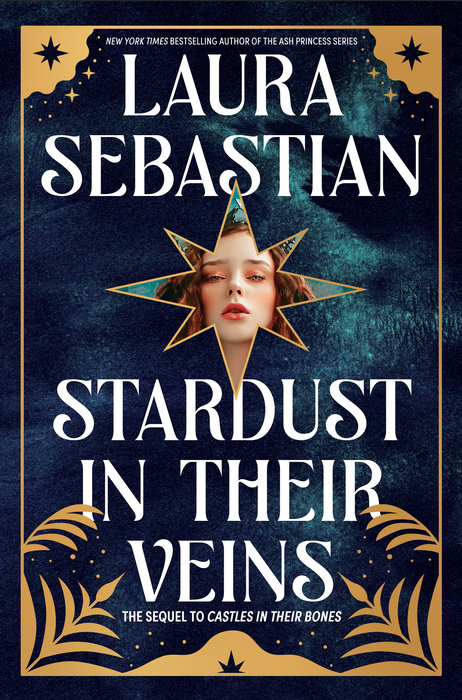

Stardust in Their Veins

Stardust in Their Veins is a part of the Castles in Their Bones collection.

Immerse yourself in the second book in a fantasy trilogy from the New York Times bestselling author of the Ash Pricess series. The sequel to Castles in Their Bones is the story of three princesses and the destiny they were born for: seduction, conquest, and the crown.

Princesses Daphne, Beatriz, and Sophronia have trained their entire lives for one purpose: to bring down nations. Their mother, Empress Margaraux of Bessemia, is determined to rule the continent of Vesteria, and her daughters are her weapons. Promised for marriage since birth, they are her ticket across enemy lines. And also her decoys.

Still, not even Empress Margaraux can control the stars. Sent to their new kingdoms, orders in hand, the princesses have found their own paths, changing the course of their mother’s plans entirely—and tragically. Sophronia chose love, and for that, she lost her life.

Daphne and Beatriz can hardly believe their sister is dead, but both are determined to avenge her. And now, separated by a continent—and their mother’s lies—they see more clearly with every passing day that they might not be working toward the same end.

The stars whisper of death, but Daphne and Beatriz are just beginning to understand the true power coursing through their veins. And their mother will do anything to keep them under her thumb—even if it means killing them all.

An Excerpt fromStardust in Their Veins

Beatriz

Beatriz paces her cell at the Cellarian Sororia nestled in the Alder Mountains, ten steps from wall to wall. It has been five days since she was brought here, sealed away in this sparse chamber with only a narrow bed, a threadbare blanket, and a pitcher of water set on a small wooden stool. It has been five days since she heard her sisters’ voices in her head, as clearly as if they were standing in the room beside her. Five days since she heard Sophronia die.

No. No, she doesn’t know that, not really. There were a dozen explanations for it, a dozen ways Beatriz could make herself believe that her sister was still out there, still alive. Whenever Beatriz closes her eyes, she sees Sophronia. In the silence of her room, she hears her laughter. Whenever she manages to sleep for a few hours, her nightmares are haunted by the last words she spoke.

They’re cheering for my execution. . . . There is so much more at play than we realized. I still don’t understand all of it, but please be careful. I love you both so much. I love you all the way to the stars. And I—

And that had been all.

Beatriz doesn’t understand the magic that made the communication possible—that was Daphne, who’d done it once before to speak with Beatriz alone. The magic had cut out then, too, but it was different the second time, like she could still feel Daphne’s presence a few seconds longer, her stunned silence echoing in Beatriz’s mind before she too cut out.

But Sophronia can’t be dead. The thought is unfathomable. They came into the world together: Beatriz, Daphne, then Sophronia. Surely none of them could leave it alone.

No matter how many times Beatriz tells herself that, though, she never fully believes it. She felt it, after all, like a heart clawed out of her chest. Like something vital lost.

