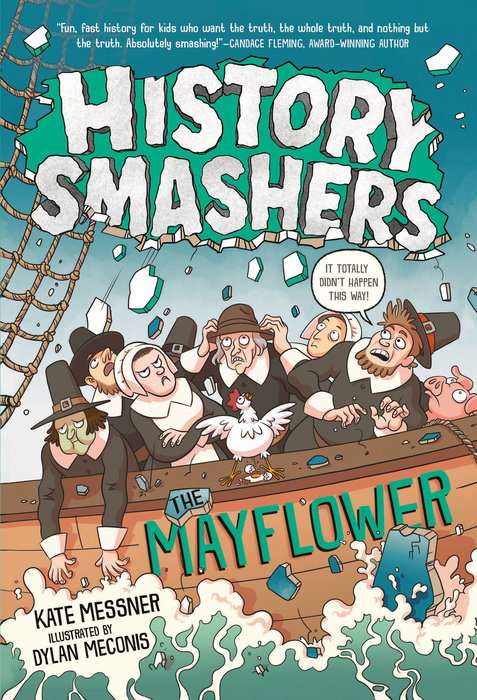

History Smashers: The Mayflower

History Smashers: The Mayflower is a part of the History Smashers collection.

Myths! Lies! Secrets! Smash the stories behind famous moments in history and expose the hidden truth. Perfect for fans of I Survived and Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales.

In 1620, the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock and made friends with Wampanoag people who gave them corn. RIGHT?

WRONG! It was months before the Pilgrims met any Wampanoag people, and nobody gave anybody corn that day.

Did you know that the pilgrims didn't go straight from England to Plymouth? No, they made a stop along the way--and almost stayed forever! Did you know there was a second ship, called the Speedwell, that was too leaky to make the trip? No joke. And just wait until you learn the truth about Plymouth Rock.

Through illustrations, graphic panels, photographs, sidebars, and more, acclaimed author Kate Messner smashes history by exploring the little-known details behind the legends of the Mayflower and the first Thanksgiving.

"Kate Messner serves up fun, fast history for kids who want the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Absolutely smashing!" --Candace Fleming, award-winning author

Don't miss History Smashers: Women's Right to Vote!

An Excerpt fromHistory Smashers: The Mayflower

one

Who Were the Pilgrims, Anyway?

If April showers bring May flowers, what do May flowers bring?

The answer to the riddle, of course, is Pilgrims. The joke works because almost everyone knows a little about the Pilgrims. We’ve heard how they left England and came to America in search of religious freedom. But that’s not even close to the whole story. For starters, the Pilgrims didn’t go to America when they left England. Not at first, anyway.

The real-deal story of the Mayflower begins way back in the 1530s, when King Henry VIII made some big changes to religion in England. King Henry wanted a son who could grow up to be the king of England, too. He and his first wife only had a daughter, though. Henry decided the solution was to get divorced and marry someone else, with whom he might have a son.

But the Roman Catholic Church was the official church in England then, and it did not allow divorce. King Henry went all the way to the pope, the leader of the whole Catholic Church, to argue that he should be able to leave his wife and marry a new one. When the pope said no, Henry decided to break away from the Catholic Church and start his own. From then on, the Church of England would be the official church of the land.

King Henry wasn’t the only one who had issues with the Roman Catholic Church at that time. Many complained that Catholic leaders had too much power and wealth. But not everyone liked King Henry’s new church, either. Some thought it was too similar to the Catholic Church. One group, called the Puritans, wanted the new church to be “purified” of all the old practices. Other people didn’t think that was enough. They were called Separatists because they wanted to separate from the Church of England completely and have their own religion. The Separatists thought that true Christian believers should come together in their own small churches. They wanted those churches to be independent so members could study the Bible and make decisions on their own.

William Brewster, who was the postmaster of a village called Scrooby, decided to start a church in his own house. It was a risky idea. Back then, people who didn’t follow the Church of England could be thrown in jail. In his book Of Plymouth Plantation, Pilgrim William Bradford wrote that Brewster’s Separatists were “hunted and persecuted on every side.”

Government officials were watching the Separatists’ houses day and night. Some of them did get thrown in jail. You can probably understand why leaving England was starting to seem like a good idea.

So that’s when the Separatists set sail for America, right?

Wrong. They went to Holland.

Holland, which today we call the Netherlands, was known for religious freedom. Brewster learned that a small group of Separatists had recently escaped to the city of Amsterdam, where they could practice their religion in peace. That seemed like a good idea, so Brewster made plans to take his group there, too. His followers were nervous, though. They didn’t speak Dutch. They weren’t sure how they’d earn money to support their families. Bradford later wrote that to many of the Separatists, taking off for Holland seemed like “an adventure almost desperate” and “a misery worse than death.” But after much discussion, they decided to go anyway.

