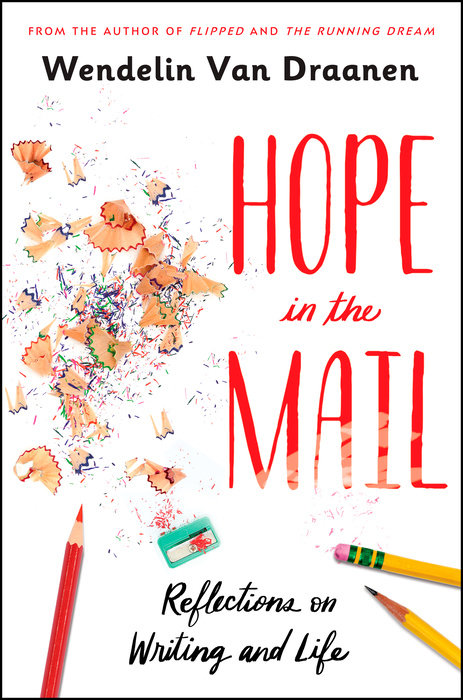

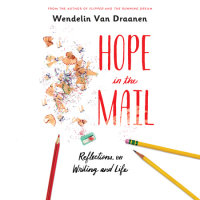

Hope in the Mail

Author Wendelin Van Draanen

Hope in the Mail

Want to write a novel? This book is the motivation you need! Part writing guide and part memoir, this inspiring book from the author of Flipped and The Running Dream is like Bird by Bird for YA readers and writers.

Wendelin Van Draanen didn't grow up wanting to be a writer, but thirty books later, she's convinced that writing saved her life. Or, at least, saved her from a life of bitterness and despair. Writing helped…

Want to write a novel? This book is the motivation you need! Part writing guide and part memoir, this inspiring book from the author of Flipped and The Running Dream is like Bird by Bird for YA readers and writers.

Wendelin Van Draanen didn't grow up wanting to be a writer, but thirty books later, she's convinced that writing saved her life. Or, at least, saved her from a life of bitterness and despair. Writing helped her sort out what she thought and felt and wanted. And digging deep into fictional characters helped her understand the real people in her life better as well.

Wendelin shares what she's learned--about writing, life, and what it takes to live the writing life. This book is packed with practical advice on the craft: about how to create characters and plot a story that's exciting to read. But maybe even more helpful is the insight she provides into the persistence, and perseverance, it takes to live a productive, creative life. And she answers the age-old question Where do you get your ideas? by revealing how events in her own life became the seeds of her best-loved novels.

Hope in the Mail is a wildly inspirational read for anyone with a story to share.

An Excerpt fromHope in the Mail

1

Writers’ Gold

Write what you know. It’s a good adage, and a manageable place to start. Many first novels are based on the author’s experiences, so take a look at what treasures are already stored in your vault.

Before I was published (but after I had finally begun letting on to family that I was trying to be), an uncle of mine asked me how I thought I could possibly be a writer. “You’re too young to be a writer. You need more experiences.”

Gee, thanks. And yes, seeds of doubt can quickly grow into weeds in your garden of worthiness.

But here’s the reality: No matter how young you are, you have experiences. You have knowledge. You have feelings and observations and thoughts that are worthy of exploration. You can arrive at conclusions that will broaden the thinking of others, or just paint a picture of life from your perspective. It’s often the small stories with universal messages that touch us most deeply. We’re all humans, trying to find a way forward, longing for the place where we…

1

Writers’ Gold

Write what you know. It’s a good adage, and a manageable place to start. Many first novels are based on the author’s experiences, so take a look at what treasures are already stored in your vault.

Before I was published (but after I had finally begun letting on to family that I was trying to be), an uncle of mine asked me how I thought I could possibly be a writer. “You’re too young to be a writer. You need more experiences.”

Gee, thanks. And yes, seeds of doubt can quickly grow into weeds in your garden of worthiness.

But here’s the reality: No matter how young you are, you have experiences. You have knowledge. You have feelings and observations and thoughts that are worthy of exploration. You can arrive at conclusions that will broaden the thinking of others, or just paint a picture of life from your perspective. It’s often the small stories with universal messages that touch us most deeply. We’re all humans, trying to find a way forward, longing for the place where we feel at home.

My first published novel, How I Survived Being a Girl, was described as “Seinfeld for kids.” What the reviewer meant was that it was a story about nothing, as the sitcom was famously called “a show about nothing.”

Having your book be considered to be about nothing could be deflating, but I took it as a huge compliment. I loved Seinfeld. And saying that it was a show about nothing was as true as saying that it was a show about everything. Seinfeld was about both. It captured the human experience with humor and heart-zinging authenticity. It was a show about people living small lives in small apartments in a big city. No special effects, no outrageous sets. Just little glimpses into the lives of people muddling along.

