magic could not quite hide.

There was a rustle of fabric, and Mr. Bulgakov peeked around the tent to glare at her. “This is your fault. They can see through your magic—they know that the merchandise is shoddy.” His cheeks were red beneath his beard from the heat of the day. Dust from the road flecked the brim of his cap.

Olga bit back the temptation to tell him that he could lie a little less extravagantly, but that was a criticism he would not receive well. And his critique of her magic was accurate— her crudely knotted heartstring around the tin necklaces and threadbare fabrics could fool only one person in ten. Most people could discern that something wasn’t right, even if they couldn’t tell that magic was involved.

“Psst, Olga, what do you think?”

She turned to find Pavel admiring himself in a mirror at the stall next to theirs, sporting an embroidered tunic and outrageous hat. The tunic looked well made, and the fabric hung elegantly on Pavel’s hulking form, but: “The hat’s too small for your big head,” she hissed.

“You’re right,” Pavel whispered, swapping out the first hat for another, this time with a ridiculous feather.

“That’s a ladies’ hat,” she said, trying to focus on her own stitching.

“I still think it suits me,” said Pavel. He turned back to the mirror and stroked the feather on this new hat, flicking his bushy red eyebrows up and down and wrinkling his nose. He was a good five years older than Olga—nearly eighteen—but sometimes he acted like a younger brother.

Her stomach rumbled. She would need to learn how to prepare better illusions if she wanted to avoid going hungry so often. The meager stash of coins from their last sale was already running low.

Mr. Bulgakov claimed that one day their trickery would yield a sum so grand that they would never go hungry again, but in the meantime a life of swindling was their only choice.

And now he would demand that Olga steal food, since they hadn’t managed to sell anything at the market.

Olga looked once more at her embroidery, wishing the lumpy birds and malformed roses were beautiful enough that she could sell her work without resorting to illusion. She gave Pavel a sidelong glance. “Looks like I’ll need to find some supper for the evening.”

Pavel returned the hat and cloak and ducked back into their tent, his full height knocking the canvas from the wagon so it fluttered down. The sounds of Mr. Bulgakov grumbling were crystal clear without that cloth barrier. Pavel gave the old man a smile and stooped to set everything right again with a quick “Sorry!” Pavel was always forgetting how tall he was.

“Don’t bother,” said Mr. Bulgakov. “We might as well pack everything away anyway. Olga, find us some food before it’s all gone—”

“I’m going, I’m going,” Olga muttered. She was already a few paces away from their wagon, venturing out into the half-shuttered market.

With practiced fingers, Olga swiped what she could from the final few stalls: old potatoes, a couple of apples. She reached to her chest and withdrew a short length of her heartstring—the magic glimmering in a way that only she could see—and used it to lasso a bit of cheese off a table and into her waiting hand.

When she returned to their wagon, Mr. Bulgakov wrinkled his nose.

“That’s the best you could do?” he said. “That won’t last us one meal, let alone to the next village.”

Olga bristled. She hated it when Mr. Bulgakov made her feel like a disappointment. “What would you have done?” she snapped.

“That stall is selling meat pies,” he said, gesturing to a table balanced at the end of a rickety cart. “Bring us one of those.”

Olga took a step toward the stall, then hesitated. At the front of the stall, two children younger than her were playing a chasing game of some sort. They giggled and shrieked with laughter. Their shoeless feet slipped on loose stones, and their clothes had bare patches and threads unraveling at the hems. It was one thing to swindle people who could afford the fake jewelry they sold, or to steal an apple that was no better than pig food, but stealing a whole pie from a struggling family felt different.

Sensing her reluctance, Mr. Bulgakov waved the young children over. “You there! Do you want to see something wondrous?” he said.

The boy, who looked to be the older of the two, stopped chasing his sister when Mr. Bulgakov called. The sister ducked behind him, peering under her brother’s arm at the strangers. Mr. Bulgakov had timed his greeting well: The parents were in the midst of packing away their cart and had disappeared behind it. There was no one to usher the children away.

“I see you have a few pies remaining,” Mr. Bulgakov observed, confident that the children were still listening. “We can trade.”

Olga was about to ask what on earth he planned to tempt these children with when he reached under their cart to withdraw a small music box.

A sharp laugh nearly choked her. The music box ruse was a trick to swindle wealthy aristocrats with more money than sense. Olga would use her magic to craft an illusion that the figure inside the box could move on its own, like a puppet without strings. But these kids were from a working family, the kind that prized every loaf baked, every pail of milk from their goats. The cracked boards on the family’s cart and the threadbare patches on their clothes made this obvious. What on earth would they do with a music box?

Still, the children crept close, and Mr. Bulgakov gave Olga a meaningful look as he opened the music box, leaning forward so that the little girl was afforded a clear view of the sculpted dancer spinning inside.

When Olga didn’t move, Mr. Bulgakov gave her a sharp jab with his elbow, then cleared his throat.

Olga’s insides twisted. The elbow meant that he wanted her to perform magic. She could bewitch the box to make it something these kids couldn’t refuse, and they were unlikely to see through her illusions. But the thought made unease bubble inside her.

“These are usually sold for a silver coin,” Mr. Bulgakov said to the children, pausing to let the boy’s eyes light up at the mention of so much money. “You could sell this at the next market and get much more for it, I am certain.”

Beside her, Pavel tensed. “I thought we only took from people what they can stand to lose,” he said in a low whisper.

“We take from people whose need is less than ours! They are not starving!” Mr. Bulgakov snapped in a voice pitched so only Olga and Pavel could hear. To Olga’s surprise, his expression shifted to one of pleading.

Olga closed her eyes, wanting to ignore him, to walk away from these children and their remaining pies. But she didn’t.

After her mother’s death, Olga had tried to find out about her father but been able to learn nothing other than that he was born somewhere in the Kamen Mountains. With no other relatives to care for her, Olga needed Mr. Bulgakov’s reliance on her magic to give her a home. Even if that home was only the cart they used to get from village to village.

So she tugged a small strand of magic from her chest and reached out to take the music box from Mr. Bulgakov, acting as though she intended to demonstrate how it worked. With shaking fingers, she looped the strand of magic around the dancer, wrapping the tiny sculpture in an illusion that made her dance more lifelike than any wooden carving could be. The eyes of the children widened in wonder as they watched the dancer twist and twirl, finishing at last with a low curtsy.

The girl was itching to touch it. She’d emerged from behind her brother, her fingers twitching. She bit her lip. Her brother reached down and gave her hand a squeeze, then nodded, smiling. The girl squealed with glee, then in a burst of speed turned and ran back to their cart, returning a moment later with a pie on outstretched hands. She nearly tripped in her haste, her bare feet managing to quickly recover on the uneven cobbles, and she clutched the pie close as a newly hatched duckling.