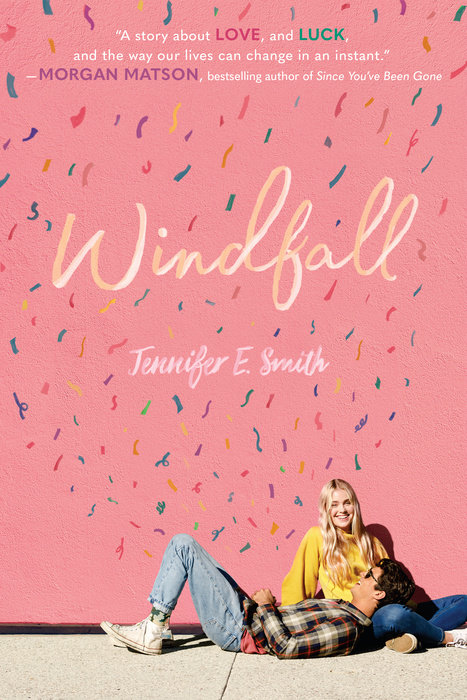

Windfall

Author Jennifer E. Smith

This romantic story of hope, chance, and change from the author of The Statistical Probability of Love at First Sight is one JENNY HAN says is filled with all of her "favorite things," MORGAN MATSON calls “something wonderful” and STEPHANIE PERKINS says “is rich with the intensity of real love.”

Alice has never believed in luck, but that doesn’t stop her from rooting for love. After pining for her best friend Teddy for years, she jokingly…

This romantic story of hope, chance, and change from the author of The Statistical Probability of Love at First Sight is one JENNY HAN says is filled with all of her "favorite things," MORGAN MATSON calls “something wonderful” and STEPHANIE PERKINS says “is rich with the intensity of real love.”

Alice has never believed in luck, but that doesn’t stop her from rooting for love. After pining for her best friend Teddy for years, she jokingly gifts him a lottery ticket—attached to a note professing her love—on his birthday. Then, the unthinkable happens: he actually wins.

At first, it seems like the luckiest thing on earth. But as Teddy gets swept up by his $140 million windfall and fame and fortune come between them, Alice is forced to consider whether her stroke of good fortune might have been anything but.

She bought a winning lottery ticket. He collected the cash. Will they realize that true love’s the real prize?

Featured in Seventeen Magazine's "What's Hot Now"

“Windfall is about all of my favorite things—a girl’s first big love, her first big loss, and—her first big luck.”

—JENNY HAN, New York Times bestselling author of To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before

“Windfall is perfectly named; reading it, I felt like I had suddenly found something wonderful.”

—MORGAN MATSON, New York Times bestselling author of The Unexpected Everything

“Windfall is rich with the intensity of real love— in all its heartache and hope.”

—STEPHANIE PERKINS, New York Times bestselling author of Isla and the Happily Ever After

"If you’re looking for your next great read, then you’re in 'luck!'" —Justine Magazine

An Excerpt fromWindfall

One

When the man behind the counter asks for my lucky number, I hesitate.

“You must have one,” he says, his pen hovering over the rows of bubbles on the form. “Everyone does.”

But the problem is this: I don’t believe in luck.

At least not the good kind.

“Or it could be anything, really,” he says, leaning forward on the counter. “I just need five numbers. And here’s the trick. The big secret. You ready?”

I nod, trying to look like I do this all the time, like I didn’t just turn eighteen a few weeks ago, like this isn’t my first time buying a lottery ticket.

“You have to make them really, really good ones.”

“Okay then,” I say with a smile, surprised to find myself playing along. I planned to let the computer decide, to put my faith in randomness. But now a number floats to the surface with such ease that I offer it up to him before thinking better of it. “How about thirty-one?”

Teddy’s birthday.

“Thirty-one,” the man repeats as he scratches out the corresponding bubble. “Very promising.”

“And eight,”…

One

When the man behind the counter asks for my lucky number, I hesitate.

“You must have one,” he says, his pen hovering over the rows of bubbles on the form. “Everyone does.”

But the problem is this: I don’t believe in luck.

