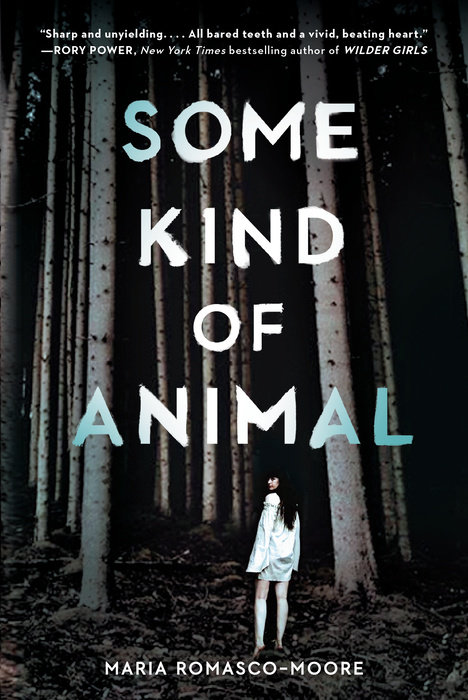

Some Kind of Animal

"Sharp and unyielding. I loved every page." --Rory Power, New York Times bestselling author of Wilder Girls

For fans of Sadie comes a heart-pounding thriller about two girls with a secret no one would ever believe, and the wild, desperate lengths they will go to protect each other from the outside world.

Jo's mother disappeared fifteen years ago. Everyone knows what happened to her. She was wild, and bad things happen to girls like that.

Now people are starting to talk about Jo. She's turning out just like her mom--and, like her, Jo does have a secret. It's not what people think, though. Not a boy or a drug habit. Jo has a twin sister.

The thing is, no one's ever seen Jo's sister. So when she attacks a boy from town, everyone assumes that it was Jo.

Now everyone thinks Jo is a liar, that she's crazy, that she's dangerous. But Jo is telling the truth. And that's the last thing her sister wants.

"A compelling, unpredictable, and uncompromisingly dark debut."--Kirkus

An Excerpt fromSome Kind of Animal

Chapter One

My sister and I sit side by side in the dark. She is pulling little bones out of her heart-shaped plastic purse and tossing them down the hillside onto the empty road below.

The bones are from a rabbit she caught earlier in the night. She ran out ahead of me, and by the time I reached her, she’d already stripped away most of the skin with her knife. Was gnawing on the raw flesh.

“You need a new dress,” I tell her.

“No,” she says, wriggling her bare feet in the dirt.

The truth is I’ve given her many new dresses, but she never wears them. She prefers to wear the lace-trimmed blue party dress I gave her when we were ten. It’s five years old now, full of rips and much too short. It only barely reaches her thighs.

“You look like a slut,” I tell her.

“No,” she says. She sticks her tongue out at me, throws another bone down the hill.

I shouldn’t have said that, but she probably doesn’t even know what the word means. I really should be home by now. The sun will be up soon.

Normally, I would be home by now, but tonight I am stalling, avoiding what I have to say.

My sister, Lee, and I don’t live in the same house. My sister doesn’t live in a house at all. She lives in the forest. She sleeps during the day and runs at night.

I snuck out this morning around three, an hour after the bar downstairs closed, half an hour after Aunt Aggie went to sleep. Aggie has raised me since I was a baby, since Mama went missing, but she doesn’t know about my sister. No one does.

No one but me.

Even I didn’t know I had a sister, until I was five. Until she appeared one night, coming out of the woods like a dream. I see her only in the small dark hours, when I can slip out my window, run with her through the trees, and slip back before anyone knows I’ve been gone.

I used to only manage it once or twice a week. This past summer, though, Aunt Aggie was busy with her new boyfriend, and my best friend, Savannah, was busy with an endless string of them and so I went to see my sister every night. No one was paying attention to me. No one cared. I could sleep all day.

But it’s October now.

My sister has run out of rabbit bones, so she picks up a big rock and throws that at the road instead. It bounces down the hill, hits the asphalt, and cracks in two.

“I can’t run with you tomorrow night, Lee,” I say.

“No,” she says.

“Yes,” I say. I’m not thrilled about it either--I love running at night--but I’ve got no choice. “I can’t run tomorrow night, or the night after that, or the night after that. I need more sleep. They sent a letter home from school.”

It’s true. I’m failing everything but chorus. If I don’t get my shit together I might have to repeat the whole ninth grade. Aunt Aggie was livid when she found out. She wanted to know what the hell was wrong with me, whether it was drugs or boys or just a relentless desire to piss her off at every opportunity. But I couldn’t tell her the real reason I’ve been sleeping through all the classes I don’t cut. The real reason I’m bone-tired constantly these days.

