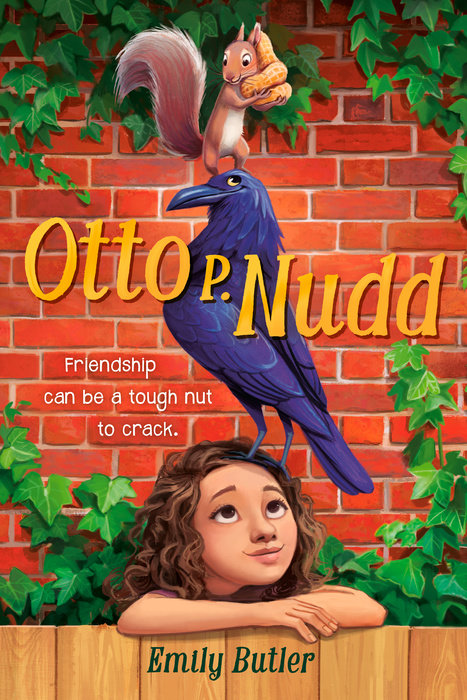

Otto P. Nudd

Author Emily Butler

Fans of The Tales of Despereaux, Pax, and Crenshaw will delight over this friendship story about a brash raven, a dutiful squirrel, and the human girl that brings them together. The perfect read for animal lovers.

Otto P. Nudd: Tthe BEST bird in Ida Valley (at least according to him). While his buddies waste their days at the dump cracking jokes, Otto invents things with his human neighbor Old Man Bartleby in their workshop.

Marla: The Competition. This protective mama-squirrel will swipe Otto's snacks from under his beak if it means another meal for her babies!

Pippa: The girl who loves the birds in Ida Valley, and Otto most of all. But when Bartleby''s latest contraption lands him in danger, the whole neighborhood--kids and critters alike--will have to join forces to save their oldest friend!

Author Emily Butler delivers a timeless friendship tale about a brash raven, a crafty squirrel, and the neighborhood that brings them together.

An Excerpt fromOtto P. Nudd

1

A Man, a Raven, and a Thingamajig

“Otto, you’re splendid,” mumbled Bartleby Doyle. “You’re a genius. A bird for the ages.”

His mouth was full of pins and it was hard to make out every word, but Otto had a good idea of what he was saying. If a raven could blush, Otto would have blushed. But not because he disagreed with Bartleby. Oh, no. The Old Man was right.

“The likelihood of this thingamajig going up in flames is small,” continued Bartleby. “But why take a chance if you don’t have to?”

Otto winced. He disliked the word “thingamajig,” preferring “machine,” or even “contraption.” But he was fussier than the Old Man, who was (for the greatest inventor Ida Valley had ever known) a casual, absentminded sort of human.

Bartleby bent over the length of moss-colored corduroy and pinned a strip of white fabric to it. The fabric was fireproof. It was, in fact, cut from the underwear of Ida Valley’s fire chief. Bartleby never asked how Otto had obtained this item, but you should know that (1) it…

1

A Man, a Raven, and a Thingamajig

“Otto, you’re splendid,” mumbled Bartleby Doyle. “You’re a genius. A bird for the ages.”

His mouth was full of pins and it was hard to make out every word, but Otto had a good idea of what he was saying. If a raven could blush, Otto would have blushed. But not because he disagreed with Bartleby. Oh, no. The Old Man was right.

“The likelihood of this thingamajig going up in flames is small,” continued Bartleby. “But why take a chance if you don’t have to?”

Otto winced. He disliked the word “thingamajig,” preferring “machine,” or even “contraption.” But he was fussier than the Old Man, who was (for the greatest inventor Ida Valley had ever known) a casual, absentminded sort of human.

Bartleby bent over the length of moss-colored corduroy and pinned a strip of white fabric to it. The fabric was fireproof. It was, in fact, cut from the underwear of Ida Valley’s fire chief. Bartleby never asked how Otto had obtained this item, but you should know that (1) it was scrupulously clean, and (2) the fire chief never left a basket of laundry unattended on the roof of his car again. At any rate, when Otto had pressed a flaming match to the garment and it had refused to ignite, Bartleby bought an entire case of underwear. Then they’d cut it all into the strips that now lay on the workbench.

