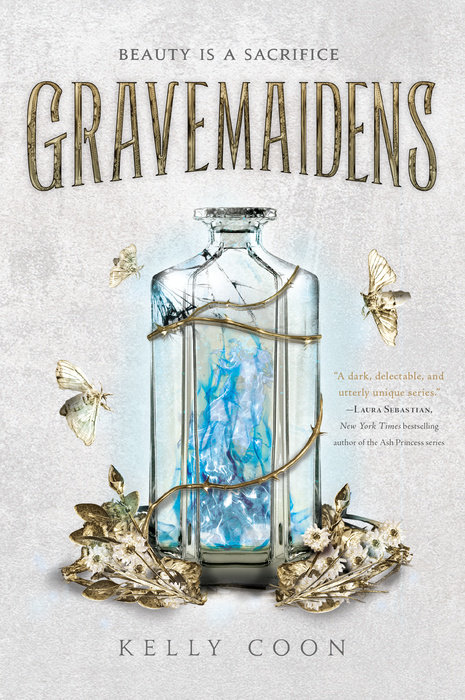

Gravemaidens

“A dark, delectable, and utterly unique series that readers will want to drown in.” —Laura Sebastian, New York Times bestselling author of the Ash Princess series

The start of a fierce fantasy duology about three maidens who are chosen for their land's greatest honor...and one girl determined to save her sister from the grave.

In the walled city-state of Alu, Kammani wants nothing more than to become the accomplished healer her father used to be before her family was cast out of their privileged life in shame.

When Alu's ruler falls deathly ill, Kammani’s beautiful little sister, Nanaea, is chosen as one of three sacred maidens to join him in the afterlife. It’s an honor. A tradition. And Nanaea believes it is her chance to live an even grander life than the one that was stolen from her.

But Kammani sees the selection for what it really is—a death sentence.

Desperate to save her sister, Kammani schemes her way into the palace to heal the ruler. There she discovers more danger lurking in the sand-stone corridors than she could have ever imagined and that her own life—and heart—are at stake. But Kammani will stop at nothing to dig up the palace’s buried secrets even if it means sacrificing everything…including herself.

"A dark and utterly enthralling journey to an ancient land, Gravemaidens grabs you by your beating heart and refuses to let go until the bitter, breathtaking end."—Sarah Glenn Marsh, author of the Reign of the Fallen series

An Excerpt fromGravemaidens

Today, three girls would be doomed to die an honored, royal death.

A coil of dread wound itself around my guts at the thought, but I took a deep breath and focused on the little boy standing in front of me. Getting wrapped up in Palace rituals wasn’t part of my duties, but healing a child was.

Especially when his cure meant food for my family.

“Open your mouth and say ‘Ahhh’ as if the Boatman were chasing you.” I held his face, which was covered in crumbs. Probably the remnants of a thick slice of warm honeycake. My stomach rumbled, imagining the treat he’d likely enjoyed. Beneath the sticky mess, his tawny cheeks were unusually pale.

“Ahhhhhh!” the boy screamed.

Smiling slightly, his innocence a welcome relief from my dark thoughts, I stuck the end of a spoon into his mouth to hold down his tongue, angling his head to the morning sunlight to see inside. Behind me, his mother hovered, smoothing her violet tunic and patting her hair, which was fastened into two neat buns above her ears. When she fidgeted, the gold chains looped around her forehead shimmered in the light streaming in from the window.

Despite the circumstances, it was nice to see that the mothers who had all the wealth in the city were no different from the mothers in my neighborhood who had none. When it came to their sick children, their hands twisted nervously in the same way.

The boy’s throat was blistered white. I smoothed my hands over his bare back and touched my lips to his forehead to check for fever--an old healer’s trick, since lips are more sensitive than hands. He was slightly warm but not worryingly so. The glands in his neck were swollen, as they should be with an infection, but this child would be able to fight it off. His muscles were strong, his reflexes good, his eyes clear. Unlike the children of my neighbors, he was undoubtedly fed daily with the freshest fruits and vegetables, the finest fish and meats. I swallowed my hurt at the inequity.

But it wasn’t this child’s fault.

“You’re going to be just fine.” I ruffled his silky hair.

“I am?” He popped his thumb in his mouth and sucked furiously, then withdrew it when his mother looked sideways at him with eyes outlined by thick strokes of kohl. “Are you sure?”

“Of course I’m sure!” I took his chin in my palm. “Why do you ask?”