The sound of the lock scraping open echoes in Beatriz’s cell and she turns toward the door, expecting one of the Sisters to bring her next meal, but the woman who enters is empty-handed.

“Mother Ellaria,” Beatriz says, her voice rough after so little use these past days.

Mother Ellaria is the Sister who greeted Beatriz upon her arrival, leading her to her cell and giving her a change of clothes that look identical to what the older woman wears herself. Of those clothes, Beatriz has only put on the gray wool dress. The headdress still sits at the foot of her bed.

In Bessemia, it was a great honor for Sisters to don their headdresses. There were ceremonies for them—Beatriz herself had attended several. It was a celebration to honor a woman’s choice to devote herself to the stars above all else.

But Beatriz has chosen nothing, so the headdress remains off.

Mother Ellaria notes this, her eyes moving from Beatriz’s messily braided red hair to the headdress sitting on the bed. She frowns before looking at Beatriz once more.

“You have a visitor,” she says, disapproval filling every syllable.

“Who?” Beatriz asks, but Mother Ellaria doesn’t answer, instead turning and walking out of the room, leaving Beatriz no choice but to follow her down the dark hallway, her imagination running wild.

For an instant, Beatriz imagines it is Sophronia—that her sister has traveled from Temarin to assure her that she’s alive and well. But it’s far more likely to be her onetime friend Gisella, come to gloat again, or Gisella’s twin brother, Nico, here to see if a few days in the Sororia have changed her mind about his proposal.

If that’s the case, he’ll leave disappointed. Much as she hates it here, she prefers it to returning to the Cellarian palace while Pasquale lives out the rest of his life in the Fraternia on the other side of the Azina River.

Her chest tightens at the thought of Pasquale—disinherited and imprisoned because she convinced him to trust the wrong people.

They haven’t seen the last of us, Pasquale said after their sentence for treason had been handed down. And soon enough, they’ll wish they’d killed us when they had a chance.

She lets the words echo in her mind as she follows Mother Ellaria down the dimly lit hallway, running through a mental list of all the ways she could overtake the frail older woman and escape . . . but escape where? The Alder Mountains are treacherous terrain even for those who are prepared to scale them. If Beatriz were to escape, alone, with nothing more than a dress and cotton slippers, she wouldn’t stand a chance of living through the night.

Her mother always cautioned patience, and while it has never been Beatriz’s strength, she knows it’s necessary now. So she keeps her hands at her sides and trails after Mother Ellaria as she rounds a corner, then another before stopping at a tall wooden door and fixing Beatriz with a withering look, like she’s caught the scent of something rotten. Though Beatriz knows the woman dislikes her, she doesn’t think she’s responsible for that particular look.

“Due to the . . . status of your guest, I’ve allowed the use of my own office for your meeting, but I will return in ten minutes, not a second more.”

Beatriz nods, even more certain that it will be Gisella or Nicolo awaiting her—Nicolo, after all, is King of Cellaria now, and as his sister, Gisella’s status has been elevated as well, though Mother Ellaria might disapprove of them every bit as much as she disapproves of Beatriz.

Ignoring those thoughts, Beatriz steels herself and pushes the door open, stepping inside. She immediately stops short, blinking as if the figure before her might disappear.

But no matter how many times she blinks, Nigellus remains. Her mother’s empyrea has made himself at home in Mother Ellaria’s chair and watches her over steepled fingers as she enters. Her cell has no windows, and Beatriz lost track of the time of day soon after she arrived, but now she can see that it’s nighttime, the full moon shining through the window behind Nigellus, the stars brighter and bolder than usual.

It is the first time she has seen them in five days, the first time she has felt their light dance upon her skin. She feels dizzy with it, gripping her hands into fists at her sides. Magic, she thinks, though she still can’t quite believe it, even though she’s used her power twice now, accidentally, to call on the stars.

Nigellus notices the white-knuckled flex of her hands, but he doesn’t say anything. The door closes behind Beatriz, leaving them alone, but for a moment they only look at each other, silence stretching between them.