All of us have that--a story about nothing that’s actually about everything. No matter how ordinary your environment may seem to you, if your story can capture the human experience within it, others will relate.

Don’t discount how extraordinary capturing the ordinary can be. And how difficult. You probably haven’t viewed it this way, but if you’re in school--as a student or as an educator--you are surrounded by writers’ gold. How a school works, the voices of the kids and the administrators, the rules and limitations, the curriculum and expectations . . . it’s all second nature to you. It’s workaday stuff, part of the grind.

But let’s turn that around. You have the background and details to write about a school environment naturally. The sights, the sounds, the smells, the mechanics of school life will flow from your fingertips. It’s easy for you! Do you know how many authors--especially kid-lit authors--would love to know what you know? Maybe they were in school once, but that was probably a long time ago. Things in education have changed. To get it right, they have to work at it, and work hard.

Likewise, if you have a job--no matter how boring or ordinary you think it is--the way it works, the conversations in the employees’ lunchroom, how your associates relate to each other and the boss . . . it’s all gold.

If you’re a dog walker, a babysitter, a dishwasher, a law clerk, a trash collector . . . it’s all gold.

And if you’re in a rough situation right now--turbulent home life, a bad neighborhood, even unemployed--turn it around. What you’re going through is hard and dark and frightening, but it’s also writers’ gold. Take notes. Document your experience any way you can. There are seemingly mundane details about your everyday life that will give a natural authenticity to your writing.

It’s all gold.

So pay new attention to the ordinary around you. Find the story inside it. And find the human connection, because the best stories are the ones that touch our hearts. Love, longing, triumph . . . these can be small and personal, yet they’re universal desires. You don’t have to save the world. Just save your character. And at the heart of that character is you.

So no matter what your situation is or how young you are, you have enough to paint a story with words, to make others hear you, see you, feel you.

Take a closer look at what you already know.

What’s inside your heart?

What’s inside your vault?

It’s a really good place to start.

2

Out of the Ashes

What turns a person into a writer?

Sometimes the unexpected. I came to it from a place of anger and pain. Horrible stuff happened to my family when I was in college. An arsonist burned down our business--an industrial facility my immigrant parents had spent twenty years building--and then my father passed away unexpectedly six months later. We were devastated emotionally and financially, and our faith in justice was shaken to the core. I’d jolt awake in the middle of the night relieved to have escaped a nightmare, only to realize, Oh, wait, no. That’s my life.

Unable to go back to sleep, I started writing. Scrawling, really, about how unfair the world was, how it was so wrong that such bad things could happen to good people, how small and helpless and lost I felt to be in the middle of this disaster, how the Big Bads--the people who had destroyed the business--were out there, free from any consequence of their actions.

I wouldn’t classify what I did as journaling. It was more slashing at the paper. I was alternately furious and heartbroken, or maybe both at once. I felt raw and deeply wounded, and the facts, my thoughts, my emotions poured out, oozed out, bled out. I wrote and I wrote and I wrote.

And it didn’t change a thing.

The Big Bads were still at large, no one came back to life, and there was still ash where dreams had once stood.

I started fantasizing about payback. Payback may be a bad idea, but the cornered, wounded animal doesn’t care. The cornered animal is desperate and primed to strike back.

Fortunately, the weapon handy during my middle-of-the-night jolts into reality was a pen.

Fortunately, I discovered that I could kill off my bad guys on paper.

And unexpectedly, this led me to the world of fiction, where you don’t have to stick to what really happened, where you can change the names of your bad guys a little, change the way things turn out a lot, and dole out payback that would land you behind bars if you tried it in real life. Torture, justice, murder . . . it was all available from the tip of a pen, no jail time required.

So, no. I didn’t start writing with literary aspirations.

I started writing because I needed to kill off some bad guys.

Clearly, what I really needed was therapy.

Turns out, writing is great therapy.

3

Putting Hope in the Mail

The first novel I wrote was an epic clash of good and evil. Weighing in at 627 pages, it had thinly concealed names, caricatured players, and a very visible ax to grind.

Yes, it was terrible.

But I didn’t know that!

I also didn’t know anything about publishing.

Well, other than that most publishing houses were located in New York City.

But now I needed to know! I had a masterpiece to place!

This was before you could query editors or agents or submit samples online. I got some preliminary information about the submission process by reading back issues of Writer’s Digest magazine, then went to the library, checked out a book called Literary Market Place, perused it for friendly-sounding names, and started shopping my manuscript.

Compelling query letter--check!

Self-addressed stamped envelope--check!

Ignore the no-multiple-submissions rule because who has time for that?--check!

Not a great (or even good) strategy. And (displaying compounded ignorance here) I was also under the common misconception that getting a book published meant becoming an instant millionaire. Consequently, I thought that placing my manuscript would bring an end to my family’s financial troubles. Or, at least, help out considerably.

