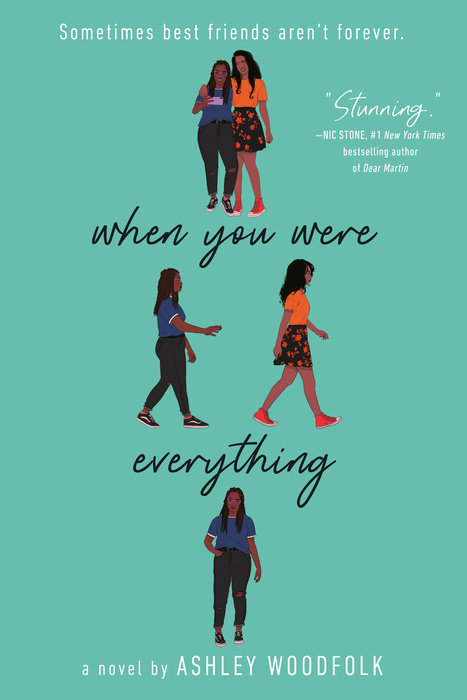

When You Were Everything

For fans of Nina LaCour's We Are Okay and Adam Silvera's History Is All You Left Me, this heartfelt and ultimately uplifting novel follows one sixteen-year-old girl's friend breakup through two concurrent timelines--ultimately proving that even endings can lead to new beginnings.

"Stunning." --Nic Stone, bestselling author of Dear Martin and Odd One Out

You can't rewrite the past, but you can always choose to start again.

It's been twenty-seven days since Cleo and Layla's friendship imploded.

Nearly a month since Cleo realized they'll never be besties again.

Now Cleo wants to erase every memory, good or bad, that tethers her to her ex-best friend. But pretending Layla doesn't exist isn't as easy as Cleo hoped, especially after she's assigned to be Layla's tutor. Despite budding friendships with other classmates--and a raging crush on a gorgeous boy named Dom--Cleo's turbulent past with Layla comes back to haunt them both.

Alternating between time lines of Then and Now, When You Were Everything blends past and present into an emotional story about the beauty of self-forgiveness, the promise of new beginnings, and the courage it takes to remain open to love.

"Breathtakingly beautiful....Woodfolk has a way of making words sing and burst with light." --Tiffany D. Jackson, award-winning author of Monday's Not Coming and Let Me Hear A Rhyme

An Excerpt fromWhen You Were Everything

A Theory & A Snowman

When the train finally shows up, it’s so crowded that I end up smashed into a corner between a stroller and the doors, and the guy in front of me is wearing a backpack he refuses to take off. One of the buckles is pressing against my boob.

I want to growl at this guy to put his bag on the floor, for everyone to give me some goddamn space, but I don’t, because I don’t do stuff like that. If Layla were here, she’d tell the dude off.

But she isn’t! I shout inside my own head. For fuck’s sake, stop torturing yourself.

So I imagine a clean sheet of paper. Mentally, I start making the list I need to rid myself of thoughts like these. The steps I need to take to rid myself of Layla . . . for good. The systematic way I’m going to unhaunt my whole life.

I get off a few stops later when we reach Layla’s station--the one where she’d hop on the train every morning and find me. I’d always sit in the first car so she’d know to walk to the front of the platform to wait. When the train pulled in, I’d look for the smear of her black hair, or the blur of her hand as she waved at me. We met and rode to school every day that way.

I follow the flow of bodies toward the stairwell, push my way through the turnstile, and step out onto the sidewalk. I slip my earbuds back in, put on Ella Fitzgerald, and look left and right, making sure no one who knows me is around. The coast looks clear, so I turn my music up, cross my fingers, and keep moving. Something about skipping school makes me feel like I’m actually in control of my life.

I walk down Layla’s block, taking in all the familiarities of the street. The way the door to the bodega on the corner doesn’t close all the way. The ragged rainbow flag hanging from the fire escape of the building beside hers. The same yellowed flyer’s been taped in the window of the deli advertising their “new” kosher salami since I was twelve.

We always got Popsicles at that bodega in the summer. We challenged each other to jump and touch the hanging threads of that flag whenever we walked past it. We never tried the salami, but we’d get sandwiches and ninety-nine-cent Arizona iced teas at the deli almost every time I slept over. If it was warm out, we’d eat on Layla’s stoop.

I keep walking, past Layla’s building and into the park where we first met. Its lawn is wide and still a little green even though it’s February. The grass is dusted with snow and it’s still falling fast. I go to the exact spot where I was sitting the day I met Layla--the exact spot where she saw me crying about Gigi and where she started singing to make me feel better--and I text my dad.

Daddio, I send. You’re off today, right?

His response comes almost instantly. Yep.

Can you meet me?

Cleo . . .

