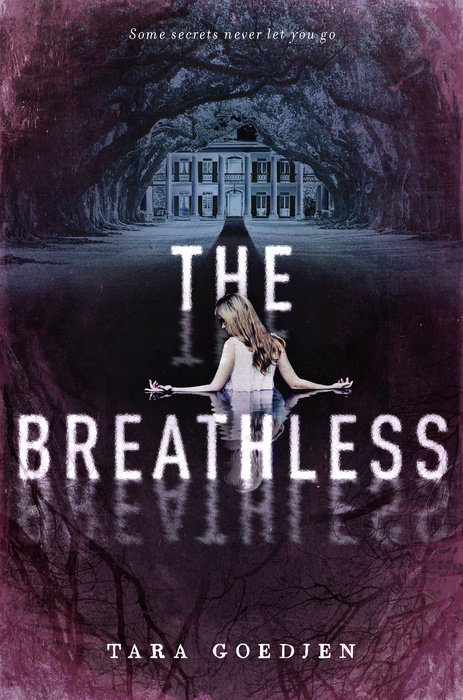

The Breathless

Author Tara Goedjen

For fans of the dark family secrets of We Were Liars and the page-turning suspense of The Unbecoming of Mara Dyer, The Breathless is a haunting tale of deeply buried secrets, forbidden love, and how far some will go to bring back what’s long dead.

No one knows what really happened on the beach where Roxanne Cole’s body was found, but her boyfriend, Cage, took off that night and hasn’t been seen since.

For fans of the dark family secrets of We Were Liars and the page-turning suspense of The Unbecoming of Mara Dyer, The Breathless is a haunting tale of deeply buried secrets, forbidden love, and how far some will go to bring back what’s long dead.

No one knows what really happened on the beach where Roxanne Cole’s body was found, but her boyfriend, Cage, took off that night and hasn’t been seen since. Until now. One year—almost to the day—from Ro’s death, when he knocks on the door of Blue Gate Manor and asks where she is.

Cage has no memory of the past twelve months. According to him, Ro was alive only the day before. Ro’s sister Mae wouldn’t believe him, except that something’s not right. Nothing’s been right in the house since Ro died.

And then Mae finds the little green book. The one hidden in Ro’s room. It’s filled with secrets—dangerous secrets—about her family, and about Ro. And if what it says is true, then maybe, just maybe, Ro isn’t lost forever.

And maybe there are secrets so dark, they should never see the light of day.

“[The Breathless] is full of secrets, dark magic, and satisfying twists and turns.”—Booklist

“Bringing together horror, romance, and tragedy in one creepy old house,…[The Breathless] will leave readers heartbroken and haunted.”—The Bulletin

“An absorbing and romantic Gothic mystery that will haunt you long after the final page.”—Kara Thomas, author of The Darkest Corners and Little Monsters

“Evocative and mysterious; The Breathless is rich with layered secrets and intertwined stories of love and loss.”—Sarah Tomp, author of My Best Everything.

“The Breathless is part magic-tinged mystery, part Southern Gothic, and part romance that chills and thrills you all at once. I couldn't put it down!”—Tara Hudson, author of the Hereafter trilogy

“This sultry Southern tale is drenched in atmosphere! A world of secrets, mysterious family heirlooms, and forbidden love. Get ready to be bewitched by a story where not only does the past live on . . . the dead do, too!”—Adriana Mather, New York Times bestselling author of How to Hang a Witch

An Excerpt fromThe Breathless

Chapter 1

Steam settled over the bathroom mirror. In the candlelight, Mae traced a name on the glass. The more she stared at it, the sicker she felt. When she couldn’t take it anymore, she stepped out of the pile of wet clothes at her feet and eased into the hot bath. A flush shot through her body, all the way to her toes, and she watched the paint streaks running from her hands in faint trails of color.

Mae thought of her sister and shut her eyes, trying to block out everything else. Small waves sloshed against the cracked sides of the tub, and she turned on the faucet so it was dripping, making ripples. There was a slight lift underneath her, that feeling of being raised by the water. She’d read once that you could rid yourself of pain by pretending you were floating outside your body. Or you could breathe into it, make yourself feel the edges of the pain, try to find the end of it.

Inhale, exhale. Inhale. Mae dunked her head and…

Chapter 1

Steam settled over the bathroom mirror. In the candlelight, Mae traced a name on the glass. The more she stared at it, the sicker she felt. When she couldn’t take it anymore, she stepped out of the pile of wet clothes at her feet and eased into the hot bath. A flush shot through her body, all the way to her toes, and she watched the paint streaks running from her hands in faint trails of color.