At least not the good kind.

“Or it could be anything, really,” he says, leaning forward on the counter. “I just need five numbers. And here’s the trick. The big secret. You ready?”

I nod, trying to look like I do this all the time, like I didn’t just turn eighteen a few weeks ago, like this isn’t my first time buying a lottery ticket.

“You have to make them really, really good ones.”

“Okay then,” I say with a smile, surprised to find myself playing along. I planned to let the computer decide, to put my faith in randomness. But now a number floats to the surface with such ease that I offer it up to him before thinking better of it. “How about thirty-one?”

Teddy’s birthday.

“Thirty-one,” the man repeats as he scratches out the corresponding bubble. “Very promising.”

“And eight,” I tell him.

My birthday.

Behind me, there’s a line of people waiting to buy their own tickets, and I can practically feel their collective impatience. I glance up at the sign above the counter, where three numbers are glowing a bright red.

“Three-eighty-two,” I say, pointing at the display. “Is that millions?”

The man nods and my mouth falls open.

“That’s how much you can win?”

“You can’t win anything,” he points out, “unless you pick some more numbers.”

“Right,” I say with a nod. “Twenty-four, then.”

Teddy’s basketball number.

“And eleven.”

His apartment number.

“And nine.”

The number of years we’ve been friends.

“Great,” says the man. “And the Powerball?”

“What?”

“You need to pick a Powerball number.”

I frown at him. “You said five before.”

“Yeah, five plus the Powerball.”

The sign above the counter clicks forward: 383. It’s an amount nearly too big to mean anything--an impossible, improbable figure.

I take a deep breath, trying to shuffle through the numbers in my head. But only one keeps appearing again and again, like some kind of awful magic trick.

“Thirteen,” I say, half-expecting something to happen. In my mind the word is full of voltage, white-hot and charged. But out loud it sounds like any other, and the man only glances up at me with a doubtful look.

“Really?” he asks. “But that’s unlucky.”

“It’s just a number,” I say, even though I know that’s not true, even though I don’t believe it one bit. What I know is this: numbers are shifty things. They rarely tell the whole story.

Still, when he hands over the slip of paper--that small square of illogical math and pure possibility--I tuck it carefully into the pocket of my coat.

Just in case.

Two

Outside, Leo is waiting. It’s started to snow, the flakes heavy and wet, and they settle thickly over his dark hair and the shoulders of his jacket.

“All set?” he asks, already starting to walk in the direction of the bus stop. I hurry after him, skidding a little in the fresh snow.

“Do you have any idea how much this ticket could be worth?” I say, still trying to get my head around the number.

Leo raises his eyebrows. “A million?”

“No.”

“Two?”

“Three hundred and eighty-three million,” I tell him, then add, in case it isn’t entirely clear: “Dollars.”

“That’s only if you win,” he says, grinning. “Most people get nothing but a piece of paper.”

I feel for the ticket in my pocket. “Still,” I say, as we arrive at the three-sided shelter of the bus stop. “It’s kind of crazy, isn’t it?”

We sit down on the bench, our breath making clouds that hang in the air before disappearing. The snow has a sting to it, and the wind off the lake is icy and sharp. We scoot closer together for warmth. Leo is my cousin, but really he feels more like my brother. I’ve been living with his family ever since I was nine, after my parents died a little more than a year apart.

In the hazy aftermath of that horrible time, I found myself plucked out of San Francisco--the only home I’d ever known--and set down halfway across the country with my aunt and uncle in Chicago. Leo was the one to save me. When I arrived I was still reeling, stunned by the unfairness of a world that would take away my parents one at a time with such coldhearted precision. But Leo had decided it was his job to look out for me, and it was one he took seriously, even at nine.

We were an odd pair. I was wispy and pale, with hair like my mother’s, so blond it took on a slightly pinkish hue in certain light. Leo, on the other hand, had inherited his liquid brown eyes and messy thatch of dark hair from his own mom. He was funny and kind and endlessly patient, whereas I was quiet and heartsick and a little withdrawn.

But right from the start, we were a team: Leo and Alice.

