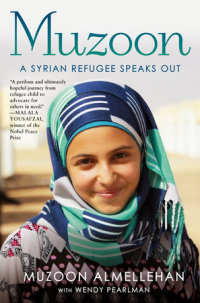

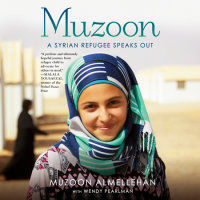

Muzoon

Author Muzoon Almellehan Wendy Pearlman

Muzoon

“Muzoon takes readers on her perilous and ultimately hopeful journey from refugee child to advocate for others in need.”

—Malala Yousafzai, bestselling author and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize

When her family had to flee Syria, 14-year-old Muzoon was told to pack only the most essential things—and so she packed her schoolbooks.

This is the inspiring true story of a Syrian refugee who fought hard for what she needed—and grew into one of the world's leading advocates…

“Muzoon takes readers on her perilous and ultimately hopeful journey from refugee child to advocate for others in need.”

—Malala Yousafzai, bestselling author and winner of the Nobel Peace Prize

When her family had to flee Syria, 14-year-old Muzoon was told to pack only the most essential things—and so she packed her schoolbooks.

This is the inspiring true story of a Syrian refugee who fought hard for what she needed—and grew into one of the world's leading advocates for education.

This eye-opening memoir tells the story of a young girl's life in Syria, her family's wrenching decision to leave their home, and the upheaval of life in a refugee camp. Though her life had utterly changed, one thing remained the same. She knew that education was the key to a better future—for herself, and so that she could help her country. She went from tent to tent in the camp, trying to convince other kids, especially girls, to come to school. And her passion and dedication soon had people calling her the "Malala of Syria."

Muzoon has grown into an internationally recognized advocate for refugees, for education, and for the rights of girls and women, and is now a UNICEF goodwill ambassador—the first refugee to play that role.

Muzoon's story is absolutely riveting and will inspire young readers to use their own voices and stand up for what they believe in.

An Excerpt fromMuzoon

Chapter 1

“Motorcycle!” my brother yelled.

I came to a full stop. I had brought the ball the distance of three houses. The rocks that we used as goal markers were nearly within reach. But when you played soccer in the street, you had to be ready to pause for traffic.

I placed my foot on the ball and looked right and left. No motorcycles.

“Tricked you!” Mohammed crowed, stealing the ball. He turned toward the rocks at the other end of the street.

I ran after him as fast as I could. My cousins Tayyim and Razi picked up speed behind me. Tayyim rushed to defend our goal. Razi positioned himself in case Mohammed decided to pass. I caught up within a breath of Mohammed, but he dodged my kick. I ran harder and reached my foot out long. This time, I heard the plastic of my flip-flop thump the ball. I pushed him out of the way.

The ball was now back under my control, and I wasn’t about to lose it again.

Chapter 1

“Motorcycle!” my brother yelled.

I came to a full stop. I had brought the ball the distance of three houses. The rocks that we used as goal markers were nearly within reach. But when you played soccer in the street, you had to be ready to pause for traffic.

I placed my foot on the ball and looked right and left. No motorcycles.

“Tricked you!” Mohammed crowed, stealing the ball. He turned toward the rocks at the other end of the street.

I ran after him as fast as I could. My cousins Tayyim and Razi picked up speed behind me. Tayyim rushed to defend our goal. Razi positioned himself in case Mohammed decided to pass. I caught up within a breath of Mohammed, but he dodged my kick. I ran harder and reached my foot out long. This time, I heard the plastic of my flip-flop thump the ball. I pushed him out of the way.

The ball was now back under my control, and I wasn’t about to lose it again. I went flying toward the rocks of our goal. Al-l-l-lmost there—kick! The ball sailed between the two rocks.

“Goal!” I shouted, pumping both fists overhead.

“Ughhhh,” Mohammed groaned, his head dropping into his hands.

I was twelve and my brother Mohammed exactly one year and eleven days younger than me. We were so close, you’d have thought we were twins. At the same time, we were always jealous of each other. If I got ketchup-flavored potato chips, he demanded ketchup-flavored potato chips. If he drank tea, I wanted to drink tea. And I don’t even like tea! My three cousins closest in age were also boys, which made me the only girl in our pack of five.

Soccer was our obsession. We didn’t really know the rules, so we made up our own. Still, we took the game very seriously. Whoever lost could expect to be taunted.

Mohammed was usually on a team with Razi, who was only a few months younger than me. I paired up with our other cousin Tayyim. Tayyim’s older brother Mansour sometimes joined us, too. Mansour was the largest and strongest among us. He kicked the ball so hard that it scared me—not that I would admit it. So it was fine with me if he was absent. That meant I was the oldest and the one in charge, which was how I liked it.

Mohammed and I got into plenty of arguments. But if either of us got into an argument with one of our cousins, we became a united front. We wouldn’t allow our cousins to come to our house. We’d declare our own fields and groves off limits. They would do the same to us. If one of them set foot on our property, we would demand an explanation. Or we would get back at them by entering their fields, even if we had to sneak there in the middle of the night.