1607: Brewster arranged for a ship to sneak his congregation away to Amsterdam. It was expensive, and they had to wait a long time, but he didn’t see any other option.

Finally the day arrived.

It was time for the Separatists to leave England once and for all!

But then everything fell apart.

The ship’s captain had ratted them out!

The ship’s crew ransacked all the passengers’ belongings, looking for money.

They turned the Separatists over to the authorities.

Instead of escaping to Holland,

they ended up spending a month in an English prison.

But Brewster didn’t give up. About a year later, he took his group north in England and found another ship. Officials discovered their plan and tried to catch them again. But this time the Separatists saw the authorities coming. Most of the men had boarded the ship, and in a panic they brought up the anchor, hoisted the sails, and took off. The women and children, who hadn’t boarded yet, were still waiting on the dock with most of their belongings.

English authorities caught the women and children. But then they weren’t quite sure what to do with them, since their husbands and fathers were gone. Eventually, the women and children were released and met up with the others in Holland. This group of Sepa-ratists lived in Amsterdam for about a year before deciding the busy port city wasn’t the right place for them to settle. It was time to move on.

So that’s when they left for Plymouth Rock, right?

Nope. Instead, they moved to another city in Holland, called Leiden.

Leiden was a beautiful city with a university. It was also known for cloth making, and some of the newly arrived Separatists got jobs in that industry. They worked long hours at looms to weave linen and wool cloth. They would bring their products to the town chapel, where members of the local weavers’ guild would examine them. If the cloth was judged to be of high-enough quality, then it could be sold.

Leiden was also home to a towering twelfth-century castle whose grounds had been turned into a public park. When Bradford and the other Separatists weren’t working, they spent time there with their families.

Sounds pretty nice, doesn’t it? But the Separatists weren’t very happy in Leiden, either. The language sounded strange to them, and they weren’t used to the Dutch customs.

Like Amsterdam, Leiden was a busy, bustling city. Too busy and bustling for many of the Separatists. They did their best to make a life there, but it never felt like home. Back in England, many of them had been farmers. They missed the countryside, and their farming skills didn’t transfer well to such a big city. Some had trouble earning money. They were also worried that war might break out between Holland and Spain. And as the years passed, they grew more and more concerned that their English children were becoming Dutch. Some of the older kids had even run off to be soldiers or sailors.

The Separatists had wanted to break away from the Church of England, but they’d never meant to give up being English. There had to be a place where they could raise their families with the old English ways while practicing their religion in peace. So after about twelve years in Holland, they decided that the time had come to move again, to a place they could truly call home.

We’re talking about Plymouth now, right? Actually, no. Not yet.

When the Separatists decided to leave Holland, they weren’t sure at first where they’d go. For a while, they were thinking about Guiana, on the northeast coast of South America. The Dutch had set up a colony there. It was lush and green, with warm weather that made it easy to grow food.

That sounds way better than the freezing-cold winters of New England, doesn’t it? But the Separat- ists worried that the warm weather “would not agree so well with our English bodies.” They feared that diseases would spread easily in the hot climate.

Another option was to cross the ocean but go farther north. There, they’d be living close to other English people. They worried about that, too. What if they were persecuted? What if it felt like England all over again? They’d have gone so far, all for nothing. What should they do?

It wasn’t an easy decision. But in the end, William Brewster and his congregation made plans to say goodbye to Holland and set sail across the Atlantic.

How do we know what we know about the Pilgrims?

How can historians piece together the story of something that happened four hundred years ago? William Bradford, who became the governor of Plymouth Colony, included some details about life in Leiden in his writings. And when the Pilgrims took off from Leiden in 1620, they left behind other clues, too.

Some of the buildings that were part of the Pilgrims’ lives in Leiden are still there, including the old castle Burcht van Leiden and the chapel that also served as the guildhall, where the weavers had their cloth inspected.

A fourteenth-century house that William Brewster supposedly visited while he was in Leiden is a museum now.

The Leiden American Pilgrim Museum displays artifacts from the years the Pilgrims spent in Leiden. Those everyday objects tell stories about daily life. Fragments of pipes and pottery dishes help historians piece together bits of the Separatists’ days in Leiden. There’s a lice comb from the 1500s--evidence that traveling packed together on ships and living in close quarters probably left the Pilgrims with itchy scalps. There are also toy soldiers and jacks. These suggest that play was an important part of the children’s lives and that Pilgrim parents might not have been as stern and strict as we sometimes think.