Mae thought of her sister and shut her eyes, trying to block out everything else. Small waves sloshed against the cracked sides of the tub, and she turned on the faucet so it was dripping, making ripples. There was a slight lift underneath her, that feeling of being raised by the water. She’d read once that you could rid yourself of pain by pretending you were floating outside your body. Or you could breathe into it, make yourself feel the edges of the pain, try to find the end of it.

Inhale, exhale. Inhale. Mae dunked her head and held herself down, needing to know what her sister had felt. She opened her eyes under the water and looked at the dark ceiling, at her hair floating out in wavy strands. Then over at the foggy mirror, the melting white candles by the sink, the rusting tub. That waterline above her—the surface so close with the promise of air. Her lungs were burning, but she forced herself to stay under, staring at the line of water like a horizon, her chest hot and tight. Ro was found on the shore, the tide at her legs. Her head bloody, with no other sign of struggle. Ro dead and everyone blaming Cage Shaw.

When her lungs were about to burst, Mae finally shot up for air, gulping it in. It was hard to drown yourself, maybe impossible, unless there was something or someone holding you down.

She took in deep breaths as water coursed over her eyes. It was like being outside earlier that day, when she’d tried to capture the rainstorm on canvas. Painting was the one thing that helped her forget. Now that it was summer and school was out, she couldn’t rely on the noise and bodies of the other kids to crowd out the dark thoughts, so she painted instead, kept her hands moving. If she had more friends it might help, but she didn’t want to answer questions about Ro, or go to parties with Elle and drink until she forgot. So today she’d set up her easel on the porch while the rain had poured from the sky, loud enough to water down her thoughts into colors.

The other way to get rid of pain was to shove it behind a door in your mind and hope it didn’t leak out. Mae had assigned a door for all the memories that hurt. Black was the color of Ro’s door. Her mother’s was pale yellow. A red door held back her dad’s anger. And her granddad’s was white, the color of the milk and brandy she took to him when he couldn’t sleep and couldn’t find the words to ask for it. All the doors had faded to the back of her mind—all except for Ro’s.

The black door usually kept the memories from seeping through, which was a good thing. You could wish a thousand times that something hadn’t happened, but you couldn’t undo it. You couldn’t feel sorry for yourself either, because then you’d just rot, starting with your heart. Mae wasn’t going to rot. She would paint until her fingers fell off before she did that. She’d keep the doors shut tight.

She held out her hands. Her fingertips were starting to wrinkle, but at least the paint was gone. The bathwater was warm against her skin, her knees were sticking up like two little islands in the flickering candlelight. A breeze was coming from the bathroom window, leaking through the cracked glass pane, and outside everything was dripping. Her lids went heavier and heavier. Things would get better; maybe all it took was time. . . .

A noise startled her upright.

Mae gasped because the bath was cold, like ice. The room was dark now. Every candle had burned down to a pool of wax. She must have fallen asleep. It was so cold in the water, colder than the air.

A faint glow of moonlight was coming from the window, and the rain had stopped. All the fog was gone from the mirror but somehow Roxanne was still there, in thin smears across the glass. The name looked strange now; it didn’t look like her handwriting at all.

Mae got out and wrapped a towel around herself, drying off over the uneven tiles. In the mirror was a shadow: long hair, dark eyes. She was going to smile more this year—she was going to try harder, like Ro would have wanted.

As she got dressed, she heard someone singing in the hallway. Maybe Elle was still awake? She yanked her shirt over her wet hair and then pulled on her sister’s red sweatshirt, thin with a zip up the front, the one she hadn’t washed since it happened. She breathed in the scent—cloves and mint—then stepped out of the bathroom.

Elle’s room was quiet and dark, and so was Sonny’s. Mae heard the sound again, now more of a whisper. Probably just Elle talking on the phone, but something felt off. Her heart started thudding as she moved deeper into the shadows, passing the long railing that overlooked the foyer and the old chandelier that trembled with her steps.

The humming—it seemed more like humming than whispering—grew louder the farther she walked over the cold floorboards. Prickles raced across her skin when she got to the end of the hallway. The noise was coming from Ro’s room.

Mae’s heart quickened. She leaned toward the door, listening.

Nothing. There was nothing, because no one went into this room anymore. But she had heard . . . what? There was only silence now on the other side of the wood.

She wasn’t supposed to go in—her dad’s rule. She touched the brass handle, then opened the door and fumbled for the light switch.

Overhead, the bulb flared bright and burned out. She blinked in the dark, her fist tightening around the handle.

“Who’s there?”

Moonlight was shining through the curtained window, casting shadows.

