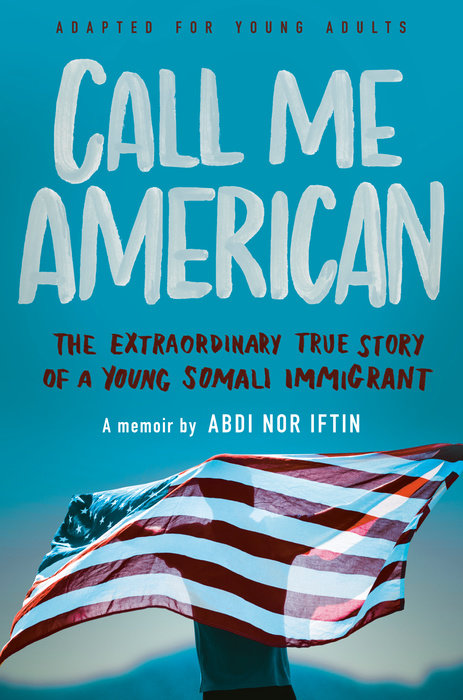

Call Me American (Adapted for Young Adults)

Author Abdi Nor Iftin

Call Me American (Adapted for Young Adults)

Adapted from the adult memoir, this gripping and acclaimed story follows one boy's journey into young adulthood, against the backdrop of civil war and his ultimate immigration to America in search of a better life.

Abdi Nor Iftin grew up amidst a blend of cultures, far from the United States. At home in Somalia, his mother entertained him with vivid folktales and bold stories detailing her rural, nomadic upbrinding. As he grew older, he spent his…

Adapted from the adult memoir, this gripping and acclaimed story follows one boy's journey into young adulthood, against the backdrop of civil war and his ultimate immigration to America in search of a better life.

Abdi Nor Iftin grew up amidst a blend of cultures, far from the United States. At home in Somalia, his mother entertained him with vivid folktales and bold stories detailing her rural, nomadic upbrinding. As he grew older, he spent his days following his father, a basketball player, through the bustling streets of the capital city of Mogadishu.

But when the threat of civil war reached Abdi's doorstep, his family was forced to flee to safety. Through the turbulent years of war, young Abdi found solace in popular American music and films. Nicknamed Abdi the American, he developed a proficiency for English that connected him--and his story--with news outlets and radio shows, and eventually gave him a shot at winning the annual U.S. visa lottery.

Abdi shares every part of his journey, and his courageous account reminds readers that everyone deserves the chance to build a brighter future for themselves.

FOUR STARRED REVIEWS!

An Excerpt fromCall Me American (Adapted for Young Adults)

1

Under the Neem Tree

I was born under a neem tree, probably in 1985. Neem trees grow everywhere in Somalia, with fragrant blossoms like lilacs and medicinal bitter sap that heals sores. People everywhere in Somalia brush their teeth with those twigs. Their green fruit turns yellow and juicy, a tasty treat for the birds. The trees’ limbs spread wide and give shelter from the sun--a good place to have a baby. A good place to be born.

I was born into a culture where birthdays are not celebrated, or even recorded. This became a problem for me when I left Somalia and entered the world of documents and paperwork. My first birthday record was in Kenya at a refugee registration center. The officers there did not bother to ask me when I was born, because they know Somalis have no idea. They simply wrote down my birthday as January 1, 1985. To them, every Somali is born on New Year’s Day. Arriving in America was different. Here the officials said I had to come up with…

1

Under the Neem Tree

I was born under a neem tree, probably in 1985. Neem trees grow everywhere in Somalia, with fragrant blossoms like lilacs and medicinal bitter sap that heals sores. People everywhere in Somalia brush their teeth with those twigs. Their green fruit turns yellow and juicy, a tasty treat for the birds. The trees’ limbs spread wide and give shelter from the sun--a good place to have a baby. A good place to be born.

I was born into a culture where birthdays are not celebrated, or even recorded. This became a problem for me when I left Somalia and entered the world of documents and paperwork. My first birthday record was in Kenya at a refugee registration center. The officers there did not bother to ask me when I was born, because they know Somalis have no idea. They simply wrote down my birthday as January 1, 1985. To them, every Somali is born on New Year’s Day. Arriving in America was different. Here the officials said I had to come up with a birth date and stick with it for the rest of my life. It’s a strange thing to choose your own birthday. But there I was. I chose a date around the middle of the year, which would be equally close to whatever my real birthday was: June 20, 1985.

My parents don’t know the day of my birth, but my mom remembers it was very hot. The blazing sun had turned the streets of Mogadishu ash white and the rooms of our small block house into bread ovens. Mom was under the shade of the neem tree, resting on a jiimbaar, a bed made of cow leather stretched over sticks. Our neighbor Maryan cooled Mom’s head with a fan woven from straw, and cleaned the blood. The women of the neighborhood brought fragrant resins and incense like myrrh and uunsi. For me they brought xildiid, the root of a plant that is mixed with water to bathe and protect the baby.