Daddy . . .

You better be on your way to school.

Not exactly.

SIGH.

I start typing another response, but then my phone starts to vibrate with a call.

“I . . . fell on the subway platform,” I say to him instead of hello. It’s a low blow, but I’ll say whatever I need to get him here. “The trains were delayed and my leggings are ripped and it’s snowing, and you know how the snow reminds me of Gigi. I just had an awful morning, okay? Please don’t give me a hard time about this, Daddy. Not today.”

He sighs, long and low. “Cleo, this seriously has to be the last time. If it isn’t, I’ll have to talk to your mother.”

I gasp.“Et tu, Brute?” My dad knows almost everything about Layla, and that I’ve been skipping school to avoid her. But as long as my grades don’t slip, he lets me get away with pretty much whatever I want. My mom’s another story.

“This is the last time, Cleo.”

I’m pretty sure it’s an empty threat, so I grin.

“It will be. I promise. Now, can you meet me?”

“Where are you?” he asks.

He arrives about twenty minutes later. I grabbed a cup of coffee for him, and a tea for me, from the café across the street while I waited, so as soon as I spot him, I run over and push the steaming cup into his gloved hands.

“Oh, honey,” he says as soon as he sees my leggings. He straightens his glasses and pulls me to him. He plants a kiss on my forehead and his bristly goatee tickles my eyebrow. “Why did you want me to meet you here? You should have just come over.”

“I want to build a snowman,” I say, hating that I sound like a five-year-old. “Correction: I need to.”

He makes his Librarian Face--an expression of both confusion and intrigue. He makes this face when he’s cautiously interested in or fascinated by a book, an idea, or a person. I’ve seen him use it with patrons at the library where he works when he’s asked a particularly strange question, and as he reads articles on his tablet in the mornings. Since he moved out a few months ago I’ve seen this face (and him) a lot less, but it’s still so recognizable that I grin at his eggshell-brown skin and dark freckles; his wide, scrunched-up nose. “A snowman,” he says, and it’s a statement and a question all at once.

“Yes,” I say. “I have a theory.”

He purses his lips to stop himself from smiling, and I know what this expression means too: he has no idea what I’m about to say next. “Okay,” he says. He puts his heavy arm over my shoulders. “Tell me.”

We start to walk, strolling past people walking dogs in coats and nannies pushing strollers. Snow is still falling and everything around us feels a little magical and unreal. I inherited my dad’s freckled face, his poor eyesight, and his dreaminess too. He never rushes me to speak because he knows what it’s like to be easily distracted--what it’s like to get lost inside your own head. “I think,” I say, “that I need to make some new memories. I think that if I make enough new ones in the right places, not being friends with Layla anymore will hurt a little bit less.”

My dad sips his coffee. I look across the park at the tall trees and beyond them to where Layla’s walk-up sits beside the bodega, deli, and fire escape, and my breath catches. If I could erase this whole block from the city, I would.

“And these new memories,” Daddy says. “They start with a snowman in this park?”

I nod. “This is where I met her, remember? At that cookout right after Gigi died? But if we do something else in this exact spot, like build a snowman, maybe that will be the first thing I think of when I come here, instead of her.”

“Ah,” he says, something like sadness passing over his features. “I understand.”

We build a snowman. When we’re half done, I throw a few snowballs at my dad and he laughs and dodges them, making his own between searching for stones and sticks to put finishing touches on our creation. As we roll and pat and press the snow into new shapes, I pray that my memories are just as malleable as the snow in my hands. Hopefully my past is as rewritable as I’m pretending it can be.

Ready for Battle

“So you wanna skip school, huh?” my mother says that night, the second she gets home.

I’m brushing my teeth, planning my next new-memory-making trip, when she squeezes into our tiny bathroom behind me.

I’m in pajamas, a satin scarf already wrapped around my head for bed, but she’s still in the tight pencil skirt she wore to the office this morning, her blazer slung over her arm. Her high heels are hanging off the tips of her fingers (she’d never leave her shoes by the door) and there’s barely any space between us at all.

“Oh crap,” I mutter, pressing my thighs closer to the sink. Toothpaste droplets land on the mirror. I don’t know how she found out, but then I remember my father’s threat.

I spit and rinse my mouth out, getting more pissed with him by the second. Some things, like secrets between a father and daughter about said daughter skipping school, are supposed to be sacred. I take my time settling my toothbrush into the cup by the faucet. Not so long ago, it used to have three toothbrushes in it. Now it just has two.

“Did Daddy at least tell you why I skipped?” I ask, slowly turning around.

“No?” Her stormy face turns even stormier. “Your father knew about this?”

“Double crap,” I mumble. “No?” I try.

She rolls her eyes and sits down on the edge of our tub. Her knees bump hard into my shins.