So, yeah. Therapy and financial need. These were the forces fueling me. But then a strange thing happened. Each time someone in New York would agree to take a look at my full manuscript, I’d make a copy of it, box (yes, box) it up, and stand in line at the post office. And as I moved forward in the line, my heart would beat a little faster and I would tell myself that this was it. This editor was going to read and love my story. This editor was going to send me a million bucks and my family’s financial troubles would be solved.

And when it was my turn at the counter, I’d give the box a quick kiss for luck, pay the postage, and walk away with a little spring in my step.

Outside, the world felt renewed with possibility.

Things were going to change!

We were not defeated.

Hope was in the mail.

4

Today Could Be the Day

I put hope in the mail for ten years.

Actively and persistently, I sent out manuscripts and queries, and for ten years I was actively and persistently rejected by editors and agents in New York.

The rejection slips were usually generic--some version of We’re sorry. This is not right for us at this time. But please think of us again with your next project.

I shoved the slips inside a drawer.

Over time, they filled the drawer.

I moved them into a box.

Over time, they filled the box.

You’d think I’d have taken the hint: I didn’t have what it took to be published. So why did I keep trying?

Looking back, I think it had a lot to do with keeping hope in the mail. As my first manuscript was making the rounds in New York, I began working on a second story. Another epic clash of good and evil! This time, though, it was more removed from my own story. Characters were becoming . . . their own entities. Plot was more . . . flexible. There was real freedom in that, and I enjoyed it.

I also began reading about the craft of writing. I read everything I could get my hands on because I wanted to finally crack the code. I wanted to get inside structure and dialogue, pacing and theme.

So when my self-addressed stamped envelopes started coming back to me with rejections for my first novel, I was disappointed, but not crushed. I’d learned more about craft and could see now that, yeah, the first book was more therapy than literature. I got back to work, thinking, You didn’t like that story? Okay, well, wait ’til you read this one!

Having overlapping hope in the mail equipped me with the mantra Today could be the day. If I didn’t give up, if I kept submitting, kept learning, kept writing, kept trying, someday someone somewhere would read one of my manuscripts and want to buy it.

Today could be the day.

It’s a nice way to live your life, but it only works if you keep hope in the mail. This phrase doesn’t refer to just physical mail or email. Putting hope in the mail means putting yourself--your work, your wishes--out there however you can. It means actively creating the possibility for good things to happen.

Now, prepare for your hopes to be dashed--because undoubtedly they will be. But when that happens, the only course of action is to pick yourself up, redouble your efforts, and put hope back in the mail. Don’t let rejection or brusque (and occasionally cruel) critiques cause you to close in, close down, or give up. Don’t sit in a dark corner licking your wounds. If you disagree with the opinions of the rejecting party, send your work to someone else. I promise you that over time rejection gets less painful and becomes just part of the process.

In the case of literature, it’s not science, and I see now that that’s a good thing. There is nothing more ho-hum than a formulaic book. And what one editor may dismiss, another editor right next door may love. So get back in the ring! And while you’re waiting for a reply, shift your focus to a new project.

Do not wait around.

Nothing will reinvigorate you more than pouring your energies into something new.

Another thing that helped me endure ten years of rejection was not knowing it was going to be ten years. For all those years, I had a full-time job, and for many of them I also had two little kids. I got up each morning at five o’clock when my husband left for work, spent the next hour or so writing, then began my real day. I was constantly sleep-deprived. If I had known it would take ten years to get published, I almost certainly wouldn’t have made it.

But I didn’t know.

And every day I told myself, Today could be the day.

And then one day it was.

5

Defining Moments

Ten years is a lot of rejection for someone to take. And on the long and winding road to the day I finally got a “Yes,” I heard things like “It’s just too hard to get published” and “You have to know somebody in publishing” and “Maybe if you had an MFA, people would pay attention.”

These, uh, consoling and, uh, helpful statements were tempting to buy into during the many phases of feeling discouraged. Maybe there were just too many obstacles, too many reasons I wouldn’t succeed.

Any one of them would justify quitting.

So . . . what, then, made me keep going? Why did I think that, despite the odds, I could do this?

I trace the defining moment back to my first car.

A lot of kids I went to high school with got cars when they turned sixteen. Some got hand-me-downs, some got brand-new, off-the-car-lot, big-bowed beauties.

If I had asked my parents for a car of any kind, they would have laughed me out of the room. That’s just not the way things worked in our family. If I wanted my own car, I was going to have to buy it with my own money.

Desperate for a vehicle, I scoured our small town for one I could afford. Taking out a loan or buying something on credit never even crossed my mind. We didn’t do credit. We were taught to only buy what we could afford, and as a student without steady income, what I could afford would be paid for with money from babysitting, yard work, and summer jobs. This meant that what I could afford wasn’t much, but there were three for-sale-by-owner prospects in town at my price point, and a friend offered to drive me around to check them out.