“Sophronia’s dead, isn’t she?” Beatriz asks, breaking the silence first.

Nigellus doesn’t answer right away, but after what feels like an eternity, he nods.

“Queen Sophronia was executed five days ago,” he says, his voice level and without any kind of inflection. “Along with most of the Temarinian nobility. Your mother had armies waiting at the border and amid the chaos, they seized the capital. With no ruler to surrender, she’s simply claimed it as her own.”

Beatriz sinks into the chair opposite the desk, all of the life leaving her in that moment. Sophronia is dead. She should have been prepared, should have expected that. Didn’t their mother always tell them never to ask a question they didn’t know the answer to? But hearing her biggest fear confirmed saps everything from her. Beatriz feels like a husk of a person.

“Sophie’s dead,” she says again, not caring about the rest of it. Not caring about her mother or her armies or the new crown she’s added to her collection.

“It is by pure luck that you and Daphne are not,” Nigellus says, drawing her out of her thoughts.

She looks up at him, wondering what he would do if she were to launch herself across the desk and pummel him. Before she can, though, he continues.

“It isn’t a coincidence, Beatriz,” he says. “The rebellions, the plots, the dead kings. The chaos.”

“Of course not,” Beatriz says, lifting her chin. “Mother raised us to create chaos, to plot, to stoke fires of rebellion.”

“She raised you to die,” Nigellus corrects.

The breath leaves Beatriz’s lungs, but after a moment, she nods. “Yes, I suppose she did,” she says, because it makes sense. “She must be terribly disappointed to have only gotten one out of three.”

“Your mother is playing a long game,” Nigellus says, shaking his head. “She’s waited seventeen years. She can wait a little longer.”

Beatriz swallows. “Why are you telling me this? To taunt me? I’m locked away in this miserable place. Isn’t that enough?”

Nigellus considers his next words carefully. “Do you know how I’ve lived this long, Beatriz?” he asks. He doesn’t give her a chance to answer. “By not underestimating anyone. I’m not about to start with you.”

Beatriz laughs. “I might not be dead, but I can assure you, my mother’s beaten me quite soundly.”

Even as she says the words, Beatriz doesn’t believe them. She promised Pasquale they would find a way out of this, and she knows that is the truth. But it is far better that Nigellus—and by extension the empress—believe her to be hopelessly broken.

Nigellus surprises her by shaking his head, a wry smile curling his lips. “You aren’t beaten, Beatriz. I think we both know that. You’re waiting to strike out, picking your moment.” Beatriz purses her lips but doesn’t deny it. He continues. “I’d like to help you.”

Beatriz considers him for a moment. She does not trust him, has never liked him, and there is a part of her that still feels like a child in his presence, small and afraid. But she is trapped in a deep hole and he is offering her a rope. There is nothing to lose by taking hold of it.

“Why?” she asks him.

Nigellus leans across the desk, resting on his elbows. “We have the same eyes, you know,” he says. “I’m sure you heard the rumors in Bessemia, that you and your sisters were fathered by me.”

If that was a rumor, it had never made it to Beatriz’s ears. But he’s right—his eyes are like hers, like Daphne’s are, like Sophronia’s were: a pure, distilled silver. Star-touched, the eyes of children whose parents wished for them using stardust or, in much rarer cases, when an empyrea wished on a star, causing it to fall from the sky. When Beatriz was sent to Cellaria, her mother gave her eye drops to hide the hue of her eyes, a hue that would mark her as a heretic in a country that viewed star magic as sacrilegious. When she was sent to the Sororia, she wasn’t allowed to bring any possessions with her, including the eye drops, so her eyes have returned to their natural silver, but she supposes that after using a wish to break a man out of prison, star-touched eyes are the least of her problems.

As if reading her mind, Nigellus nods. “We have been touched by stars, you and I. Made, in part, by the stars. Your mother wished for you and your sisters, and I pulled down stars to make her wish come true. I assume my own mother used stardust to wish for me, though she died before I could ask her.”