Bartleby held out his hand. Otto gave him a strip, and then another, and another. Eventually, the corduroy was covered with overlapping white strips. Bartleby carried everything to a sewing machine under a long, high window through which the gray light of dawn shone, and sat down.

While the Old Man fiddled with the stitch length regulator, Otto looked about their workshop with immense satisfaction. They had all the good stuff. There were table saws of many kinds, and a drill press, and chests full of wrenches and screwdrivers. There were buckets of bolts, jars of nails, and a vast array of pulleys and gears. There were also many finer instruments, like strain gauges, flowmeters, and gadgets to measure acceleration and isolate vibrations. A water fountain dominated an entire corner of the shop, used by man and raven alike whenever they got thirsty. Otto loved that thing!

What couldn’t a person (or bird) invent here?

Two details seemed out of place in the workshop. An empty birdcage protruded from behind some filing cabinets, and large burlap sacks bulging with peanuts were lined up against a wall, slumping over a little, as if they were taking a nap. Neither were items of curiosity to Otto. He had lived in the cage, and knew the nuts were part of a monthly delivery that had been going on since before he’d hatched.

The fact was that Bartleby was a peanut fanatic. He fed them to corvids, as we shall see, and he popped them into his own mouth like candy.

“Ready, my boy?” asked Bartleby.

Otto positioned himself on the other side of the sewing machine and gave Bartleby the smallest of nods. Without another word, the Old Man rammed his foot down on the floor pedal.

The machine jolted to life. Its needle gobbled through the fabric like a noisy demon, suturing the layers of cloth together faster and faster. Bartleby barely kept up with it, guiding the material over the feed dogs and back to Otto. The raven deftly plucked the pins out of the fabric as they passed him, thrusting each one into a round pincushion. He didn’t miss any.

They made an excellent team.

When they were done, Bartleby shook the corduroy out and examined it for gaps between the seams. There were none. Otto checked it a second time, going over every stitch with eyes as keen as blades. Their work was good. It was more than good--it was super. Otto flew to Bartleby’s shoulder and balanced there, imperious and bright. “Hello!” he cawed. “Hello!”

Deep, happy wrinkles puckered Bartleby’s face. He stroked the exuberant ruff of feathers under Otto’s throat as he walked to the door of their workshop. They would meet again after breakfast.

“We’re ready, old bean,” he said (even though Otto was a young bean). “Very, very ready. I can feel it in my bones. Today’s the day.”

2

The Inside Scoop

Pippa Sinclair stomped into the kitchen. She looked absolutely ferocious.

“Where’s my yellow scoop? I can’t find it anywhere. And I’ve turned the house inside out!”

“Turned the house inside out?” Mrs. Sinclair looked up from her list, the first of many she would scribble that day. “You just rolled out of bed.”

“Where’s my yellow scoop?” Pippa would not be sidetracked.

“I borrowed it a tiny bit,” admitted Mrs. Sinclair. She knew she was guilty. “Just to plant the pansies. It’s in the bag of garden soil.”

Pippa stared at her mother in disbelief. “You mean the dirt?” she asked. “Mom, that scoop is strictly off-limits.”

Mrs. Sinclair stared back at Pippa, their eyes locked in a contest of wills. Then Mrs. Sinclair surrendered. Pippa was formidable even when she was wrong. When she was right, she towered with moral authority.

“Off-limits!” repeated Pippa. “It’s for the birds, and the birds only.”

“It’s for the birds,” Mrs. Sinclair conceded, waving her list in defeat.

Pippa threw open the doors to the porch overlooking the backyard. There, by a clump of purple pansies, was the bag of garden soil. And sure enough, a yellow plastic handle emerged from its loamy surface.

