It was the first Sunday of summer break, and I was in a hurry to finish my dusting chores fast so I could call Khalfani to ride bikes. I wasn’t even thinking too hard about anything, like Dad says I do sometimes.

Well, okay, maybe I was thinking a little bit hard. About Grampa Clem and how I’m going to miss fishing with him this summer. Which made me think about the funeral and how the man in the black robe had said, “From dust we come and to dust we shall return.” And then I started looking more closely at the gray particles I was picking up with my dust rag, and I thought, What is this stuff anyway? And where does it come from? And how come it keeps coming back no matter how many times I wipe it away?

That’s when the science part of me took over.

I stopped thinking about Khalfani and riding my bike, and even Grampa Clem. And I definitely wasn’t thinking about finishing any chore. I went straight to my…

It was the first Sunday of summer break, and I was in a hurry to finish my dusting chores fast so I could call Khalfani to ride bikes. I wasn’t even thinking too hard about anything, like Dad says I do sometimes.

Well, okay, maybe I was thinking a little bit hard. About Grampa Clem and how I’m going to miss fishing with him this summer. Which made me think about the funeral and how the man in the black robe had said, “From dust we come and to dust we shall return.” And then I started looking more closely at the gray particles I was picking up with my dust rag, and I thought, What is this stuff anyway? And where does it come from? And how come it keeps coming back no matter how many times I wipe it away?

That’s when the science part of me took over.

I stopped thinking about Khalfani and riding my bike, and even Grampa Clem. And I definitely wasn’t thinking about finishing any chore. I went straight to my computer and got on the Internet, where I typed in the search question “What is dust?”

Sixty-seven million, nine hundred thousand results came up.

I had no idea there would be so much out there about dust, but that’s the thing about asking questions: They often lead to surprises, and they always lead to more questions.

I climbed our table to get a sample from the candelabra-thingy (it was the dustiest place I could think of in our house, since I never dust it), and went to my room. I set the microscope slide on my desk and pulled out the spiral notebook I keep between my bed and the wall.

Across the yellow cover, I had written in big black letters, confidential. Dad taught me how to spell it. He’s a police detective, so he knows all about confidential things. confidential says that what’s inside is important. Plus, you never know when you might discover something that really is top-secret.

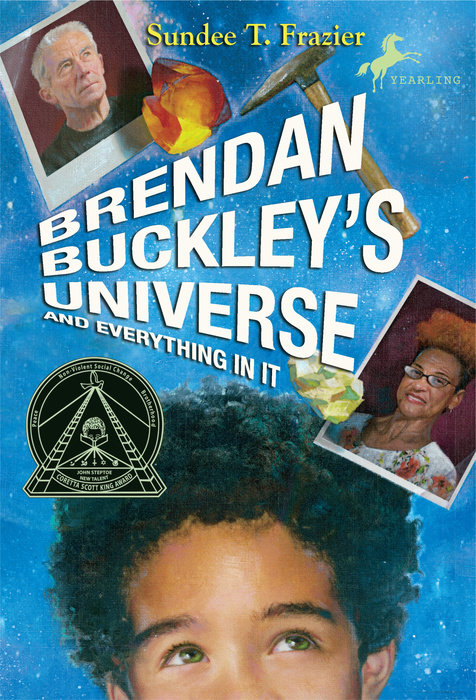

I sat at my desk and flipped open the cover. The question notebook was my fifth-grade teacher’s idea, but the name for the notebook was mine: Brendan Buckley’s Book of Big Questions About Life, the Universe and Everything in It.

“Scientists,” Mr. Hammond had said at the beginning of the school year, “ask questions.”

That’s when I knew: I am a scientist. Because as far as I’m concerned, no question is unimportant, and nothing in the universe is too small to ask about.

I ran my hand across my book’s title. Summer vacation had finally arrived. That meant seventy-nine days to find answers to the questions I’d already recorded. Seventy-nine days of scientific experimentation. And seventy-nine days to mess around with Khalfani, swim in his pool and get to the next level in Tae Kwon Do. Khal and I are only five ranks away from our black belts.

The thing I wouldn’t be doing was fishing every Monday with Grampa Clem. When Grampa Clem died in April, it was sort of like having my leg taken away. You always expect it to be there, but then to one day wake up and find it gone? Suddenly everything’s different and there’s nothing you can do about it.

Now Gladys is my only grandparent, because my other grandma died right after I was born and I’ve never met my other grandpa. Mom doesn’t talk to him. Or about him, either, which makes me wonder what happened. But I guess I can’t miss someone I’ve never even known.

The one time I asked where he was, she bit on her lip, and her forehead bunched up like when she cut her thumb and had to get stitches. She just said, “Gone,” and that we’d talk about it when I was older. So that’s the One Thing I know not to ask questions about.

I turned to the front section of my notebook, which I’d titled The Questions. The back section was called What I Found Out. Under “Do centipedes really have 100 legs?”, “What’s inside a black hole?” and “Do boys fart more than girls?” I wrote my latest questions about dust.

Mr. Hammond told us that scientists’ questions compel them to find answers, and that’s how they make their discoveries. I asked Mr. Hammond what being compelled meant, and when he said it meant to have an uncontrollable urge that won’t be satisfied until you find what you’re looking for, I knew exactly what he was talking about. I get compelled all the time.

I ran to the bathroom with an eyedropper from my microscope kit and suctioned some water from the faucet. I went back to my room, squeezed a couple of drops onto the slide and pressed another slide on top. I stuck the dust under the lens.

The cool thing about my scope is that it displays whatever it’s looking at on my computer. I clicked a couple of times to open the program and up popped my dust--magnified four hundred times.

It was basically a bunch of small flakes. But flakes of what? I opened an Internet article called “Dust Creatures” and started reading.

The article said when you examine household dust under a microscope you can usually spot ant heads or other insect body parts. I had just clicked over to my microscope display to look for bug legs when a car door slammed outside.

I glanced out the window. Dad was back with my grandma, Gladys. A minute later the front door opened.

“I’m here!” Gladys shouted.

I got up to say hi because I wasn’t seeing any bug parts, and because any minute Gladys would show up in my room anyhow. Gladys doesn’t pay attention to my EXPERIMENT IN PROGRESS sign.

I stood at the top of the stairs that go down to the front door. Gladys was bent over, pulling off her shoes.

“These bad boys got to go!”

Dad tried to squeeze in behind her.

Gladys looked at him over her shoulder with her eyebrows raised. “Where’s the fire?”

Mom says that Gladys can be testy, like a bull that’s been prodded one too many times. Gladys’s nostrils were flared. I could almost see the long horns coming out the sides of her head. Dad was about to get it.