And, of course, Teddy. From the moment I arrived, the two of them--inseparable since they were little--took me under their wing, and we’ve been a trio ever since.

When the bus appears, its headlights hazy in the whirling snow, we climb on. I slide into a seat beside the window, and Leo sinks down next to me with his long legs stretched into the empty aisle, a puddle already forming around his wet boots. I reach into my bag for the birthday card I bought for Teddy, then hold out a hand, and without even needing to ask, Leo passes over the heavy fountain pen he always carries with him.

“So I ended up stealing your idea,” he says, pulling a pack of cigarettes from his coat pocket. He twirls them between his fingers, looking pleased with himself. “Another perk of turning eighteen. I know he doesn’t smoke, but I figure it’s still better than the IOU for a hug he gave me.”

“You got a hug?” I say, looking over at him. “I got one for a free ice cream, which I somehow ended up paying for anyway.”

Leo laughs. “Sounds about right.”

I pin the card against the seat in front of me, trying to keep it steady against the bouncing of the bus. But as I stare at the blank interior, my heart starts to hammer in my chest. Leo notices me hesitate and shifts in his seat, angling himself toward the aisle to give me some privacy. I stare at his back for a second, wondering whether he’s just being polite or whether he’s finally guessed my secret, a thought that makes my face burn.

For almost three years now, I’ve been in love with Teddy McAvoy.

And though I’m painfully aware that I probably haven’t been hiding it very well, I usually choose--in the interest of self-preservation--to believe that’s not the case. The one consolation is that I’m pretty sure Teddy has no idea. There’s a lot to love about him, but his powers of observation are questionable at best. Which is a relief in this particular situation.

It took me by surprise, falling in love with Teddy. For so many years, he’d been my best friend: my funny, charming, infuriating, often idiotic best friend.

Then one day, everything changed.

It was spring of freshman year, and we were on a hot dog crawl, of all things, a walking tour that Teddy had mapped out to hit all the best spots on the North Side. The morning had started off cool, but as the day wore on it became too warm for my sweatshirt, which I tied around my waist. It wasn’t until our fourth stop--where we sat at a picnic table, struggling to finish our hot dogs--that I realized it must have fallen off along the way.

“Wasn’t it your mom’s?” Leo asked, looking stricken, and I nodded. It was just an old Stanford hoodie with holes in both cuffs. But the fact that it had belonged to my mother made it priceless.

“We’ll find it,” Teddy promised as we began retracing our steps, but I wasn’t so sure, and my chest ached at the thought of losing it. By the time it started to pour we’d only made it halfway back through the day’s route, and it was quickly becoming clear that the sweatshirt was a lost cause. There was nothing to do but give up on it.

But later that night my phone lit up with a text from Teddy: I’m outside. I crept downstairs in my pajamas, and when I opened the front door, he was standing there in the rain, his hair dripping and his jacket soaked, holding the wet sweatshirt under his arm like a football. I couldn’t believe he’d found it. I couldn’t believe he’d gone back for it.

Before he could say anything, I threw my arms around him, hugging him tight, and as I did I felt something crackle to life inside me, like my heart was a radio that had been full of static for years, and now, all at once, it had gone suddenly clear.

Maybe I’d loved him long before then. Maybe I just hadn’t realized it until I opened the door that night. Or maybe it was always meant to happen this way, with a shivering boy holding a damp sweatshirt on my front stoop, the whole thing as inevitable as day turning to night and back to day again.

It hasn’t been easy, loving him; it’s like a dull throb, constant and persistent as a toothache, and there’s no real cure for it. For three years I’ve acted like his buddy. I’ve watched him fall for a string of other girls. And all this time, I’ve been too afraid to tell him the truth.

I blink at the card in front of me, then jiggle the pen in my hand. Out the window the night is cloaked in white, and the bus carried us farther from the heart of the city. Something about the darkness, all those flecks of snow hurrying to meet the windshield, dizzying and surreal, makes me feel momentarily brave.

I take a deep breath and write: Dear Teddy.