“Not cool, Mom,” said Pippa.

She sped outside, yanked the scoop out of the soil, and rapped it against the porch a little harder than was necessary. Then she unscrewed the lid on the five-gallon bucket of premium birdseed that she kept in the shade of a lilac bush. It was the delicious kind, with extra sunflower kernels. Pippa plunged the scoop into its depths several times, filling a mason jar with the blend of nuts, seeds, and dried berries. Then she carried the jar across the yard and set it at the base of the bird feeder.

Now came the hard part. The bird feeder hung six feet in the air, and Pippa was shrimpy, even for a ten-year-old. She used a long branch that forked at the tip to lift the feeder off its pole. After lowering it to the ground, she filled its hopper with birdseed from her jar. Then she hoisted it all the way back up. Her arms shook with effort.

“Come and get it!” she yelled.

She didn’t wait to see who was going to show up first. She was running behind schedule, and there was still the question of Otto’s gift.

Was anyone watching? She didn’t think so.

Pippa sidled over to the Japanese maple whose long branches brushed the dirt like gentle brooms. It offered good cover. She ducked under the leaves and put out a hand, touching the place where two roots met to form a little bowl. Yes, something was there--a hard, smooth, narrow thing, which Pippa slipped into the pocket of her jeans.

From her other pocket, she pulled out half a hamburger she’d saved from yesterday’s dinner. It was squashed from spending the night in her sock drawer. Otto won’t care, she thought. He’s not picky. She put it in the spot between the roots and backed away, emerging from the tree and wiping her palms on her shirt.

“Hello, Otto! Hello!” she shouted into the woods behind her house.

Now Pippa was just plain late. Mr. Doyle, her next-door neighbor, was probably waiting for her.

“Eat something. Eat a muffin, at least,” nagged Mrs. Sinclair as Pippa whizzed back through the kitchen.

There was no time to eat a muffin. She’d chew a handful of birdseed on the way to school. Some days were like that. But she couldn’t leave the house without checking her treasures.

Pippa ran up to her bedroom and pulled a fishing tackle box from under her bed. She flipped the lid open, and there they were, the things Otto had left for her under the tree. Each treasure was in its own compartment. There was a large assortment of buttons, both brass and plastic. There was a bracelet with a broken clasp, and a silver charm shaped like a sailboat. There was a new tube of ChapStick and several bottle caps. Paper clips and polished rocks and a lens from a pair of sunglasses. Clamshells and a green foam dart and three dimes. Nuts and bolts fused together with orange rust. An earring.

Pippa reached into her pocket and pulled out this morning’s gift.

“Oh,” she breathed. “Oh, Otto. It’s sublime.”

She stroked the flawless curve of a white porcelain handle with her fingertip. It still had some of the teacup attached. It was sublime.

3

Folks Oughta Mind Their Own Business

Otto P. Nudd was raised in captivity, but by dint of hard work and shrewdness, he was now a free bird. “A true raven will not be shackled” was his personal slogan, and he repeated it now as he tiptoed into his own home.

“You mean the way I’m shackled to this thing?” asked Lucille from the far side of the living room.

Otto jumped. He hadn’t realized she was awake and rocking the incubator like a crib. Was she teasing him? Otto thought so but wasn’t a hundred percent sure. They were practically newlyweds, and he was still getting used to her playfulness.

Lucille gave him a reassuring roll of her black eyes, and he relaxed.

“How’d you sleep, dear?” she inquired. “You left before the sun was up.”

“I slept well, thank you,” he said.

Otto was an early bird by nature. What Lucille didn’t know was how many predawn hours her husband spent with the Old Man, himself an early riser. Frankly, she didn’t know because Otto didn’t tell her. He wasn’t sure she’d appreciate how much time he spent in the workshop inventing things, now that they were expecting their first chick.

Of course, Lucille understood that Otto was an inventor. That was no secret. Theirs was an uncommonly fine nest--Lucille knew just how fine it was, because she had built it herself--but Otto was the one who had filled it with all sorts of devices of his own making. He was an inventor of many things, and she loved that about him.