“Because the Boatman comes when you’re really sick.” His lip trembled, and the thumb went back into his mouth.

I took his other hand in mine. “I’m sorry if I scared you when I mentioned the Boatman. The truth is, he’s not so scary at all. He’s a helper to the gods. Did you know that?”

The lie rolled effortlessly off my tongue.

He shook his head.

“It’s true. The Boatman is just a man who lived long ago.” I looked around the common room for something to add a note of truth to my tale. A carved-wood sicklesword, one that was, no doubt, modeled after his guardsman father’s, sat atop a braided rug next to an emerald-colored floor cushion. “The Boatman used to be a guardsman. But now he’s a helper. When you die, you pay the coin for your passage and the Boatman scoops you up, puts you into his rickety boat, and paddles you off to the Netherworld, where there are endless parties and games and honeycake forever and ever.”

I squatted down to his eye level. “But he only comes if you’re very, very sick--which you are not--or very, very old--which you are not, although you do look much older than you are with these big, strong muscles.” I squeezed his little arm.

He giggled around the thumb in his mouth. Then his eyes grew serious. “Will Ummum be there in the Netherworld when I go?” He looked at his mother, who ran her clean, carefully tended fingernails down her arm. From the direction of the sleeping quarters, an infant wailed.

“Yes. Before you go with the Boatman as an old, old, old man”--the smile flickered again--“she will be there waiting for you with the biggest honeycake of all.”

My throat constricted as I finished the story, but I forced the sorrow away with every bit of my strength.

I stood and turned to his mother. “Do you have any garlic?”

“Let me check with the servant.” She called into the other room. “Hala?”

A girl my sister’s age--maybe fifteen years--appeared in the doorway, holding the squalling infant in her arms. She was the child of one of my neighbors. Women of my stature often sent their unmarried daughters to be servants in other people’s households to earn coins or food. “My lady?” she said, her eyes on her bare feet.

“Where is the garlic?”

“It’s in the bin near the door. Shall I fetch it for you?”

“Why do you suppose I asked for it?” The woman crossed her arms over her chest. Hala dipped her head, her cheeks blazing, and retreated with the infant.

I took a breath, forcing myself to put on the mask of civility I wore daily when dealing with the ill and their families. “To help ease his throat and take away the infection, mix six crushed cloves in a flagon of warm water and bid him gargle with it.”

She nodded her agreement. “He won’t like it, but if it will help, we will do it.”

“Yes, and it will have to be twice a day for three days. By the end of the third day, if his symptoms persist, send for me again and I will bring a stronger tincture.”

“Okay. Thank you, A-zu.” She turned, as if to go.

“Oh, no, my lady. I am no great A-zu. My abum is the best healer in the city.” No matter what anyone thinks anymore. “I am merely his apprentice.”

“Well, then why didn’t he come himself? Why did he send you?” She looked me up and down.

Why didn’t I keep silent?

I stared at my dirty toes, encased in sandals that were two years too small. There was no easy way to answer her question. When my mother had passed away a moon ago, he’d lost his will to tend to himself, let alone anyone else. Not only had I taken on the tasks of running the household and caring for my sister, but I’d also been visiting his patients all over the city. As his healer’s apprentice, it was my duty. Plus, we had to get paid.

“He was called away for an emergency, my lady, but I’d be happy to send him when he is back if you need him.”

I was making a promise I might not be able to keep, but the coins were already in her hand. If she opted not to pay me, there was nothing I could do, and I had to take care of my family.

She blew out an exasperated breath, then looked back at her little boy, who was squatting on the rug, playing with the sicklesword. “Fine,” she murmured. “Take this and be gone.”

She dropped six shekels into my hand, pulling away quickly, as if I were the one with an illness. I stuffed them into my healing satchel before she could change her mind.

“Thank you, noblewoman. I appreciate your generosity.” I nodded once to the boy and then to Hala, who’d come back with the garlic and the red-faced baby. Right before I closed the door, the woman snatched the garlic from Hala’s hand and yelled at her for not moving faster. I cringed, thinking of my own sister taking a scolding like that, as I headed quickly toward the marketplace. Thankfully, with the healing practice, I hadn’t yet needed to subject her to a wealthy woman’s whims. I shook my head at poor Hala’s fate.

Such was life for those born low and for those like us, cast into poverty after the biggest regrets of our lives.

At least now I had the means to buy grain and could be out of the marketplace before three perfectly healthy girls were called upon to lie in the cold embrace of a dead ruler.