Then, before I can second-guess myself, I keep going, my pen moving fast across the page, a quick, heedless emptying of my heart, an act so reckless, so bold, so monumentally stupid that it makes my blood pound in my ears.

When I’m finished I reach for the envelope.

“Don’t forget the ticket,” Leo says, and I slip it out of my pocket. It’s now bent, and one of the corners has a small tear, but I lay it flat against my leg and do my best to straighten it out. As Leo leans in to get a better look, I feel my face flush all over again.

“Teddy’s birthday?” he says, peering at the numbers, his glasses fogged from the warmth of the bus. “Kind of an obvious one . . .”

“It seemed appropriate for the occasion.”

“Your birthday. Teddy’s basketball jersey.” He pauses. “What’s eleven?”

“A prime number.”

“Very funny,” he says, then his eyes flash with recognition. “Oh, right. His apartment. And nine?”

“The number of years--”

“That you guys have been friends, right,” he says, then turns to the final number. I watch his face as it registers--that awful, conspicuous thirteen--and he snaps his chin up, his dark eyes alert and full of concern.

“It doesn’t mean anything,” I say quickly, flipping the ticket over and pressing it flat with my hand. “I had to think fast. I just . . .”

“You don’t have to explain.”

I shrug. “I know.”

“I get it,” he says, and I know that he does.

That’s the best thing about Leo.

He watches me for a second longer, as if to make sure I’m really okay; then he sits back in his seat so that we’re both facing forward, our eyes straight ahead as the bus hurtles through the snow, which is thick as static against the windshield. After a moment, he reaches over and places a hand on top of mine, and I lean against him, resting my head on his shoulder, and we ride like that the rest of the way.

Three

The inside of Teddy’s apartment is warm and almost humid, the small space filled with too many bodies and too much noise. Beside the door, the old-fashioned radiator is hissing and clanging, and from the bedroom the music thumps through the walls, making Teddy’s school photos tremble in their frames. The single window by the galley kitchen is already fogged over, and someone has written TEDDY MCAVOY IS A across it, the last word rubbed out so that it’s impossible to tell just what exactly he is.

I stand on my tiptoes, scanning the room.

“I don’t see him,” I say, shrugging off my coat and throwing it on top of the haphazard pile that’s sprung up on the floor. Leo picks it up, knotting one of his sleeves to one of mine so that our jackets look like they’re holding hands.

“I can’t believe he’s doing this,” he says. “His mom is gonna kill him.”

But there’s more to it than that. There’s a reason Teddy doesn’t usually have people over, even though his mom works nights as a nurse. Their whole apartment is only two rooms--three if you count the bathroom. The kitchen is basically just a small tiled area tucked off in the corner, and Teddy has the only bedroom. His mom sleeps on the pullout couch while he’s at school, a detail that makes it glaringly obvious they don’t have the same kind of money as most of our classmates.

But I’ve always loved it here. After Teddy’s dad walked out on them, they had to give up their spacious two-bedroom apartment in Lincoln Park, and this was all they could afford. Katherine McAvoy did what she could to make it feel like home, painting the main room a blue so bright it feels like being in a swimming pool, and the bathroom a cheerful pink. In Teddy’s room each wall is a different color: red, yellow, green, and blue, like the inside of a parachute.

Tonight, though, it feels less cozy than crowded, and as a cluster of junior girls walk past us I hear one of them say, her voice incredulous, “It’s only a one-bedroom?”

“Can you imagine?” says another, her eyes wide. “Where does his mom sleep?”

“I knew he wasn’t rich, but I didn’t realize he was, like, poor.”

Beside me I can feel Leo bristle. This is exactly why Teddy never has anyone but us over. And why it’s so strange to see dozens of our classmates crammed into every available inch of space tonight. On the couch, five girls are wedged together so closely it’s hard to imagine how they’ll ever get up, and the hallway that leads to Teddy’s room is clogged by the better part of the basketball team. As we stand there, one of them comes barreling past us--his cup held high, the liquid sloshing onto his shirt--shouting, “Dude! Dude! Dude!” over and over as he elbows his way toward the kitchen.