Somalia was once called the Land of the Perfumes; before the wars began, my country exported fragrant and medicinal plants all over the world. My mom remembers somagale, a seasonal plant that sprouts from the ground in the rainy season. She would uproot the plants, crush them, and apply the paste to any wounds. Mom still believes in those traditional plants that cure everything. She believes knowledge of them has helped her survive anywhere. My mom worried I would not be as strong as her because people in the city don’t know how to survive off the land. I tell her I have learned other ways to survive.

The moment I appeared, Maryan ran down the street to break the good news to my dad that a boy was born (boys are much more appreciated than girls in Somalia). My dad took a day off from work and partied with his friends, buying them qat leaves, a stimulant like strong coffee chewed by men in Arabia and the Horn of Africa. Somali culture dictated that my dad had to stay away from the house while my mother was giving birth; he would stay at his friend Siciid’s place for forty days, the amount of time a woman is supposed to remain chaste after labor. He visited us, as a guest in his own house, during the day. Mom was still sleeping under the neem tree, near clay bowls and glass jars full of porridge and orange juice. Out of respect for my dad she covered her hair while he was there, looking down as she answered his questions. They would never kiss or hug in public. He stood tall and aloof from her bed, examining me, his second son, lying next to Mom.

The women perfumed the rooms of the house and swept the yard bent over, using a short broom. They came in and out. That same evening, Maryan walked in with ten men, all of them respected local religious leaders in the community, known as sheikhs. They wore beaded necklaces and beards. They circled the jiimbaar in the yard where I was lying next to Mom. Some women were cooking a big pot of camel meat; others were mixing a jar of camel milk with sugar and ice cubes from the store. Camel meat and sweet milk together are called duco, a blessing for the newborn. For an hour the sheikhs blessed me, verse after verse, very loud, which makes the blessing greater. Afterward, they all sat on a mat on the ground, washed their hands in a dish of water, and feasted on the camel meat and milk. This blessing and feast meant I would grow better, be healthy and obedient to my parents.

Soon after I was born, Mom went back to doing her housework, with me tied to her back so that she was there for me whenever I cried out for milk. She watched me crawl out of the shade of that same neem tree into the scorching heat of the sun, and she was there when I took my first steps on the hot dusty ground. At bedtime she told me Somali folktales and sang lullabies like “Huwaaya Huwaa.” Mom and her stories were my universe.

Mom likes to call herself the brave daughter of her brave parents. Her name is Madinah Ibrahim Moalim. She was named Madinah after the holy city in Saudi Arabia, where the Prophet Muhammad is buried. It was her parents’ biggest dream to visit Mecca and Madinah, to make the pilgrimage known as the hajj, but unfortunately, they never got to. Mom too wants to visit before she dies. Growing up with a huge number of Somali exiles returning from Saudi Arabia, I never understood why my family wished to see a place where Somalis are unwelcome. It would be many years before I realized that Somalis are pretty much unwelcome everywhere, and dreams are all we have.

When Mom was growing up, her parents were always moving with the goats and camels. It must have been a little before Somalia got independence from the Italians in 1960. She never saw Italian or British colonialists--the Europeans who had taken over the land--but remembers her parents talking about people with no skin that they had seen driving back and forth. Mom says it does not matter how old she is, but she knows she is as old as her camel Daraanle, who was also born the day she was. Her family had almost five hundred camels, goats, and cows in total. They didn’t know how to count with numbers, but they named and marked every one and could keep track of them by their names. They provided the family with milk, meat, and transportation, but there were far more animals than they needed for food. Somali herdspeople have no permanent home, no belongings besides clothes, some jewelry, and cooking utensils. Their wealth is the size of their herd. They have no insurance payments, no loans, no future plans, nothing to worry about except lions and hyenas. To them, there are only two days: the day you are born, and the day you die. Everything in between is herding animals.

My grandparents on both sides were proud pastoralists, people of the land. They herded their animals across the Bay region in south central Somalia, always moving to find water. They had never heard of Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, or even Somalia itself, much less Nairobi or New York. The Bay region lies between the Jubba and the Shabelle Rivers, which nourish the soil. It has more livestock than anywhere else in Somalia and is famous for its gorgeous Isha Baidoa waterfall. The wide grazing land was all they knew.

Nomads of Bay region enjoy two rainy seasons over the year: Dayr, with light rains, begins in mid-October; gu brings heavy rains in mid-April. As the clouds build, the animals can smell the coming rain and they dance in anticipation. The people see the excitement of the animals, and they raise their hands to thank God: “Alhamdulilah!”

The rains mean plentiful water, so the nomads can finally settle down for a few months and build their makeshift huts from sticks carried on the backs of camels. At night the animals stay close to the hut in their corral, and the families sit around a fire near them. They dance with songs for the animals. There is laughter and fresh water and joy. A good time for stories, folktales, poems, and delicious meals of corn and meat. In his time, Iftin, my grandfather, would tell his own brave stories. He would talk about the day he met a pride of lions face to face near his house and chased them away for a mile. Eventually, the rains stop, the water dries up, and the nomads pack up and move on.