“Jesus, Cleo. I can’t even look at you. And your father . . .”

For a split second, she seems . . . hurt. Like we’ve ganged up on her. Like our life together is a fight and she’s all on her own. But then she’s right back to looking like she’s ready for battle.

“Give me your phone,” she says, holding out a manicured hand. I snatch it from the counter, where it’s innocently playing “Blue in Green” by Miles Davis, and clutch it to my heart.

I slip out of the bathroom and head down the hall, negotiating. “Mom, no! Please? Anything but my phone,” I whine.

“I don’t want to hear it, Cleo.” She follows me to my room, where I reluctantly hand it over. She pockets it and storms out, slamming my door so hard the row of snow globes on my shelves rattle. I flop down on top of my blankets, knowing I’m probably grounded on top of losing the phone. When she yells back to me, “Your father’s picking you up first thing tomorrow. You’ll get the phone back on Monday,” I bolt upright.

“MONDAY?!”

then: July

Evil Genius

“What are you wearing t-t-t-tonight?” Layla asked me.

I stretched out on her pale blue sheets. The window was open and the humidity was punishing. Even the creases behind my knees were sweaty.

“It’s so hot,” I said. “What can I wear to be as close to completely naked as possible?” Layla laughed as she pulled on a long, thin-fabricked dress, its pale pink color delicate and pretty against her sun-kissed brown skin. She lifted her dark wavy hair from where it was tucked against her back, then shimmied her little “new dress” shimmy. Her reflection winked at me in her full-length mirror. “I’m sure mmmost of the guys, and a few of the girls, w-would freaking love that,” she said, raising her thick eyebrows.

I rolled my eyes, because dating was the last thing on my mind. I was mostly just nervous to be going to my first big high school party. As rising sophomores, Layla and I had been invited to a grand total of two, and I’d skipped the first one earlier that summer because my dad had gotten us tickets to Shakespeare in the Park. I was only going to this one because Layla was making me, and because Valeria’s building had rooftop access that would provide an excellent view of the fireworks.

“You have a dress like this, right?” she asked a few minutes later, holding out a thin black thing in my direction. I took the wisp of clothing in my hands, rubbing the smooth fabric between my fingers.

“You own something in black?” I asked, teasing her because black was my signature color, and the majority of her clothes were as light as the walls of her bedroom--lavender and seafoam, shades of powdery pink, pale yellows, and sky blues.

“Shut up,” she said. “D-don’t you?” I nodded, though the dress that hung in my closet wasn’t nearly as delicate.

“So you should wear it tonight. . . .” Her mouth was still open, so I knew the sentence wasn’t finished. Sometimes, Layla’s stutter caused her to get blocked so badly that words got stuck in her throat and no sound came out at all. I waited.

She closed her mouth, cleared her throat, walked over to her dresser, and tried again. “W-with these.” She pulled out a pair of shiny gold hoop earrings. “And you should p-put in your c-c-contacts. Oh! And let me do eyeliner. You have great eyes, C-Cleo.” I always hated that my name began with one of the hardest consonants for her to pronounce.

I stepped up to her mirror, holding the dress in front of me. I took my glasses off and stepped even closer to my reflection so I could see my face more clearly. Will anyone even notice my “great eyes” with all these freckles? What does having “great eyes” even mean? But Layla knew about this stuff in a way I didn’t. She’d cared deeply about aesthetics for as long as I’d known her, and she’s been wearing at least a little makeup since the first time her older sister showed her how to use a mascara wand when we were still in middle school.

I pulled Layla’s dress on and it was way too tight. I had curves in every place she didn’t, but she refused to acknowledge that we were completely different sizes.

“I like, don’t know how to party,” I said, immediately taking the dress off. “Do you think people will be drinking?”

Layla pulled off the pink dress she was wearing and slipped into a yellow one before wrapping me in a hug. Her voice was soft and raspy and her hair and skin smelled like sandalwood. She pulled back and looked at me.

“Cleo. Obviously there will b-b-be drinking. That d-doesn’t mean you have to drink. I’m not g-going to. And if some d-douche tries to make me or you, I’ll k-k-kick him in the balls.”

I laughed. It made sense that she smelled like a forest and sounded like the beginning of a wildfire. She had a temper, and once it was lit, the girl could burn.

To take my mind off the party, off the way Layla wanted me to look and who all might be there drinking, I said, “So I got this email from Novak today.”

Layla looked at me and cringed. “Why is a t-teacher emailing you in the summer?”

I grinned and flopped back down on her bed. “She’s spending part of the summer at the Globe Theatre in London,” I said a little dreamily. I’d been obsessed with everything about London since I was twelve--the tea, the culture, the landmarks--and Layla knew this. My London snow globe was the most prized one in my collection.