As for the Pilgrims’ lives in America, along with artifacts, we also have a couple of detailed primary sources to tell that story. A primary source is a firsthand account of something that happened, written by someone who was directly involved in it. Historians generally consider primary sources to be the most valuable references for understanding history.

Still, it’s important to remember that historical writers had their own motivations and biases, just as people do today. And like mod-ern people, seventeenth-century writers didn’t know everything, so some of their writings include misunderstandings or assumptions that are just plain wrong. Really, a primary source isn’t necessarily the truth of what happened; it’s an account of what the writer noticed and believed at that time. And sometimes people lie in primary sources, too, sharing what they want others to believe instead of telling the whole truth.

One of the primary sources about the settlement of Plymouth, Mourt’s Relation, is a collection of letters, documents, and journal entries mostly written by William Bradford and another Pilgrim settler, Edward Winslow, in 1620 and 1621.

The other main primary source about Plymouth is a book called Of Plymouth Plantation, which Bradford started writing in 1630. It’s interesting to compare the two sources.

Wait . . . was it “Plymouth” or “Plimoth”?

In documents about this colony, you’ll find its name spelled two different ways--“Plymouth” and “Plimoth.” That’s because back then, there was no standard spelling. William Bradford used the spelling “Plimoth” in his original history, so the living-history museum Plimoth Plantation chose to spell its name the same way. The modern city of Plymouth, Massachusetts, uses the other spelling.

Mourt’s Relation was written close to the time the events were taking place, and parts of it are very detailed. That makes sense if you think about it. What do you remember more vividly--something that happened just last week, or something that happened five years ago? Of Plymouth Plantation was written almost a decade later, so it’s what historians call a “recollection” of events, in which the writer does their best to remember what things were like.

Bradford’s recollection still stands as one of the few accounts of Plymouth written by someone who experienced it--and it was almost lost to us! For generations, Bradford’s writings had been passed down among his descendants. Eventually, Of Plymouth Plantation ended up in the library of Boston’s Old South Church.

The British occupied Boston during the Revolutionary War, and when the war ended, Bradford’s manuscript was missing. It turned up years later in the library of the bishop of London and was printed there in 1856 and brought back to America in 1897.

Did Pilgrims really look like that?

Chances are, you’ve seen pictures of Pilgrims dressed all in black, with fancy buckles on their hats. Maybe when you were in preschool or kindergarten, you even made a hat like that out of construction paper and aluminum foil and wore it for your classroom’s Thanksgiving celebration. But most of the time, Pilgrims didn’t dress like that at all.

This is a situation where mythology--the stories told about a group of people--was accepted as history without proof. Often, modern people think of Pilgrims as being super strict and stern and dressing all in black. There are portraits of Pilgrims dressed in black, like the one of Edward Winslow on the next page. It’s the only portrait of a Pilgrim painted from life, with the subject sitting there while the artist painted, and Winslow is indeed wearing black. But that’s probably because people wore their best clothes to have their portraits made, and in the time of the Pilgrims, most people’s best clothes were black.

Paintings like this one make it easy for people to assume that Pilgrims walked around in black clothes all the time. But historical documents tell a different story.

An estate inventory is a listing of a person’s possessions. It includes all the things they owned at the time of their death. If that myth about Pilgrims wearing all black were true, you’d expect the estate listings from Plymouth Colony to be a long list of black pants and coats. But instead those documents list articles of clothing in all kinds of bright colors--red, yellow, orange, green, and violet, in addition to brown and black.

So when we look at historical documents, we see that the Pilgrims’ world was probably a lot more colorful than many people thought.

two

Voyage on the Mayflower (but Not the Speedwell)

You might think this is the part of the story where the Pilgrims board the Mayflower, cross the ocean, land in Plymouth, and live happily ever after. But the real deal was more complicated than that.

For starters, the Pilgrims couldn’t go anywhere until they figured out how to pay for the trip. It would be expensive. They didn’t need just a ship. They needed enough supplies to last through the journey and their early days in the new colony. Brewster and his Separat- ists didn’t have that kind of money. They needed to make a deal.

The Virginia Company had already sent people to set up a colony in Jamestown and was making plans for another settlement, farther north. That’s where the Pilgrims came into the picture.

The Virginia Company gave them a patent--a document giving them permission to settle in Virginia. It’s worth noting that their “permission” came from the king of England, who’d never set foot in Virginia. What made him think he had the right to give away land on a continent he’d never even visited?

The answer to that question has to do with a set of laws called the Doctrine of Discovery. It was based on a 1452 decree from the pope.