My parents as well as grandparents could name their own great-great-great-grandparents; they could spend a whole night telling the stories they have passed down. All these ancestral names carry pride; every single one of them was a brave man or woman, someone who owned many livestock and was well known in the area and probably killed a lion. My parents never talked about their lives without talking about the lives of their parents and ancestors because, to Somali nomads, there is no individual life, only the life of your family. And like their ancestors, my parents followed the Muslim rules. Women have to respect their husbands. Men have power over everything. My parents never questioned these rules or how they came about.

My mom, Madinah, was a very beautiful nomad girl, tall and slim, with dark hair, a long neck, and beautiful eyes. One summer day at a watering hole somewhere in Bay region, my dad, Nur Iftin, and his herd encountered my mom and hers.

My dad says he could not take his eyes off my mom. He had never seen such a beautiful woman. Mom was barefoot, wearing her long guntiino dress, which goes over only one shoulder, a necklace of black wooden beads, and metal bands around her upper arms. The scars on her neck and arms said without words how brave she was fighting wild animals.

They were both proud members of the Rahanweyn clan. So when they met, it was friendly. Dad was in his macawis, a knee-length cloth wrapped tightly around his waist. He wore his nomad sandals made of animal leather. His camels mixed with Mom’s goats around the watering hole. He approached her, and he bragged about his wealth, the animals, which is the only pickup line in the nomadic culture.

My mom liked him at first sight. Not many men were even taller than my tall mom, but he towered over her. He had a scar on his forehead that showed he had also wrestled wild animals. His high Afro hairstyle crowned his head and wide shoulders. His dusty feet showed that he had walked miles and was still not tired. As he stood there, he introduced Mom to his favorite camels, naming them as they grazed. They also had names for the wild animals that threatened their herds. They talked about Fareey, a local lion who had been terrorizing the herds. Fareey was named for his missing toe, which made his footprints in the clay distinct. Fareey and his pride killed many animals, including some belonging to my parents’ families, after dark. My dad swore that he would find Fareey and his pride and kill them all to protect my mom’s goats. He never did find that lion, but it was a way to show my mom that he could care for her.

After their first brief meeting, my parents searched for each other for a couple of months. When they finally met at another watering hole, my dad believed his prayers had been answered. Now Nur Iftin could not hide his love for Madinah and said he wanted to marry her. She did not say yes or no, but grinned and looked down coyly. It was a yes.

Dad arranged a meeting with her parents, and one day both families met in a place near Baidoa, the biggest city in the region, where the agreement was negotiated: fifty camels as a dowry, the price my dad’s parents paid to my mom’s parents.

The wedding happened in a town called Hudur, about sixty miles from Baidoa. This was the rainy season, so the animals were fat, and there was so much meat and milk at the wedding. Mom was in a mud hut all day with what they called the expert women, who told her stories about what would happen on the wedding night. It was a rented hut; they had to deposit goats to stay there. Neither of them had ever seen a banknote or a coin. At the same time, my dad was in a neighbor’s hut with the men teaching him about the first days of marriage.

My parents spent most of their early marriage walking miles every day into no-man’s territory with their herds. No one stopped them or asked who they were. It was a peaceful time. The land beneath their feet was scorching hot. They believed Earth was flat and that it was Allah’s land; they were only guests. It rains when Allah wills, it turns dry when Allah wills. Animals and humans die when Allah wills.

In the bush, nomadic Somali men and women work together, talk freely with each other, and even play games together. To survive on the land, a husband and wife must work as a team to make sure their animals are grazed well and that they all get back home by dusk. My dad had introduced my mom to several games, like high jump, sprint running, and chasing dik-diks, the little antelopes not much bigger than a cat. They would hold sticks five feet high, then take turns jumping over them. Mom learned to jump and land without stumbling. Mom was shy and respectful to her husband, but when it came to games and fun, she was a fierce competitor. They sprinted together across the bush, leaping over thornbushes while chasing the fast dik-diks.

Bay region is famous in Somalia for growing corn, beans, rice, sesame, papayas, mangoes, and the tree that produces frankincense resin. Most of that resin is bought by the Catholic church in Rome, but my parents knew nothing of Rome or Christianity. To them the most amazing place in the world was the Isha Baidoa waterfall. It was like their vacationland. During their nomadic travels they stopped twice a year to shower under the gushing water.

The city of Baidoa is called Baidoa the Paradise for both the nearby waterfall and the fertile red soil. Corn and masago, a type of grain, grow among the mango and banana trees. In the center of town is the huge Afar Irdoodka market, where people come from all across the country to buy and sell food, medicinal herbs, and supplies. Everywhere in that city, donkeys loaded with supplies are moving toward the market.