“Elle?” she whispered. Then, because she couldn’t help herself: “Ro?”

She wasn’t getting enough air; she really might faint. The room was dark, empty. She had expected to see her twin, or even her granddad, but there was no one. Just the shapes of furniture no longer used. Piles of clothes that hadn’t been worn in almost a year, books that hadn’t been opened.

Then she whirled. A soft tapping noise was coming from the wardrobe. In the murky haze she could see its door was ajar.

Mae forced herself to step all the way into the bedroom. The tapping was louder—it sounded like her granddad’s cane striking wood, tap thud, tap thud, tap. It was coming from the side of the wardrobe, behind its open door.

She took a step closer, willing her heart to stop beating so hard. In front of the wardrobe she hesitated, and then she pulled the door back.

Ro’s jewelry box was on the ground, overturned. Its gears were whirring and stopping, whirring and stopping. Mae stared at it, relief making her legs go watery. On top of the lid, the delicate ballerina twitched, hitting the floor over and over. One of its ceramic legs had broken off, but the rest of it was intact, its arms clasped together like a halo as it shuddered.

Her dad wanted this room kept exactly how it was—he needed it that way. She scooped up the jewelry that had spilled: dangly feather earrings, threaded shell bracelets, a gold locket, the sand dollars Ro had kept for good luck. Her sister’s wide bangles were scattered across the floor, and she gathered them up one by one, then found a ring by the bookshelf.

Strange—a ring she’d never seen before. She picked it up and held it in the moonlight. It was a gold band studded with tear-shaped rubies. It looked like an antique. The black door in her mind creaked open, and it came to her. This was the ring Ro had been wearing that last day. Elle must have rescued it, stored it away in the jewelry box.

Mae turned it over in her hand and then slid it onto her finger. It was too big, so she took it off, slipped it into the jewelry box, and put the box back on the wardrobe.

As she turned to leave, the curtains billowed out. A breeze swept through the room, and Ro’s sketches on the wall fluttered. Mae tensed on instinct and then almost laughed aloud. The old windows in the house opened outward and sometimes rattled loose in the wind. That’s what she must have heard earlier in the hallway: the window blowing open. Some animal, probably a squirrel, had gotten in and tipped the jewelry box off the wardrobe.

She closed the latch and turned to go again, but as she stepped around the edge of the mattress she kicked something sharp. It skidded across the floor and under the bed. Another piece of jewelry? She crouched down to grab it and froze, her hand outstretched.

Lying beneath the bed was a leather book.

Mae stared at it a moment and then pulled it out, a knot tightening in her stomach. Just as she started to open it, a floorboard creaked in the hallway. She shoved the small book into her sweatshirt pocket and hurried out of the room, closing the door behind her as softly as she could. One side of her sweatshirt was heavy now, dragged down by the weight in her pocket. She’d made it halfway through the hallway and had almost reached her own room when—

“Mae?”

She spun around, startled. Her dad was standing in the dark with a glass in his hand. “Thought I was the only one awake.”

“Me too,” she said, her voice coming out strained. But he hadn’t seen her in Ro’s bedroom—he wouldn’t be this calm.

Sonny held up his drink. “Nightcap.” He was in jeans and a T-shirt, like he hadn’t gone to sleep yet and wasn’t planning to. He turned, and Mae thought that was the end of it, but he waved her on. “Come downstairs.”

“I—” Mae started, but her dad cut her off.

“Come on, you need a glass of milk,” he said. “It’ll help you sleep.”

She nodded. It was clear she had no choice but to have the milk, but she didn’t know what to expect. Sonny mostly kept to himself; a conversation alone with him was new territory.

Mae followed him down the curving staircase, the book heavy in her pocket, as if aching to be read. He flipped on the light in the kitchen and she blinked at the brightness. It hit the windows and the French doors that opened into the overrun garden. Light streamed over the stone cherub by the roses and the pink lantanas and trickled onto the high green hedge. Everything was still glistening from the rain.

Sonny grabbed a saucepan and poured milk into it. “Trick is,” he said, “can’t heat it up too long or it makes that sticky layer on top.”

“That’s the milk skin,” Mae murmured. “It’s from the protein, Dad.”

He shot her a glance and then switched off the stove, his long ponytail swaying across his back. He always told them to use his first name, though he never said why. Maybe that was less painful, since there was no one to call Mom.

“Try it.” He tipped the milk into a mug and set it on the table next to his glass of whiskey. His chair groaned as he lowered himself into it. “When I was a kid, your grandpa would heat up milk when I was scared and couldn’t sleep.”