“You can run away,” my sister says.

Lee and I are twins. We’ve got the same build, straight up and down, though she’s far skinnier than me, skinny enough that people would probably whisper behind her back if they ever saw her, say she was anorexic or something. We’ve got the same plain face, though hers is smeared with dirt. Same mud-colored hair, except mine is chin length and hers hangs most of the way down her back in a snarled mat.

“I’ll come run with you once a week,” I say. “Okay? Saturday nights. Like I used to.”

“Run away,” she says again, insistent.

And sure, it would be nice if it were that easy. If I could just let everything go, stop trying to be everything everyone says I’m supposed to be--a good girl, a normal girl, a pretty girl, a cool girl, a smart girl, a girl who gives even half a shit about school.

My sister’s never gone to school and so to be perfectly honest she’s kind of dumb. I mean, she’s smart in some ways, knows more about the woods than anybody, but she can only read books that don’t have too many words. I used to bring her stuff from the library, comic books and picture books, but I’m banned now, after returning too many books with leaves pressed between the pages, dirt caked into the spines, spots of blood on the covers.

“You know I can’t run away,” I tell her, as I’ve told her a thousand times. “I have a life.”

Lee bares her teeth as she scowls, then reaches out to grab my arm, but I twist away and jump to my feet. I’m cutting it way too close.

“I’ll see you Saturday night,” I say. “I’ll bring you some chocolate or something.”

I try to run down the hill but end up mostly sliding. When I reach the bottom, my jeans are streaked with dirt. I turn and wave at my sister. She throws a pebble that hits me right in the shoulder and then she darts back into the trees.

I usually go the long way home, circling through the national forest, which surrounds my hometown of Lester, Ohio, on three sides. But the sky is growing more gray by the second, the morning light erasing the stars. So I head down the road, running on the shoulder, past the old abandoned high school with the blown-out windows and the outline of a girl spray-painted halfway up an inside wall. I wave at the painted girl. She just floats there, a ghostly silhouette, someone’s misplaced shadow half.

I cut through the No. 5 mine disaster Memorial Park and the empty Dollar General parking lot and then I run alongside the railroad tracks, that long string on which Lester is threaded like a small, dull bead.

In the old days, the hills around here were studded with mines, and freight trains carried away tons of coal every day. People called Lester “the magic city” because of how it sprang up almost overnight and grew like crazy. Half the people in Lester worked in the mines, but now, as Aunt Aggie likes to say, half the people in Lester work nowhere.

The sky is getting brighter. I push myself to run faster, heart racing. It must be nearly six. If Aggie catches me out she will lose her mind. It’s bad enough that she knows I’m failing. She isn’t strict, exactly, but she worries her head off if I give her half a reason. I am usually more careful than this.

When I finally reach Joe’s Bar and Grill, I sprint around the side and scramble up the crumbling wall. The bricks jut out unevenly here, and half the mortar has crumbled to dust. Little puffs of it fall away like cigarette ash as I climb.

I pull myself onto the rusty fire escape and force myself to go slow, easing my bedroom window open gently, wiggling it in its socket like a loose tooth.

When it’s open just far enough, I tumble inside, yank off my muddy clothes, shove them under the bed. I shut the window, jump into bed, pull the covers up to my chin. There’s no time for sleep and anyway I’m too keyed up from how close I cut things. Aunt Aggie will be knocking on my door any minute now, telling me to get up for school.

Sometimes I feel like two different people, loosely attached by the dawn. A girl with a secret shadow half.

When I’m with my sister I don’t have to think about school. I don’t have to think about anything. I can just exist. Breathe in and out. Move through the world. Run until all the stress and worry I’ve built up over the course of the day streams out of me. Sometimes I envy my sister, getting to live that freely all the time.

Usually I have more time to adjust, to move from one world to the other. From the person I am at night to the person I have to pretend to be in the day.

Now all I can do is stare up at the plastic stars on my ceiling, glowing their faint and sickly green, and wait.

Pastor Jones is sitting at the card table in the kitchen when I come out of my room. He’s wearing a faux silk bomber jacket with embroidered tigers and a black T-shirt with a white cross on it. He shoots me an idiotic grin.

“Will you get that toast for me, honey,” says Aunt Aggie, bustling around the tiny kitchen in her plaid robe. She’s making eggs. She only does that when the pastor is over. When it’s just us we have Cheerios.

“Good morning, Jolene,” says the pastor.

