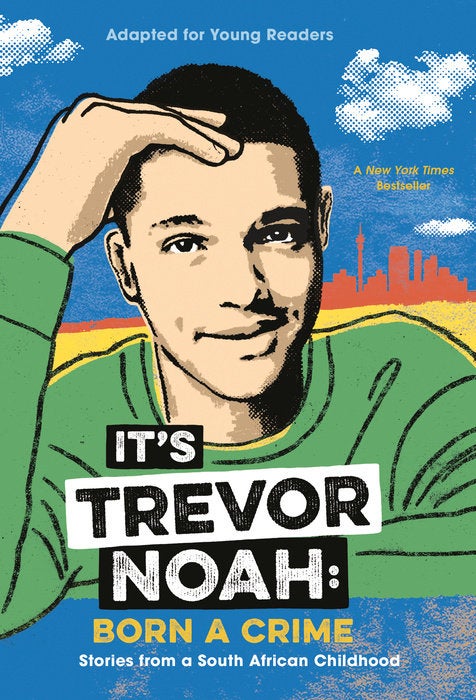

It's Trevor Noah: Born a Crime

Stories from a South African Childhood (Adapted for Young Readers)

A New York Times Bestseller

The host of The Daily Show, Trevor Noah, tells the story of growing up half black, half white in South Africa under and after apartheid in this young readers' adaptation of his bestselling adult memoir Born a Crime: Stories from a South African Childhood.

BORN A CRIME IS SOON TO BE A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE STARRING OSCAR WINNER LUPITA NYONG'O!

Trevor Noah, the funny guy who hosts The Daily Show on Comedy Central, shares his remarkable story of growing up in South Africa with a black South African mother and a white European father at a time when it was against the law for a mixed-race child to exist. But he did exist--and from the beginning, the often-misbehaved Trevor used his keen smarts and humor to navigate a harsh life under a racist government.

This fascinating memoir blends drama, comedy, and tragedy to depict the day-to-day trials that turned a boy into a young man. In a country where racism barred blacks from social, educational, and economic opportunity, Trevor surmounted staggering obstacles and created a promising future for himself, thanks to his mom's unwavering love and indomitable will.

It's Trevor Noah: Born a Crime not only provides a fascinating and honest perspective on South Africa's racial history, but it will also astound and inspire young readers looking to improve their own lives.

Click the image below to download the Born a Crime Discussion Guide:

An Excerpt fromIt's Trevor Noah: Born a Crime

I was nine years old when my mother threw me out of a moving car.

It happened on a Sunday. I know it was on a Sunday because we were coming home from church, and every Sunday in my childhood meant church. We never missed church. My mother was--and still is--a deeply religious woman. Very Christian. Like indigenous peoples around the world, black South Africans adopted the religion of our colonizers. By “adopt,” I mean it was forced on us.

My childhood involved church, or some form of church, at least four nights a week. Tuesday night was the prayer meeting. Wednesday night was Bible study. Thursday night was youth church. Friday and Saturday we had off. Then on Sunday we went to church. Three churches, to be precise. The reason we went to three churches was because my mom said each church gave her something different. The first church offered jubilant praise of the Lord. The second church offered deep analysis of the scripture, which my mom loved. The third church offered passion and catharsis; it was a place where you truly felt the presence of the Holy Spirit inside you. Completely by coincidence, as we moved back and forth between these churches, I noticed that each one had its own distinct racial makeup: Jubilant church was mixed church. Analytical church was white church. And passionate, cathartic church, that was black church.

Mixed church was Rhema Bible Church. Rhema was one of those huge, supermodern, suburban megachurches. The pastor, Ray McCauley, was an ex-bodybuilder with a big smile and the personality of a cheerleader. Pastor Ray had competed in the 1974 Mr. Universe competition. He placed third. The winner that year was Arnold Schwarzenegger. Every week, Ray would be up onstage working really hard to make Jesus cool. There was arena-style seating and a rock band jamming with the latest Christian contemporary pop. Everyone sang along, and if you didn’t know the words that was okay because they were all right up there on the Jumbotron for you. It was Christian karaoke, basically. I always had a blast at mixed church.