Now he sat on the couch and flipped through the issue of Popular Science he’d fished out of a dumpster behind the ShopRite. Why humans threw away such prizes he’d never know! He particularly liked the article about motor oil filtration, and had read it many times.

“ ‘Sludge will destroy an engine,’ ” he murmured to himself, turning the page.

“Down with sludge!” agreed Lucille.

She stepped lightly on a spring-loaded trapdoor in the floor of their nest, and it popped open with a whoosh. A hole was revealed, and through it, she kicked some shriveled grapes and an onion ring, remnants of last night’s meal. Lucille did not care for leftovers. She closed the door and covered it with a straw mat.

“What are your plans for the day, my love?” she asked.

“Oh, just the usual. Making sure the neighborhood isn’t going to heck in a handbasket--that sort of thing.” Otto did not mention the Great Experiment that was to take place behind the workshop later that morning. He should have, but he didn’t. “What are your plans for the day?”

“Hmmm,” she said slowly, as if giving the question her full consideration. “The first thing I’m going to do is find a bird who knows a thing or two about fixing incubators.”

When this failed to elicit a response, she persevered. “Because our incubator is on the fritz. The fritz! At this rate, I’m going to have to sit on our egg myself.”

Otto was engrossed in an advertisement for double-handle wrenches.

“Maybe I’ll take a crack at it,” said Lucille. “I know a thing or two about vices.”

“Devices. De-vices. Never call them ‘vices,’ for that is what they are not.” Otto sighed and closed the magazine. “Now, what are you going to crack?”

“The incubator, dear. Our egg is cooling down.”

Seventeen days ago, Lucille had carefully deposited an egg into the incubator, designed and built by Otto. Other birds sat on their eggs, never leaving an unhatched brood for longer than a few minutes. Lucille was far too modern to adopt that practice. Still, she turned the egg every quarter hour, and it was getting cold. No ifs, ands, or buts about it.

“Impossible,” said Otto.

He crossed the nest to examine the large box built out of plywood scavenged from the town dump. It sat on four sturdy legs and featured a viewing window. With a simple twist of a crank, an adjustable shelf within the box tilted back and forth, allowing the egg to be turned. (An unturned egg, it was felt, would result in an addlebrained chick, and Otto was having none of that.) The most remarkable part of the contraption was its side-mounted boiler, filled with water and heated by a small kerosene lamp. Once heated, the water was piped around the inside of the box, keeping the egg nice and toasty.

An open flame was, ordinarily, the last thing a raven would allow inside her nest. Indoor heating was an abomination to all birds, despised by even the most stupid. Only after Otto demonstrated the flameproof properties of the box a hundred times (it was lined with the same stuff he’d introduced to the Old Man) would Lucille consent to having it in her home. And now she could not do without it.

Otto saw the problem at once. He lifted the top off the box and adjusted the pipes. “All better now,” he said to the egg, giving it a gentle nudge with his head in what he hoped was a paternal manner. Was this what a father would do? He guessed it might be, but he wasn’t sure.

How did one act “fatherly,” anyway? It wasn’t as if the egg had come with an owner’s manual, and Popular Science was strangely silent on the issue. Life would be different when the egg hatched, and the thought unnerved him. He might not do everything right. He might not do anything right. Well, the chick would show itself soon enough, and then he’d figure things out in the privacy of his own nest.

Or would he? To Otto’s annoyance, their brood of one was enormously interesting to the neighborhood. It was practically turning into a community event.

“Folks oughta mind their own business,” he told the egg.

“Why? It’s an egg like no other!” cried Lucille stoutly.

“We should charge admission,” Otto grumbled.

The egg was a full 50 percent larger than average. It was undeniably a raven egg, oblong and a mottled blue. But it was huge. Otto had never seen anything like it. Neither had their neighbors, who took every opportunity to cram themselves into the nest and goggle at the thing. It was a miracle, they said! It was a sign of the times!