“Morning,” I say, which is my way of saying I hate you. I grab the toast right out of the toaster and it burns my fingers.

The pastor never used to stick around for breakfast. When he started staying nights, back at the beginning of summer, he would sneak out before the sun was up. I almost ran into him once in the alley behind the bar. He had that dumb jacket draped over one shoulder and his boots were untied. It was kind of funny: him sneaking out, me sneaking in. Toward the middle of summer, he’d creep down the stairs, wait a while, then make a big show of knocking on the front door. Aggie would greet him, pretend to be surprised, invite him in for eggs. I never commented on it and after a while they gave up pretending.

Aggie spoons a poached egg onto each of our plates. The pastor closes his eyes and holds his hands out over the table.

“Lord,” he says, “you are more precious than silver, more costly than gold, more beautiful than diamonds. Lord, you are darker than coal, you are slicker than oil, you are faster than a Ford Thunderbird. Nothing I desire compares with you. Amen.”

“Amen,” says Aggie.

My poached egg looks like a big lidless eye. I pretend it is the eye of God, watching over me. I poke it in the pupil with my fork and let the yolk ooze out.

The pastor thinks he’s so damn clever. When he first came to Lester two years ago, hardly anybody showed up to his church on Sundays, so he started coming around the bar and preaching to the drunks. Aunt Aggie used to laugh at him, call him a joke, but the drunks loved him, and after a while I guess she did too.

The pastor is shoveling sugar into his coffee. Aggie is lighting her cigarette on the stove burner. I want nothing more than to crawl back under the covers. I’ve started going to bed earlier on weeknights. I tuck myself in by ten some nights, but that’s still only five hours at best before I’m up again and running. Aggie can’t understand why I’m always so tired. She keeps threatening to take me to a sleep specialist, but I know she won’t. The nearest hospital is twenty miles away, in Delphi, and Aggie never goes more than ten minutes outside of Lester.

It’s a superstition she inherited from Grandpa Joe, who she loved more than anyone. He was the kind one, to hear her tell it, the one who protected Aggie and Mama, loved them, encouraged them. He was everything that Grandma Margaret wasn’t. But he drank too much and died of liver failure when Aggie was thirteen and Mama was ten. I don’t think Aggie ever really got over that. Maybe Mama didn’t either.

“I’ll be late for school if I don’t leave soon,” I say, which is a lie.

“Eat your breakfast, Jo,” says Aggie. “The pastor can ride you over.”

“Have you ever seen those pictures of Jesus where he’s carrying a lamb over his shoulders?” the pastor asks me in the car.

“No.” I lean my head against the car door, close my eyes, hope he takes the hint to shut the hell up. The pastor, unsurprisingly, loves to talk about Jesus. I’ve tried silence, sarcasm, eye rolling, but nothing can dissuade him.

“It’s a common picture,” the pastor goes on. “Do you know why Jesus is carrying the lamb?”

Because he’s really into CrossFit? No, the pastor would only take that as encouragement, an opportunity to make some awful joke of his own. I try silence.

“Back in Jesus’s day,” the pastor says, undeterred, “if a shepherd had a lamb that wouldn’t stop wandering off from the flock, what the shepherd would do is break the lamb’s legs.”

I make an involuntary sound of disgust and regret it immediately. It betrays that I was listening.

“The lamb would need to be carried until the legs healed, of course,” says the pastor, cheerily, “but afterward, you can be sure, that lamb would never wander again.”

“Whatever,” I say, to show the story had no effect on me, though the truth is I feel a bit ill. I’m doing my best to commit every word to memory so I can tell Savannah about it later. She already thinks the pastor is a creep, so she’ll eat this up.

We’re only about two blocks from school, but the light up ahead turns red. I silently curse it. The pastor’s shitty old car (vintage, he calls it) squeals to a stop.

“Look,” says the pastor. “I don’t know where it is you go when you sneak out at night. I don’t know what you do. I’m not sure I want to know.”

Well, shit. I stare out the window as hard as I can, but in my head I’m screaming. The goddamn pastor. Aggie’s such a heavy sleeper. Grandma Margaret was, too, when we lived with her. I thought I was being careful, thought I was getting away with it, but I should have realized not everyone sleeps as soundly as them.

“I know you went out last night,” the pastor says. “And twice last week.”

He’s wrong about that part, at least. I went out every night last week. And every night but one the week before. To see my sister, to run with her. I’ve been going out too often. I know that already.

“I can’t make you see things the way I do, Jolene,” says the pastor, “but whatever it is you’re doing, I want you to think real hard about whether it’s worth it.”