White church was Rosebank Union in Sandton, a very white and wealthy part of Johannesburg. I loved white church because I didn’t actually have to go to the main service. My mom would go to that, and I would go to the youth side, to Sunday school. In Sunday school we got to read cool stories. Noah and the flood was obviously a favorite; I had a personal stake there. But I also loved the stories about Moses parting the Red Sea, David slaying Goliath, Jesus whipping the money changers in the temple.

I grew up in a home with very little exposure to popular culture. My mom didn’t want my mind polluted by sex and violence. The only music I really knew was from church: soaring, uplifting songs praising Jesus. It was the same with movies. The Bible was my action movie. Samson was my superhero. He was my He-Man. A guy beating a thousand people to death with the jawbone of a donkey? That’s pretty fierce. Eventually you get to Paul writing letters to the Ephesians and it loses the plot, but the Old Testament and the Gospels? I could quote you anything from those pages, chapter and verse. There were Bible games and quizzes every week at white church, and I always trounced everyone.

Then there was black church. There was always some kind of black church service going on somewhere, and we tried them all. In the township, that typically meant an outdoor, tent-revival-style church. We usually went to my grandmother’s church, an old-school Methodist congregation, five hundred African grannies in blue-and-white blouses, clutching their Bibles and patiently burning in the hot African sun. Black church was rough. No air-conditioning. No lyrics up on Jumbotrons. And it lasted forever, three or four hours at least, which confused me because white church was only like an hour--in and out, thanks for coming. But at black church I would sit there for what felt like an eternity, trying to figure out why time moved so slowly. I eventually decided black people needed more time with Jesus because we suffered more.

Black church had one saving grace. If I could make it to the third or fourth hour I’d get to watch the pastor cast demons out of people. People possessed by demons would start running up and down the aisles like madmen, screaming in tongues. The ushers would tackle them, like bouncers at a club, and hold them down. The pastor would grab their heads and violently shake them back and forth, shouting, “I cast out this spirit in the name of Jesus!” Some pastors were more violent than others, but what they all had in common was that they wouldn’t stop until the demon was gone and the congregant had gone limp and collapsed on the stage. The person had to fall. Because if he didn’t fall that meant the demon was powerful and the pastor needed to come at him even harder. You could be a linebacker in the NFL. Didn’t matter. That pastor was taking you down. Good Lord, that was fun.

Christian karaoke, fierce action stories, and violent faith healers--man, I loved church. The thing I didn’t love was the lengths we had to go to in order to get to church. It was an epic slog. We lived in Eden Park, a tiny suburb way outside Johannesburg. It took us an hour to get to white church, another forty-five minutes to get to mixed church, and another forty-five minutes to drive out to Soweto for black church. Then, if that wasn’t bad enough, some Sundays we’d drive back to white church for a special evening service. By the time we finally got home at night, I’d collapse into bed.

This particular Sunday, the Sunday I was hurled from a moving car, started out like any other Sunday. My mother woke me up, made me porridge for breakfast. I took my bath while she dressed my baby brother, Andrew, who was nine months old. Then we went out to the driveway, but once we were all strapped in and ready to go, the car wouldn’t start. My mom had this ancient, broken-down, bright-tangerine Volkswagen Beetle that she picked up for next to nothing and it was always breaking down. To this day I hate secondhand cars. I’ll take a new car with the warranty every time. As much as I loved church, taking public transport meant the slog would be twice as long and twice as hard. When the Volkswagen refused to start, I was praying, Please say we’ll just stay home. Please say we’ll just stay home. Then I glanced over to see the determined look on my mother’s face, her jaw set, and I knew I had a long day ahead of me.

“Come,” she said. “We’re going to catch minibuses.”