“He did?” Mae stilled—it felt like if she moved her dad would stop talking. Sonny never talked about when he was young. He never talked much to anyone, though neither did she. “What else did he do?” she pressed.

He held his whiskey, seemed to think a moment. “I’d get nightmares. Blue Gate seemed so old, even back then. Your grandpa would read me stories about magic. Said it could protect me.” His face broke into a smile the way it hadn’t in a long time.

Mae’s hands flexed—she wanted to draw him like this. She edged into the seat beside him, cupped her palms around the warm milk. “And then what happened?”

He swirled the whiskey, the scent sharp and heady. “And then I grew up, Mae, and I told him he was full of shit.”

She winced. Her granddad didn’t stand a chance against Sonny. He took a sip of his drink and looked at her. “I found the back door open today.”

“Oh.” Her heart dropped; the milk was just a trap. He’d only sat her down for another lecture. Why had she thought this was somehow different? “I’ll make sure it’s locked next time.” It shouldn’t have been open; both she and Elle were so careful.

Sonny let out a sigh, scratched at his hair. “You girls think I’m too hard on you.”

He didn’t know the half of it. Didn’t know how she tiptoed around the house, waiting for him to turn like when the sky darkens with a sudden storm.

“I only want to keep you safe,” he said.

“I know.” She tilted the mug to drink so she wouldn’t have to say anything more. Elle knew how to push until he snapped, and sometimes she knew right where to stop, but Mae didn’t like that in-between ground where anything she said could be taken the wrong way. Instead, whenever she felt like yelling at him, she shoved all her anger through the bright red door in her mind and slammed it shut.

“I think he might come back one of these days,” Sonny went on, “and when he does, I’ll be ready.”

Mae coughed, choking on the milk. She knew exactly who he was talking about. She set her mug down hard, but her dad didn’t seem to notice. “How do you . . .” She cleared her throat. “Why do you think he did it?”

Sonny shrugged, his eyes going dark. “He was always dwelling on her.”

She straightened in her seat, grasped her mug tighter. Arguing with him wouldn’t help, and neither would talking about Ro. Every time she said Ro’s name it was like she’d hit him, and Sonny didn’t like getting hit.

“Dad . . .” She forced herself to speak. “Whatever happened, it’s not your fault.”

It’s not anyone’s fault, she wanted to add, but she didn’t know that for sure. No one did. Not yet. She shoved her hands into her pockets, felt the edge of the book she’d taken.

“You’re a good kid, Mae,” he said, but he didn’t look at her, just swirled his glass of whiskey. “You know, with fishing, there’s a lot of time to think, sometimes too much. It can pull you down in the bad thoughts, if you’re not careful.”

That must be why he’d quit. Why he hadn’t worked since Ro died. She took a sip of the milk, held it on her tongue. She didn’t know how to make him feel better, so she said what she’d been wanting to hear. “It’s going to be okay.”

He shook his head, his shoulders tight. “I just don’t know, Mae.” She caught the sharp scent of his drink as he lifted the glass. “Maybe one day you’ll understand what it’s like to be a father.”

“No,” she said. “I don’t think I’ll ever understand what it’s like to be a father.”

Sonny looked at her and for a moment it seemed he might smile again, like she’d said the right thing. Instead he sighed. “You should be asleep.” He stood, drained his whiskey. “I’m headed that way myself.”

At the doorway he stopped, and she saw that his pistol was tucked into the back of his jeans—he’d been carrying it around since it happened. Her stomach twisted.

“I count myself lucky to be your dad, Mae Eliza.” He was turned from her, already walking off, so she could hardly hear him. “Must have done something right, huh?”

Her eyes watered and she felt a knot in her throat. She didn’t know whether she was happy he’d said it or sad because she’d never live up to Ro. Ro had been his favorite and with her gone, he was just going through the motions.

Mae stayed at the table, listening to the floorboards creak as he went upstairs. She was tired of worrying about him, tired of not being able to say her sister’s name aloud, and she didn’t know how much longer they could last without answers.

She waited until she heard his door close and then pulled the book from her pocket. In the light of the empty kitchen its leather looked greenish and old. It was small, the size of her hands held together side to side, but it was thick and tied shut with a ribbon. The back cover was missing, torn off completely, but the front cover was etched with two dark coffins.

It was her sister’s green book. The one Ro had found in the house and swore was a secret, the first and only time she’d shown Mae.

And here it was again.

Mae weighed it in her palms. It felt heavy, its leather almost warm. A gritty resolve settled in her stomach, and for the first time in nearly a year she didn’t feel so aimless—she knew what she had to do. When she stood to turn off the light, she could feel Ro beside her, whispering with her red velvet breath, Open it, Mae, open it.