One epic fight began after Mohammed and I planted a watermelon seed. Mohammed had a knack with plants, and he carefully tended this one until there was a big watermelon, almost ripe. Mansour talked about how tasty it would be, and how he couldn’t wait to get a slice. When we woke up one morning and found it missing, we immediately knew the thief. Mohammed and I marched across the field to his house, and I gave him our signal to show that we were refusing to speak to him: I put my index finger to my tongue and thrust it toward the ground. Usually our angry silences lasted only hours. But the War of the Watermelon lasted weeks.

Even our parents respected our feuds. If we were in a fight with Tayyim and Mansour, Uncle Adnan and Aunt Ayida wouldn’t bring them when they came to visit. Dad wouldn’t take us if he went to visit them.

Then we would reconcile, and there was nothing our parents could do to keep us apart.

I grabbed the ball, and the four of us sat on the side of the road.

“Fake motorcycle is a new one,” I said, kicking dirt in Mohammed’s direction. He was always inventing new ways to cheat.

He grinned and batted his eyelashes. In our baby portraits we all had long eyelashes. While everyone else’s eyes caught up with their lashes, Mohammed’s remained outsized.

“Yeah, you usually just claim a broken flip-flop,” Tayyim added.

Someone’s flip-flop fell apart at least once a week, so calling out a ripped shoe was a believable way to halt the game when you were about to lose.

I brushed the dirt off my T-shirt, which was bright green with a large number 10 on the back. “I don’t want to play with cheaters.” I stood up, taking the ball with me.

“Come on, Muzoon. Let’s keep going,” Razi begged.

“No, I’m going home.” I started walking away, ignoring the pleas behind me. When I got a foot from the stone markers, I put the ball down and shot it straight between them.

“Goal!” I shouted as I jumped up and down. One of my flip-flops slipped off and sailed through the air.

“That’s not fair!” Mohammed wailed.

Okay, yes. I cheated sometimes, too.

Chapter 2

It was around two p.m.—time for all of us to go to our respective houses for lunch. Razi lived a few minutes in one direction and Tayyim a few minutes in the other. My family lived in the middle, in a house that Dad built after we were born. When Mohammed and I got to our door, the aroma of mint, garlic, and cilantro greeted us. “Shish barak,” we said at the same time.

Our grandmother had prepared the traditional stew of meat dumplings boiled in yogurt. Jadati (my grandmother) and Jidi (my grandfather) had grown up as Bedouins, nomads, in the desert. They traveled with their flock, tending to their sheep and goats, and all their cooking used meat and dairy. Mostly I hated milk. I refused to drink it, to the point where it affected my teeth. But when Jadati cooked with milk, it somehow always tasted delicious.

When my father was born, my grandparents gave up the nomadic life and settled in Dara’a, a province in the southwest corner of Syria. They built a house in the small town of Izraa, where our family has lived since. After Jidi died, Jadati moved in with us, which was really helpful, especially after my mom moved out.

Mohammed and I washed our hands and joined the others in one of the sitting rooms. The thin mattresses placed directly on the floor were great for jumping, flipping, and wrestling. The big pillows were perfect for reclining. They were also good for throwing, as necessary. If we were at home, this is where you’d find us.

Dad sat cross-legged on the mat, where we ate our meals together. My four-year-old brother, Zain, leaned on him from one side, and my eight-year-old sister, Yousra, leaned on him from the other. Jadati placed the steaming bowl of stew in the center of the mat. We each took a spoon and dug in.

“How was school today?” Dad asked.

Mohammed shrugged. He wasn’t very interested in school.

“I have a story from English class,” I offered, tearing a piece off a round, flat bread and dipping it into the stew. “Miss Leila said everyone who didn’t do their homework must go out into the hallway and wait. So a few other students and I went into the hallway.”

Jadati and Dad looked at me in dismay.

“Then Miss Leila went from desk to desk, asking students to read some text. She wanted to make sure they understood the lesson. She kept asking them to translate the term al-bitriq tayir into English. But no one she asked could do it.”

I saw on Dad’s face that he guessed where the story was going.

“So from the hallway, I called out the answer: ‘Penguin!’ And Miss Leila said, ‘Muzoon, please go back to your seat.’ ”

Dad helped Zain spoon out a dumpling. “It’s fine to be smart and resourceful,” he began.

I blushed.

“But it’s better to do your homework,” he finished.

I thought he’d be pleased that I got the right answer. But Dad did not seem impressed.

“Remember when you were a preschooler?” Dad asked. I knew where he was going, because he told this story all the time. When I was just four years old, Aunt Zihriya, one of Dad’s sisters, was the principal of an elementary school and would sometimes take me to work with her. They let me sit in on the first-grade class. I was what they called a “listener student.” I didn’t go every day and didn’t do any assignments. But at the end of the year, the teacher gave me a diploma and a report card.

“Congratulations—you got top grades!” Aunt Zihriya beamed at me.

I got really angry and refused to accept the certificate. “I didn’t earn this and I don’t want it,” I said, stomping.

“Who gets full marks and gets mad?” Aunt Zihriya asked in surprise.

“Me!”

Dad retold the story so many times that we could never forget it. He’d bring it up at just the right time to make a point.

“Real success is earned through hard work,” he said. And he turned his head to lock eyes with each of his four children, one at a time.