Your mother wished for you. It was a rumor Beatriz had heard, of course, but while wishing with stardust was relatively common, the wishes empyreas made on stars, bringing them down from the sky in the process, created strong enough magic to make miracles happen. Miracles like her mother becoming pregnant with triplets when her father had notoriously never before fathered a child, legitimate or not even with the assistance of copious amounts of stardust, in his eighty years. But even though an empyrea wishing on stars is rare, because stars themselves are a finite resource, Beatriz isn’t surprised her mother crossed that line. If anything, it is one of the smallest trespasses she’s made.

“And,” Nigellus continues, watching her closely, “being star-touched sometimes comes with its own gift from the stars.”

Beatriz forces her face to remain impassive, her thoughts sealed away. Twice now she has wished upon the stars and twice those wishes have come true, leaving stardust in their wake. One in ten thousand people can bring down the stars with magic—Beatriz never thought she’d be one of them, yet now she is sure of it. But they are in Cellaria, where sorcery is a crime punishable by execution, and Nigellus has already admitted that her mother wants her dead. She isn’t about to hand him a dagger to turn on her.

“If every silver-eyed child were an empyrea, the world would be a mad place,” she says after a moment.

“Not every silver-eyed child,” he says, shaking his head. “Not every star-touched child—in most the talent lies dormant, like in your sisters, never woken. But it isn’t dormant in you.”

When Beatriz’s expression doesn’t change, his eyebrows lift. “You know,” he says, leaning back in his chair and looking at her with appraising eyes. “How many times have you done it?”

“Twice,” she admits. “Both times accidentally.”

“That’s how it is at first,” he says. “The magic comes in fits, often brought on by extreme bouts of emotion.”

Beatriz thinks of the first time she called on the stars, when she was so overcome with homesickness she thought it might break her. And the second time, when she wanted nothing more in the world than for Nicolo to kiss her. Painful as it is to admit now, in light of his betrayal, she knows she was quite overcome with emotion then, too. She was such a fool.

“It doesn’t matter what talents I may or may not have,” she says, pushing to her feet. “They suspect what I can do and so I’m kept in a windowless room all night. Unless you have a way of getting me out of this place—”

“I do,” he interrupts, inclining his head toward her. “If you agree to my offer, you and I will walk out of here tomorrow night. You could be back in Bessemia in just a few days.”

Beatriz tilts her head, eyeing him thoughtfully for a moment as she weighs his offer. It isn’t that it is a bad one, but she suspects she can push him further. “No.”

Nigellus snorts. “You don’t even know what I want,” he says.

“It doesn’t matter. I don’t want you and me to walk out of here. If you’re getting me out, you need to get Pasquale out as well.”

Beatriz doesn’t know if she’s ever seen Nigellus surprised, but he’s surprised now. “The Cellarian prince?” he asks, frowning.

“My husband,” she says, because while the marriage has never been consummated—never will be consummated—they made vows to each other, both during and after their wedding. And they are vows Beatriz intends to keep. “He’s being held by the Fraternia on the other side of the Azina River, just as I am here, on trumped-up charges of treason.”

Nigellus gives her a knowing look. “From what I’ve heard, the charges had merit.”

Beatriz clenches her jaw but doesn’t deny it. They had plotted to overthrow Pasquale’s mad father, that was true. Treason might even be considered a modest description—they’d also taken part in a jailbreak of another traitor, and Beatriz was guilty of violating Cellaria’s religious laws by using magic. “All the same. If you can get both of us out, then maybe we can talk about your terms.”

Nigellus pauses for a moment before nodding. “Very well. I will get you and your prince to safety, out of Cellaria.”

She looks at Nigellus, trying to size him up, but it is impossible. There is no understanding Nigellus, and she would be a fool if she didn’t expect that he is two steps ahead of her, playing a game she doesn’t know the rules of. They are not on the same side in this, they do not have the same goals.

She should not trust him. But she doesn’t have a choice.

“We have a deal.”